Baccio Baldini

Baccio Baldini (c. 1436 – buried 12 December 1487) was an Italian goldsmith and engraver of the Renaissance, active in his native Florence. All that is known of Baldini's life, apart from the date of his burial in Florence,[1] is what Vasari says of him: that Baldini was a goldsmith and pupil of Maso Finiguerra, the Florentine goldsmith who was, according to Vasari's incorrect claim,[2] the inventor of engraving. Vasari says Baldini based all of his works on designs by Sandro Botticelli because he lacked disegno himself.[3] Today Baldini is best remembered for his collaboration with Botticelli on the first printed Dante in 1481, where it is believed the painter supplied the drawings for Baldini to turn into engravings, but it does not seem to be the case that all his work was after Botticelli. He has long been attributed with a number of other engravings as the leading practitioner of the Florentine Fine Manner of engraving, this rather tentatively; he is often given a "workshop" or "circle" to ease uncertainty.[4]

In total the group amounts to over 100 prints.[5] They are "characterized by rather sharp, often deeply incised outlines: similar deeply-cut graver work for the features, for the ample ornament of the costumes, and for the architecture; and extremely fine lines, organized into rather fuzzy cross-hatching, for the shading, which often gives the draperies an almost furry look". This technique was designed to capture the quality of pen and wash drawings, and he may be attributed with drawings as well.[6]

He, or his circle, have been attributed with the Florentine Picture-Chronicle in the British Museum, an album of 55 drawings of scenes and figures of ancient history.[7] Jay Levinson has also attributed to him several of the Otto Prints "a group of delightful engravings, mostly in the round, showing amorous subjects or hunting scenes; they were intended to be pasted into gift boxes", which are also in the British Museum (they survive in unique impressions, presumably from a collection for customers to choose from).[8] However, in 2017 the British Museum was not prepared to name Baldini as the artist of these, or any other works in their collection.[9] Hugo Chapman points out that there is "no contemporary reference to Baldini making prints" at all,[10] and Vasari was writing almost a century after his career is supposed to have begun.

Whoever the artists were, the prints attributed to Baldini and the drawings in the Florentine Picture-Chronicle share "a goldsmith-inspired predeliction for intricate surface pattern and ornament; a rather rudimentary grasp of perspective" (less so in some prints), and a dependence on "Finiguerra-inspired figure types".[11]

The "Fine Manner" in Florentine engraving

From about 1460–1490 two styles developed in Florence, which remained the largest centre of Italian engraving. These are called (although the terms are less often used now) the "Fine Manner" and the "Broad Manner", referring to the typical thickness of the lines used to produce shading within the main contour lines. The terms are somewhat compromised by a division of the Broad Manner into two groups with a different technique, both found in the works probably by Francesco Rosselli. He appears to have not only introduced to Florence the German-style burin with a lozenge-shaped section that the technique requires, but to have subsequently reinvented his technique. The leading artists in the Fine Manner are Baccio Baldini and the "Master of the Vienna Passion", and in the Broad Manner, Francesco Rosselli and Antonio Pollaiuolo, whose only print was the Battle of the Nude Men the masterpiece of 15th-century Florentine engraving.[12] The problems with the terms are exemplified by Konrad Oberhuber describing this print as "the major work of the Broad Manner",[13] while for David Landau it is "a masterpiece in the Fine Manner".[14]

Engravings after Botticelli

Botticelli had a lifelong interest in the great Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, which produced works in several media.[15] According to Vasari, he "wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante", which is also referred to dismissively in another story in the Life,[16] but no such text has survived.

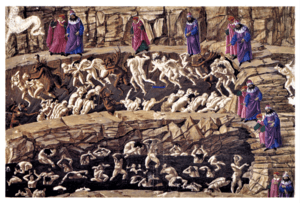

Vasari wrote disapprovingly of the first printed Dante in 1481 with engravings by Baccio Baldini, engraved from drawings by Botticelli: "being of a sophistical turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work led to serious disorders in his living."[17] Vasari, who lived when printmaking had become far more important than in Botticelli's day, never takes it seriously, perhaps because his own paintings did not sell well in reproduction. Botticelli's attempt to design the illustrations for a printed book was unprecedented for a leading painter, and though it seems to have been something of a flop, this was a role for artists that had an important future.[18]

The Divine Comedy consists of 100 cantos, and the printed text left space for one engraving for each canto. However, only 19 illustrations were engraved, and most copies of the book have only the first two or three. The first two, and sometimes three, are usually printed on the book page, while the later ones are printed on separate sheets that are pasted into place. This suggests that the production of the engravings lagged behind the printing, and the later illustrations were pasted into the stock of printed and bound books, and perhaps sold to those who had already bought the book. Unfortunately Baldini was neither very experienced nor talented as an engraver, and was unable to express the delicacy of Botticelli's style in his plates.[19] Two religious engravings are also generally accepted to be after designs by Botticelli.[20]

Botticelli later began a luxury manuscript illustrated Dante on parchment, most of which was taken only as far as the underdrawings, and only a few pages are fully illuminated. This manuscript has 93 surviving pages (32 x 47 cm), now divided between the Vatican Library (8 sheets) and Berlin (83), and represents the bulk of Botticelli's surviving drawings.[21] Once again, the project was never completed, even at the drawing stage, but some of the early cantos appear to have been at least drawn but are now missing. The pages that survive have always been greatly admired, and much discussed, as the project raises many questions.

Florentine Picture-Chronicle

This album, an unusual and ambitious attempt at a "pictorial chronicle of the world", which was never completed, once belonged to John Ruskin.[22] The drawings are in black chalk, then ink and usually wash.[23] The final drawing of the 55 is an unfinished one of Milo of Croton,[24] perhaps some two-thirds of the way through the intended scheme. Many drawings show a single figure, usually standing in a landscape, but others are rather elaborate narrative scenes.[25] Apart from a general stylistic similarity to the prints attributed to Baldini, there are some specific borrowings (in whichever direction), or use of a common source.[26]

A print attributed to Baldini of Theseus and Ariadne by the Cretan Labyrinth uses the same dominating labyrinth as the Picture-Chronicle's drawing of Theseus,[27] and the drawing of Jacob and Esau uses several animals in a "Baldini" pattern sheet print of animals, the only impression of which is also in the British Museum.[28]

Following a thesis by Lucy Whitaker (1986) it is "firmly established" that at least two artists worked on the drawings,[29] and it is possible that Baldini was actually neither of these, though they are clearly close to the prints given to him.[30] The British Museum attributed the album in 2017 to "Circle/School of: Baccio Baldini; Circle/School of: Maso Finiguerra".[31] When first published in 1893, by Sidney Colvin (published by the Imperial Press, Berlin) it was attributed to Finiguerra.[32]

Other works

He is attributed with a set of 24 Prophets and 12 Sibyls, all shown seated at full-length, with verses underneath, copied by Francesco Rosselli and others, and a series of The Planets.[33] Engravings by Baldini were published in 1477 illustrating Monte Santo di Dio, a religious work by Antonio Bettini, printed by Nicolaus Laurentii.[34] Baldini did the first of a series on the Triumphs of Petrarch; the rest are by the Master of the Vienna Passion.[35] Other large individual prints are a Conversion of Saint Paul, in a unique impression in Hamburg,[36] and a Judgement hall of Pontius Pilate, "known only in a very late reworked state and therefore difficult to judge".[37]

Notes

- He is assumed to be the "Baccio orafo" ("Baccio the jeweller") buried in San Lorenzo, Florence on 12 December 1487; Levinson, 13 note 1

- Levinson, xv

- Levinson, 13

- Levinson, xvii, 15

- Chapman, 170

- Levinson, 15

- British Museum page on a print attributed to Baldini; Levinson, 15

- Levinson, 15

- "Baccio Baldini (Biographical details)", British Museum, "Nothing in BM is kept under his name".

- Chapman, 170

- Chapman, 170

- Levinson, xvii-xix, 47-80 on Rosselli and Pollaiuolo; Landau and Parshall, 65, 72–76.

- Levinson, xviii

- Landau and Parshall, 73

- Lightbown, 16–17, 86–87

- Vasari, 152, 154

- Vasari, 152, a different translation

- Landau, 35, 38

- Lightbown, 89; Landau, 108; Dempsey

- Lightbown, 302

- Lightbown, 280; some are drawn on both sides of the sheet.

- Chapman, 166

- Chapman, 166

- Chapman, 166

- Chapman, 166-171

- Chapman, 170-171

- Chapman, 170-171; Print attributed to Baldini of Theseus and Ariadne by the Cretan Labyrinth, British Museum

- Chapman, 170-171; print of animals attributed to Baldini, British Museum page

- Chapman, 167

- Chapman, 170-171

- 'The Florentine Picture-Chronicle' page from the album, British Museum.

- Levinson, 15-16; The Florentine Picture-Chronicle, Being a Series of Ninety-Nine Drawings Representing Scenes and Personages of Ancient History Sacred and Profane, chronologia.org, with images of each page

- Levinson, 16, 18, 22-38

- Levinson, 15

- Levinson, xvii, 15

- Levinson, 16

- Levinson, 18; Judgement hall of Pontius Pilate, MFA Boston

References

- Chapman, Hugo, in Chapman, Hugo, and Faietti, Marzia, Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings, 2010, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714126678

- Dempsey, Charles, "Botticelli, Sandro", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 15 May. 2017. subscription required

- Landau, David, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Levinson, Jay A. (ed. - entries by Konrad Oberhuber) Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), 1973, LOC 7379624

- Lightbown, Ronald, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 1989, Thames and Hudson

- Vasari, selected & ed. George Bull, Artists of the Renaissance, Penguin 1965 (page nos from BCA edn, 1979). Vasari Life on-line (in a different translation)

Further reading

- Mark J. Zucker, 'The Illustrated Bartsch, Commentary', vol. 24, part 1, 1993, pp. 89–93, 240

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baccio Baldini. |