La Haine

La Haine (French pronunciation: [la ɛn], lit. "Hate") is a 1995 French black-and-white drama film written, co-edited, and directed by Mathieu Kassovitz. It is commonly released under its French title "La Haine", although its U.S. VHS release was titled Hate. It is about three young friends and their struggle to live in the banlieues of Paris. The title derives from a line spoken by one of them, Hubert, "La haine attire la haine!", "hatred breeds hatred".

| La Haine | |

|---|---|

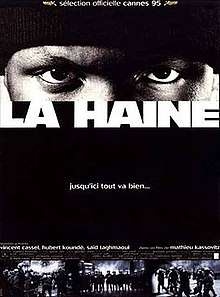

La Haine cover, with the tagline Jusqu'ici tout va bien... ("So far, so good…") | |

| Directed by | Mathieu Kassovitz |

| Produced by | Christophe Rossignon |

| Written by | Mathieu Kassovitz |

| Starring | Vincent Cassel Hubert Koundé Saïd Taghmaoui |

| Music by | Assassin |

| Cinematography | Pierre Aïm |

| Edited by | Mathieu Kassovitz Scott Stevenson |

| Distributed by | Canal+ |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $2.6 million[1] |

| Box office | $15.3 million[2] |

Plot

La Haine opens with news footage of urban riots in a banlieue in the commune of Chanteloup-les-Vignes near Paris, caused by the attack and hospitalization of Abdel Ichacha, leading to an attack on the police station and a riot police officer losing his revolver. The film depicts approximately twenty consecutive hours in the lives of three friends of Abdel, all young men from immigrant families, living in the aftermath of the riot.

Vinz is a young Jewish man with an aggressive temperament who wishes to avenge Abdel, has a blanket condemnation of all police officers, and secretly reenacts Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver in the bathroom mirror. Hubert is an Afro-French boxer and small-time drug dealer who only thinks of leaving the city for a better life and refuses to provoke the police, but whose boxing gymnasium was burned down in the riots. Saïd is a young North African Muslim who plays a mediating role between Vinz and Hubert.

The three go through an aimless daily routine, frequently finding themselves under police scrutiny. After the police break a rooftop gathering and the three sit idly on a playground, Vinz reveals to the other two that he has found the .44 Magnum revolver lost in the riot, and plans to use it to kill a police officer if Abdel dies. Although Hubert disapproves, Vinz secretly takes the gun with him. The three go to see Abdel in the hospital, but are turned away by the police. Saïd is arrested after their aggressive refusal to leave.

The group narrowly escapes after Vinz nearly shoots a riot officer. They take a train to Paris, where their responses to both benign and malicious Parisians cause several situations to escalate to dangerous hostility. In a public restroom, a Gulag survivor tells them of a friend who refused to relieve himself in public and subsequently froze to death, puzzling the three as to the meaning of the story.

They then go to see Asterix, an avid cocaine user who owes Saïd money, leading to a violent confrontation as he appears to try to force Vinz to play Russian roulette (the gun is secretly unloaded). A run-in with sadistic plainclothes police, who verbally and physically abuse Saïd and Hubert, results in the three missing the last train from Saint-Lazare station and spending the night on the streets.

After being kicked out of an art gallery and unsuccessfully trying to hotwire a car, the trio stay in a shopping mall and learn from a news broadcast that Abdel is dead. They travel to a roof-top from which they insult skinheads and policemen, before encountering the same group of skinheads who begin to beat Saïd and Hubert savagely. Vinz breaks up the fight at gunpoint and captures one of the skinheads. His plan to execute him is thwarted by his reluctance to go through with the deed, and, cleverly goaded by Hubert, he is forced to confront the fact that his heartless gangster pose does not reflect his true nature. Vinz lets the skinhead flee.

Early in the morning, the trio return home and Vinz turns the gun over to Hubert. Vinz and Saïd encounter a plainclothes officer whom Vinz had insulted earlier whilst with his friends on a local rooftop. The officer grabs and threatens Vinz, taunting him with a loaded gun held to his head. Hubert rushes to their aid, but the gun accidentally goes off, killing Vinz. As Hubert and the officer point their guns at each other and Saïd closes his eyes, a single gunshot is heard, with no indication of who fired or who may have been hit.

This stand-off is underlined by a voice-over of Hubert's slightly modified opening lines ("It's about a society in free fall..."), underlining the fact that, as the lines say, jusqu'ici tout va bien ("so far so good"); all seems to be going relatively well until Vinz is killed, and from there no one knows what will happen, a microcosm of French society's descent through hostility into pointless violence.

Cast

- Vincent Cassel as Vinz

- Hubert Koundé as Hubert

- Saïd Taghmaoui as Saïd

- Marc Duret as Inspector Notre Dame

- Abdel Ahmed Ghili as Abdel

- François Levantal as Astérix (called Snoopy in some English editions)

- Benoît Magimel as Benoît

- Andrée Damant as The concierge

- Philippe Nahon as Police Chief

- Zinedine Soualem as Plainclothes Police Officer

- Vincent Lindon as Really Drunk Guy

- Karin Viard as Gallery Girl

- Peter Kassovitz as Gallery Patron

- Mathieu Kassovitz as Skinhead

Production

Kassovitz has said that the idea came to him when a young Zairian, Makome M’Bowole, was shot in 1993. He was killed at point blank range while in police custody and handcuffed to a radiator. The officer was reported to have been angered by Makome's words, and had been threatening him when the gun went off accidentally.[3] Kassovitz began writing the script on April 6, 1993, the day M'Bowole was shot. He was also inspired by the case of Malik Oussekine, a 22-year-old student protester who died after being badly beaten by the riot police after a mass demonstration in 1986, in which he did not take part.[4] Oussekine's death is also referred to in the opening montage of the film.[5] Mathieu Kassovitz included his own experiences; he took part in riots, he acts in a number of scenes and includes his father Peter in another.

The majority of the filming was done in the Parisian suburb of Chanteloup-les-Vignes. Unstaged footage was used for this film, taken from 1986–96; riots still took place during the time of filming. To actually film in the projects, Kassovitz, the production team and the actors, moved there for three months prior to the shooting as well as during actual filming.[6] Due to the film's controversial subject matter, seven or eight local French councils refused to allow the film crew to film on their territory. Kassovitz was forced to temporarily rename the script Droit de Cité.[7] Some of the actors were not professionals and the film includes many situations that were based on real events.[6]

The music of the film was handled by French hardcore rap group Assassin, whose song "Nique La Police" (translated as "Fuck The Police") was featured in one of the scenes of the film. One of the members of Assassin, Mathias "Rockin' Squat" Crochon, is the brother of Vincent Cassel, who plays Vinz in the film.[5]

The film is dedicated to those who died while it was being made.

Reception

Upon its release, La Haine received widespread critical acclaim and was well received in France and abroad. The film was shown at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival where it enjoyed a standing ovation. Kassovitz was awarded the Best Director prize at the festival.[5] The film had a total of 2,042,070 admissions in France where it was the 14th highest-grossing film of the year.[1]

Based on 25 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an overall approval rating from critics of 100%, with an average score of 8.12/10. The site's consensus reads: "Hard-hitting and breathtakingly effective, La Haine takes an uncompromising look at long-festering social and economic divisions affecting 1990s Paris".[8] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called the film "raw, vital and captivating".[9] Wendy Ide of The Times stated that La Haine is "One of the most blisteringly effective pieces of urban cinema ever made."[10]

After the film was well received upon its release in France, Alain Juppé, who was Prime Minister of France at the time, commissioned a special screening of the film for the cabinet, which ministers were required to attend. A spokesman for the Prime Minister said that, despite resenting some of the anti-police themes present in the film, Juppé found La Haine to be "a beautiful work of cinematographic art that can make us more aware of certain realities."[7]

It was ranked #32 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[11]

Accolades

- Best Director (1995 Cannes Film Festival) - Mathieu Kassovitz[12]

- Best Editing (César Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz and Scott Stevenson

- Best Film (César Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Producer (César Awards) - Christophe Rossignon

- Best Young Film (European Film Awards) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Foreign Language Film (Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards)

- Best Director (Lumières Award) - Mathieu Kassovitz

- Best Film (Lumières Award) - Mathieu Kassovitz

Home media

La Haine was available on VHS in the United States, but was not released on DVD until The Criterion Collection released a 2-disc edition in 2007. The film has been shown on many Charter Communications Channels. Both HD DVD and Blu-ray versions have also been released in Europe, and Criterion released the film on Blu-ray in May 2012. The release includes audio commentary by Kassovitz, an introduction by actor Jodie Foster, "Ten Years of La Haine", a documentary that brings together cast and crew a decade after the film's landmark release, a featurette on the film's banlieue setting, production footage, and deleted and extended scenes, each with an afterword by Kassovitz.[13]

References

- "La Haine (1995)". JPBox-Office. 31 May 1995. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- JP. "La Haine (1995)- JPBox-Office". www.jpbox-office.com.

- Elstob, Kevin. "Hate (La Haine) review". Film Quarterly. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 51 (2 (Winter, 1997-1998)): 44–49. ISSN 0015-1386. JSTOR 3697140.

- Sciolino, Elaine (30 March 2006). "Violent Youths Threaten to Hijack Demonstrations in Paris". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- "La haine and after: Arts, Politics, and the Banlieue".

- "la HAINE". Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Johnston, Sheila (October 19, 1995). "Why the prime minister had to see La Haine". The Independent. London.

- "La Haine (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Thomas, Kevin (8 March 1996). "Compelling, Bleak Look at 'Hate'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Ide, Wendy (19 August 2004). "La Haine". The Times. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema | 32. La Haine". Empire. 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "Festival de Cannes: La Haine". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- "La haine". The Criterion Collection.

External links

- La Haine on IMDb

- La Haine at AllMovie

- La Haine at Box Office Mojo

- La Haine at Rotten Tomatoes

- Stanford University Review

- La haine and after: Arts, Politics, and the Banlieue an essay by Ginette Vincendeau at the Criterion Collection