Baltimore crisis

The Baltimore crisis was a diplomatic incident that took place between Chile and the United States, after the 1891 Chilean Civil War, as a result of the growing American influence in Pacific Coast region of Latin America in the 1890s. It marked a dramatic shift in United States–Chile relations. It was triggered by the stabbing of two United States Navy sailors from USS Baltimore in front of the "True Blue Saloon" in Valparaíso on October 16, 1891. The United States government demanded an apology. Chile ended the episode when it apologized and paid a $75,000 indemnity.

Background

In 1884 Chile emerged from the War of the Pacific as a potential threat to the hegemony of the United States.[2] The Chilean navy, then the strongest fleet in the Pacific, was able to confront American policy. In 1882 Chile refused US mediation in the War of the Pacific. During the Panama crisis of 1885, as the United States Navy occupied Colón, then part of Colombia, the Chilean government sent its most powerful protected cruiser (which represented a serious threat for the American wooden warships) to Panama City and ordered it not to leave until after the American forces evacuated Colon. Finally, in 1888 Chile annexed Easter Island, located some 2,000 miles west of Valparaíso, and by occupying Easter Island, Chile joined the imperial nations.[2](p53)

But by 1891 the equation of power had changed. The United States possessed more naval power and, more significantly,[3] Alfred Thayer Mahan's theories were needed to secure the growing influence of the United States in Latin America.[4]

During the Chilean Civil War the American government supported the forces of President Jose Manuel Balmaceda and enforced a ban on exports for the congressional forces that was supported partially by the United Kingdom. These and another circumstances troubled relations between the United States and the victorious congressionalist side, who in 1891 defeated the presidential forces and were then in power in Chile.

Just before the end of the Chilean Civil War the United States sent a group of ships including USS Charleston to force the Chilean congressional cargo ship Itata, that illegally loaded arms in San Diego for the congressional forces, to return to San Diego. The US ships reached Iquique before Itata. The new Chilean government ordered the ship back to San Diego to face outstanding charges.

During the war the American owned Central and South American Cable Company, by order of the Balmaceda administration, restored submarine telegraph cable service between Santiago and Lima and sundered the cable connection to the congressional headquarters.

In addition, the United States minister in Santiago gave diplomatic asylum to various insurgent congressional leaders during the war and to Balmaceda's supporters after the war. The victorious side called upon the American minister in Santiago, Patrick Egan, to surrender the newest refugees to the authorities but it was refused.

From the congressionalist's point of view, the United States had tried to stop them from purchasing weapons, denied the congressionalist rebels access to international telegraph traffic, spied on the congressional troops, and refused to surrender war criminals.

USS Baltimore incident

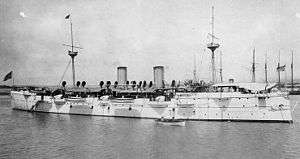

On October 16, 1891, a mob attacked a group of sailors on shore leave from the cruiser USS Baltimore outside a bar in the Chilean port of Valparaíso after one of the American sailors spit on a picture of Arturo Prat, one of Chile's national heroes. Two sailors were killed and seventeen or eighteen were injured.

The new Chilean government initially rejected American protests. However, after United States President Benjamin Harrison sent a strong message to the United States Congress, Chile apologized and paid $75,000 in gold.[5]

See also

- 1891 Chilean Civil War

Notes

- William Sater, Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict, Athens, GA; University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-1249-5 p.51

- William Sater, Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict, 1990 by the University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-1249-5, page 66:

- 'particularly Alfred Thayer Mahan's blue water boys- bristled with joy at the prospect of unleashing their recently acquired naval weapons against Santiago

- William Sater, Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict, 1990 by the University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-1249-5, page 64:

- It became clear that Harrison saw the issue as a matter of American prestige:"We must protect those who, in foreign ports, display the flag or wear the colors of this government against insult, brutality, and death, inflicted in resentement of the acts of their government ..."

- Magazine Harper's Weekly, November 14, 1891, A Very Mischievous Boy, written by Robert C. Kennedy (reproduction of the magazine article retrieved on 5. March 2011)

Further reading

- Devine, Michael. John W. Foster (The Ohio University Press, 1981)

- Goldberg, Joyce S. "Consent to Ascent. The Baltimore Affair and the US Rise to World Power Status." The Americas (1984): 21-35. in JSTOR

- Goldberg, Joyce S. The "Baltimore" Affair (Univ of Nebraska Press, 1986)

- Hardy, Osgood (May 1922). "The Itata Incident". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 5 (2): 195–226. doi:10.2307/2506025. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2506025. OCLC 3518594.

- Moore, John Bassett. "The Late Chilian Controversy" Political Science Quarterly, (1893) vol 8#3 pp: 467–94. in JSTOR

Primary sources

- Foreign Relations of the United States of America for the Year 1891. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1892.

- Foreign Relations of the United States of America for the Year 1892. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1893.

- The Federal Reporter. vv 47-9, 56

- Message of the President of the United States Respecting the Relations with Chile. Benjamin Harrison, Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1892, 664 pp.

- Histamar sobre el tema (in Spanish)

- General History of the Foreign Affairs of Argentina (in Spanish)