B53 nuclear bomb

The Mk/B53 was a high-yield bunker buster thermonuclear weapon developed by the United States during the Cold War. Deployed on Strategic Air Command bombers, the B53, with a yield of 9 megatons, was the most powerful weapon in the U.S. nuclear arsenal after the last B41 nuclear bombs were retired in 1976.

| B53 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Thermonuclear weapon |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1962–1997 |

| Production history | |

| Designer | LANL[1] |

| Designed | 1958–1961[1] |

| Manufacturer | Atomic Energy Commission |

| Produced | 1961–1965[1][2] |

| No. built | About 340[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 8,850 lb (4,010 kg)[1] |

| Length | 12 ft 4 in (3.76 m)[1] |

| Diameter | 50 in (4.2 ft; 1.3 m)[1] |

| Filling | Fission: 100% oralloy Fusion: Lithium-6 deuteride[1] |

| Blast yield | Y1: 9 megatons Y2: Unknown |

The B53 was the basis of the W-53 warhead carried by the Titan II Missile, which was decommissioned in 1987. Although not in active service for many years before 2010, fifty B53s were retained during that time as part of the "hedge" portion[lower-roman 1] of the Enduring Stockpile until its complete dismantling in 2011. The last B53 was disassembled on 25 October 2011, a year ahead of schedule.[3][4]

With its retirement, the largest bomb currently in service in the U.S. nuclear arsenal is the B83, with a maximum yield of 1.2 megatons.[5] The B53 was replaced in the bunker-busting role by the B61 Mod 11.

History

Development of the weapon began in 1955 by Los Alamos National Laboratory, based on the earlier Mk 21 and Mk 46 weapons. In March 1958 the Strategic Air Command issued a request for a new Class C (less than five tons, megaton-range) bomb to replace the earlier Mk 41.[2] A revised version of the Mk 46 became the TX-53 in 1959. The development TX-53 warhead was apparently never tested, although an experimental TX-46 predecessor design was detonated 28 June 1958 as Hardtack Oak, which detonated at a yield of 8.9 Megatons.

The Mk 53 entered production in 1962 and was built through June 1965.[2] About 340 bombs were built. It entered service aboard B-47 Stratojet, B-52G Stratofortress,[1] and B-58 Hustler bomber aircraft in the mid-1960s. From 1968 it was redesignated B53.

Some early versions of the bomb were dismantled beginning in 1967. About 50 bomb and 54 Titan warhead versions were in service through 1980. After the Titan II program ended, the remaining W-53s were retired in the late 1980s. The B53 was also intended to be retired in the 1980s, but 50 units remained in the active stockpile until the deployment of the B61-11 in 1997. At that point the obsolete B53s were slated for immediate disassembly; however, the process of disassembling the units was greatly hampered by safety concerns as well as a lack of resources.[6] In 2010 authorization was given to disassemble the 50 bombs at the Pantex plant in Texas.[7] The process of dismantling the last remaining B53 bomb in the stockpile was completed in 2011.[8][9]

Specifications

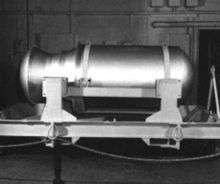

The B53 was 12 feet 4 inches (3.76 m) long with a diameter of 50 inches (4.17 ft; 1.27 m). It weighed 8,850 pounds (4,010 kg), including the W53 warhead, the 800-to-900 lb (360-to-410 kg) parachute system and the honeycomb aluminum nose cone to enable the bomb to survive laydown delivery. It had five parachutes:[1] one 5-foot (1.52 m) pilot chute, one 16-foot (4.88 m) extractor chute, and three 48-foot (14.63 m) main chutes. Chute deployment depends on delivery mode, with the main chutes used only for laydown delivery. For free-fall delivery, the entire system was jettisoned.

The W53 warhead of the B53 used oralloy (highly enriched uranium) instead of plutonium for fission , with a mix of lithium-6 deuteride fuel for fusion. The explosive lens comprised a mixture of RDX and TNT, which was not insensitive. Two variants were made: the B53-Y1, a "dirty" weapon using a U-238-encased secondary, and the B53-Y2 "clean" version with a non-fissile (lead or tungsten) secondary casing. The explosive yield for the Y1 version was declassified in 2014 and is known to be 9 Mt.[10]

Role

It was intended as a bunker buster weapon, using a surface blast after laydown deployment to transmit a shock wave through the earth to collapse its target. Attacks against the Soviet deep underground leadership shelters in the Chekhov/Sharapovo area south of Moscow envisaged multiple B53/W53 exploding at ground level. It has since been supplanted in such roles by the earth-penetrating B61 Mod 11, a bomb that penetrates the surface to deliver much more of its explosive energy into the ground, and therefore needs a much smaller yield to produce the same effects.

The B53 was intended to be retired in the 1980s, but 50 units remained in the active stockpile until the deployment of the B61-11 in 1997. At that point the obsolete B53s were slated for immediate disassembly; however, the process of disassembling the units was greatly hampered by safety concerns as well as a lack of resources.[6][7] The last remaining B53 bomb began the disassembly processes on Tuesday, 25 October 2011 at the Energy Department's Pantex Plant.[4]

An April 2014 GAO report notes that the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is retaining canned sub-assemblies (CSAs) "associated with a certain warhead indicated as excess in the 2012 Production and Planning Directive are being retained in an indeterminate state pending a senior-level government evaluation of their use in planetary defense against earthbound asteroids."[11] In its FY2015 budget request, the NNSA noted that the B53 component disassembly was "delayed", leading some observers to conclude they might be the warhead CSAs being retained for potential planetary defense purposes.[12]

W-53

The W-53 nuclear warhead of the Titan II ICBM used the same physics package as the B53, without the air drop-specific components like the parachute system and crushable structures in the nose and sides needed for lay-down delivery, reducing its mass to about 6,200 lb (2,800 kg).[13] The 8,140-pound (3,690 kg) Mark-6 re-entry vehicle containing the W53 warhead was about 123 inches (10.3 ft; 3.1 m) long, 7.5 feet (2.3 m) in diameter and was mounted atop a spacer which was 8.3 feet (2.5 m) in diameter at the missile interface (compared to the missile's core diameter of 10 feet [3.0 m]). With a yield of 9 megatons, it was the highest yield warhead ever deployed on a US missile. About 65 W53 warheads were constructed between December 1962 and December 1963.[13]

On 19 September 1980 a fuel leak caused a Titan II to explode within its silo in Arkansas, throwing the W53 warhead some distance away. Due to the safety measures built into the weapon, it did not explode or release any radioactive material.[14] Fifty-two active missiles were deployed in silos prior to the beginning of the retirement program in October 1982.[13]

Effects

Assuming a detonation at optimum height, a 9 megaton blast would result in a fireball with an approximate 2.9 to 3.4 mi (4.7 to 5.5 km) diameter.[15] The radiated heat would be sufficient to cause lethal burns to any unprotected person within a 20-mile (32 km) radius (1,250 sq mi or 3,200 km2). Blast effects would be sufficient to collapse most residential and industrial structures within a 9 mi (14 km) radius (254 sq mi or 660 km2); within 3.65 mi (5.87 km) (42 sq mi or 110 km2) virtually all above-ground structures would be destroyed and blast effects would inflict near 100% fatalities. Within 2.25 mi (3.62 km) a 500 rem (5 Sievert) dose of ionizing radiation would be received by the average person, sufficient to cause a 50% to 90% casualty rate independent of thermal or blast effects at this distance.[16]

Artifacts

- B53 on display in the free introduction exhibit room at the Atomic Testing Museum, Las Vegas, Nevada

- B53 on display at the Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum at the former Lowry AFB, Denver, Colorado

- B53 on display at the Grissom Air Museum at Grissom Air Reserve Base, the former Grissom AFB, in Peru, Indiana

- Mark 53 casing is on display in the Cold War Gallery at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio

- B53 casing in display yard of The National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, adjacent to Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque, New Mexico

- W-53 on display in the visitors center of the Titan Missile Museum near Tucson, Arizona

Notes

- 'Hedge stockpile': fully operational, but kept in storage; available within minutes or hours; not connected to delivery systems, but delivery systems are available (i.e. missile and bomb stockpiles kept at various Air Force bases)

References

- Cochran 1989, p. 58

- Hansen 1988, pp. 162–163

- Blaney, Betsy (25 October 2011). "US's most powerful nuclear bomb being dismantled". The Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Ackerman, Spencer (23 October 2011). "Last Nuclear 'Monster Weapon' Gets Dismantled". Wired. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Betsy, Blaney (25 October 2011). "Most powerful US nuclear bomb dismantled". NBC News. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Johnston, William Robert (6 April 2009). "Multimegaton Weapons: The Largest Nuclear Weapons". Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Walter Pincus (19 October 2010). "The Story Of The B-53 'Bunker Buster' Offers A Lesson In Managing Nuclear Weapons". The Washington Post. p. 13. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Editors of the National Catholic Reporter (21 March 2013). Best Catholic Spirituality Writing 2012: 30 Inspiring Essays from the National Catholic Reporter. eBooks2go. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-1-61813-984-9.

- Moury, Matthew; Majldl, Vahld (28 November 2014). (U)DECLASSIFICATION DETERMINATION (PDF) (Report). p. US DoD. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

that the total weapon yield of the B53/W53 Y1 was 9 Mt.

- ""Actions Needed by NNSA to Clarify Dismantlement Performance Goal", Report to the Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate, United States Government Accountability Office," (PDF). April 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- "Department of Energy FY 2015 Congressional Budget Request for the National Nuclear Security Administration" (PDF). March 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- Cochran 1989, p. 59

- "Titan II at Little Rock AFB". The Military Standard. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer". Fourmilab. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Wellerstein, Alex (2012–2014). "NukeMap v2.42". NukeMap. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

Bibliography

- Cochran, Thomas B. (1989). "US Nuclear Stockpile". Nuclear Weapons Databook: United States Nuclear Forces and Capabilities (PDF). 1. Ballinger Pub Co. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-88730-043-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Hansen, Chuck (1988). US Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History. Arlington, Texas: Aerofax. ISBN 978-0-517-56740-1.