Babe Adams

Charles Benjamin "Babe" Adams (May 18, 1882 – July 27, 1968) was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1906 to 1926 who spent nearly his entire career with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Noted for his outstanding control, his career average of 1.29 walks per 9 innings pitched was the second lowest of the 20th century; his 1920 mark of 1 walk per 14.6 innings was a modern record until 2005. He shares the Pirates' franchise record for career victories by a right-hander (194), and holds the team mark for career shutouts (47); from 1926 to 1962, he held the team record for career games pitched (481).

| Babe Adams | |||

|---|---|---|---|

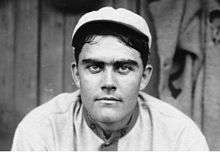

Adams in 1911 | |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: May 18, 1882 Tipton, Indiana | |||

| Died: July 27, 1968 (aged 86) Silver Spring, Maryland | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| April 18, 1906, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| August 11, 1926, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 194–140 | ||

| Earned run average | 2.76 | ||

| Strikeouts | 1,036 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Early life

Adams was born in Tipton, Indiana. As a child, he moved to Mount Moriah, Missouri, where baseball was popular. After he was discovered by a Missouri-based scout in 1904, he was signed to play minor league baseball with the Parsons Preachers of the Missouri Valley League in 1905.[1]

Major league career

He made his MLB debut on April 18, 1906, with the St. Louis Cardinals, taking the loss in a 4-inning start, but did not pitch again for them. In September 1907, his contract was sold to the Pirates. After going 12–3 with a 1.11 earned run average (ERA) in the 1909 regular season, his first full year, Adams became the star of the 1909 World Series after being named the surprise starter of Game 1 following a tip by National League president John Heydler that Adams' style was similar to that of an AL pitcher whom the Detroit Tigers had difficulty playing against. He won three complete game victories – each of them a six-hitter. With a shutout in Game 7, Adams became the first rookie in World Series history to start and win Game 7, which has only been repeated by John Lackey in 2002. He was also the only member of that team who would be on the Pirates' World Series champions in 1925. He later won 20 games in both 1911 and 1913. An off-year in 1916 that saw his ERA rise to 5.72 got him farmed out to the Western Association, but late in 1918 he found his stride again and rejoined the Pirates, where he stayed until 1926.

On May 4, 1913, Adams' third inning triple drove in Billy Kelly for the Pirates only hit and run, Adams held the Cincinnati Reds to only 2 hits and a walk for a 1–0 victory at Redland Field.

Adams was known as an excellent control pitcher. On July 17, 1914, he pitched a 21-inning game against the New York Giants without allowing a single walk, surrendering only 12 hits, but losing 3–1 on Larry Doyle's home run in the top of the 21st; it is the longest game without a walk in major league history.[2] Rube Marquard also went the distance for New York to gain the victory, allowing two walks. In 1920, Adams allowed only 18 walks in 263 innings.

In his career, Adams had a 194–140 win-loss record and a 2.76 ERA. His last game was on August 11, 1926; he was released days later after joining a group of players who requested that former manager and team vice president Fred Clarke, who had been openly criticizing manager Bill McKechnie, not be permitted to sit on the bench. He never played another major league game.

Adams was a better than average hitting pitcher in his major league career, compiling a .212 batting average (216-for-1,019) with 79 runs, 3 home runs, 75 RBI and drawing 53 bases on balls. Defensively, he was a better-than-average fielding pitcher, recording a .976 fielding percentage which was 24 points higher than the league average at that position.

Later life

Adams later managed in the minor leagues, farmed in Mount Moriah, Missouri, and worked as a reporter and foreign correspondent during World War II and the Korean War. Adams died of throat cancer in Silver Spring, Maryland, at age 86.

References

- Carmichael, John P. (1996). My Greatest Day in Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0803263686. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Gustines, Elena. "Baseball's Enduring Oddities". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Babe Adams at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- Babe Adams at Find a Grave