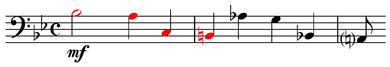

BACH motif

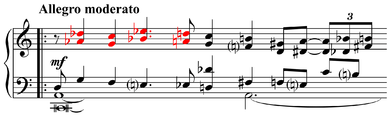

In music, the BACH motif is the motif, a succession of notes important or characteristic to a piece, B flat, A, C, B natural. In German musical nomenclature, in which the note B natural is named H and the B flat named B, it forms Johann Sebastian Bach's family name. One of the most frequently occurring examples of a musical cryptogram, the motif has been used by countless composers, especially after the Bach Revival in the first half of the 19th century.

Origin

Johann Gottfried Walther's Musicalisches Lexikon (1732) contains the only biographical sketch of Johann Sebastian Bach published during the composer's lifetime. There the motif is mentioned thus:[1]

...all those who carried the name [Bach] were as far as known committed to music, which may be explained by the fact that even the letters b a c h in this order form a melody. (This peculiarity was discovered by Mr. Bach of Leipzig.)

This reference work thus indicates Bach as the inventor of the motif.

Usage in compositions

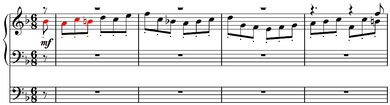

The BACH motif from The Art of Fugue Contrapunctus XIXc is the "'1st Theme'/fugue subject" of Ives' combined sonata-allegro and fugal procedures.[4]

In a comprehensive study published in the catalogue for the 1985 exhibition "300 Jahre Johann Sebastian Bach" ("300 years of Johann Sebastian Bach") in Stuttgart, Germany, Ulrich Prinz lists 409 works by 330 composers from the 17th to the 20th century using the BACH motif.[5] A similar list is available in Malcolm Boyd's volume on Bach: it also contains some 400 works.[6]

Bach used the motif in a number of works, most famously as a fugue subject in the last Contrapunctus of The Art of Fugue. The motif also appears in the end of the fourth variation of Bach's Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her", as well as in other pieces.[7] For example, the first measure of the Sinfonia in F minor BWV 795 includes a transposed version of the motif (a♭'-g'-b♭'-a') followed by the original in measure 17.[8]

Later commentators wrote: "The figure occurs so often in Bach's bass lines that it cannot have been accidental."[9] Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht goes as far as to reconstruct Bach's putative intentions as an expression of Lutheran thought, imagining Bach to be saying, "I am identified with the tonic and it is my desire to reach it ... Like you I am human. I am in need of salvation; I am certain in the hope of salvation, and have been saved by grace," through his use of the motif rather than a standard changing tone figure (B♭-A-C-B) in the double discant clausula in the fourth fugue of The Art of Fugue.[10]

The motif was used as a fugue subject by Bach's son Johann Christian, and by his pupil Johann Ludwig Krebs. It also appears in a work by Georg Philipp Telemann.[11]

The motif's wide popularity came only after the start of the Bach Revival in the first half of the 19th century.[7] A few mid-19th century works that feature the motif prominently are:

- 1845 – Robert Schumann: Sechs Fugen über den Namen: Bach, for organ, pedal piano, or harmonium, Op. 60[2][12]

- 1855 – Franz Liszt: Fantasy and Fugue on the Theme B-A-C-H, for organ (later revised, 1870, and arranged, 1871, for piano)[13]

- 1856 – Johannes Brahms: Fugue in A-flat minor for organ, WoO 8[12]

Composers found that the motif could be easily incorporated not only into the advanced harmonic writing of the 19th century, but also into the totally chromatic idiom of the Second Viennese School; so it was used by Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and their disciples and followers. A few 20th-century works that feature the motif prominently are:

- 1926–28 – Arnold Schoenberg: Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31[14]

- 1937–38 – Anton Webern: String Quartet (the tone row is based on the BACH motif)[15]

- 1951–55 – Luigi Dallapiccola:

- 1968–81 – Alfred Schnittke:

- 1968: Quasi Una Sonata (repeated motif, one reviewer, "noting that B-A-C-H is the victor of the composition")[17]

- 1981: Symphony No. 3 – used alongside the monograms of several other composers.[18]

In the 21st century, composers continue writing works using the motif, frequently in homage to Johann Sebastian Bach.[7]

Further reading

- Seyoung Jeong (2009). Four Modern Piano Compositions Incorporating the B-A-C-H Motive. ISBN 3-8364-9768-9.

- Schuyler Watrous Robinson (1972). The B–A–C–H Motive in German Keyboard Compositions from the Time of J.S. Bach to the Present (thesis, University of Illinois)

References

- Johann Gottfried Walther Musicalisches Lexicon oder Musicalische Bibliothec, p. 64. Leipzig, W. Deer. 1732.

- Christopher Alan Reynolds (2003). Motives for Allusion: Context and Content in Nineteenth-Century Music, p.31. ISBN 0-674-01037-X.

- Daverio, John (1997). Robert Schumann: Herald of a "New Poetic Age", p.309. ISBN 0-19-509180-9.

- Crist, Stephen (2002). Bach Perspectives: Vol. 5: Bach in America, p.175. ISBN 0-252-02788-4. "The reference could not be more clear."

- Ulrich Prinz, Joachim Dorfmüller and Konrad Küster (1985). Die Tonfolge B–A–C–H in Kompositionen des 17. bis 20. Jahrhunderts: ein Verzeichnis, in: 300 Jahre Sebastian Bach (exhibition catalogue), pp. 389–419. ISBN 3-7952-0459-3

- Malcolm Boyd (1999). Bach. Oxford University Press. 2006 edition: ISBN 0-19-530771-2.

- Boyd, Malcolm (2001). "B-A-C-H". In Root, Deane L. (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press.

- Schulenberg, David (2006). The Keyboard Music of J.S. Bach, p.197. ISBN 0-415-97399-6.

- Marshall, Robert (2003). Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music, p.201 and p.224n18. ISBN 0-415-96642-6. See Godt 1979.

- Eggebrecht (1993:8) cited in Cumming, Naomi (2001). The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification, p.256. ISBN 0-253-33754-2.

- Jones, Ben. "B-A-C-H motif in Oboe Concerto, TWV 51:D6 (Telemann, Georg Philipp)". IMSLP. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

there is a clear B.A.C.H. motif at the beginning of the Adagio

- Platt, Heather Anne (2003). Johannes Brahms, p.243. ISBN 0-8153-3850-3.

- Arnold, Ben (2002). The Liszt Companion, p.173. ISBN 0-313-30689-3.

- Stein, Erwin (ed.). 1987. Arnold Schoenberg letters, p. 206. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06009-8

- Bailey, Kathryn. 2006. The Twelve-note Music of Anton Webern: Old Forms In a New Language, p. 24. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54796-3

- Fearn, Raymond (2003). The Music of Luigi Dallapiccola. 2005: ISBN 1-58046-078-X.

- Schmelz, Peter J. (2009). Such Freedom, If Only Musical, p. 255–56. ISBN 0-19-534193-7.

- Ivashkin, Alexander (2009) Liner notes to BIS complete symphony cycle, BIS-CD-1767-68

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BACH motif. |

- List of compositions with the theme "B-A-C-H": Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)