Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation

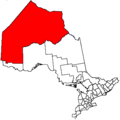

Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation (also known as Grassy Narrows First Nation or the Asabiinyashkosiwagong Nitam-Anishinaabeg in the Ojibwe language) is an Ojibwe First Nations band government who inhabit northern Kenora in Ontario, Canada. Their landbase is the 4,145 ha (10,240 acres) English River 21 Indian Reserve. It has a registered population of 1,595 as of October 2019, of which the on-reserve population was 971[2] They are a signatory to Treaty 3.

English River 21 Asabiinyashkosiwagong | |

|---|---|

| English River Indian Reserve No. 21 | |

English River 21 | |

| Coordinates: 50°11′N 94°02′W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| District | Kenora |

| First Nations | Asubpeeschoseewagong |

| Area | |

| • Land | 39.69 km2 (15.32 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 638 |

| • Density | 16.1/km2 (42/sq mi) |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Politics

|

|

Culture

|

|

Demographics

|

|

Religions |

|

Index

|

|

Wikiprojects Portals

WikiProject

First Nations Inuit Métis |

Governance

The First Nation is headed by a Chief and four councillors:

- Chief Rudy Turtle

- Cody Keewatin

- John C. Kokopenace Sr.

- Jason Kejick Sr.

- Alana Pahpasay

The First Nation is a member of the Bimose Tribal Council, a regional non-political Chief's Council, who is a member of the Grand Council of Treaty 3, a political organization.

The reserve is also part of the provincial riding of Kenora-Rainy River and federal riding of Kenora.

History

Although the Asubpeeschoseewagong people themselves say that they have always lived along the Wabigoon-English River northeast of Lake of the Woods, most historians believe that the ancestors of the Northern Ojibway were first encountered by Europeans near what is now Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and thus were given the name Saulteaux. Their territory was on the northern shore of the Great Lakes from the Michipicoten Bay of Lake Superior to the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. Participation in the North American fur trade was initially through trading of furs trapped by other tribes, but soon the Saulteaux acquired trapping skills and emigrated to their present location as they sought productive trapping grounds.[3]

Treaty 3

In 1871, Grassy Narrows First Nation, together with other Ojibway tribes, made a treaty with the Canadian government, The Crown, in the person of Queen Victoria, giving up aboriginal title to a large tract of land in northwestern Ontario and eastern Manitoba, Treaty 3 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux Tribe of the Ojibbeway Indians at the Northwest Angle on the Lake of the Woods with Adhesions. In exchange a spacious tract of land, as much as a square mile of land for each family, in a favourable location on the Wabigoon-English River system was reserved for the use of the tribe. Tribal members were allowed to hunt, fish, and trap on unused portions of their former domain; the government undertook to establish schools; and to give ammunition for hunting, twine to make nets, agricultural implements and supplies, and a small amount of money to the tribe. Alcoholic beverages were strictly forbidden.[4]

Old reserve

On the lands they selected under Treaty 3, the old reserve, the cycle of seasonal activities and traditional cultural practices of the Ojibway were followed. The people continued to live in their customary way, each clan living in log cabins in small clearings; often it was 1⁄2 mi (0.80 km) to the nearest neighbour. Each parcel was selected for access to fishing and hunting grounds and for suitability for gardening. The winters were spent trapping for the Hudson's Bay Company, the summer gardening and harvesting wild blueberries which together with skins were sold for supplies. Potatoes were grown on a community plot. In the fall, wild rice was harvested from the margins of the rivers and finished for storage. Muskrat were plentiful and trapped for pelts and food. There were deer and moose on the reserve which were hunted for meat and supplemented by fish. Work was available as hunting and fishing guides and cleaning tourist lodges. White people seldom entered the reserve except for the treaty agent who visited once a year. The only access to the reserve was by canoe or plane.[5] From 1876 to 1969 schooling was at McIntosh Indian Residential School, a residential school in McIntosh, Ontario.[6]

Economic and environmental issues

Mercury contamination

The First Nations people experienced mercury poisoning from Dryden Chemical Company, a chloralkali process plant, located in Dryden that supplied both sodium hydroxide and chlorine used in large amounts for bleaching paper during production for the Dryden Pulp and Paper Company.[7] The Dryden Chemical company discharged their effluent into the Wabigoon-English River system.[7] It is believed that approximately 10 tons (20,000 pounds) of mercury was dumped into the Wabigoon River system between 1962 and 1970.[8][9][10] Both the paper and chemical companies ceased operations in 1976, after 14 years of operations.[11] However, time has not lowered the levels of mercury in the Wabigoon River system as the paper and pulp industry in Dryden and the Canadian government had originally told the residents.[8][9] Workers from the industry have admitted that there are a multitude of hidden mercury containers near the Wabigoon River that has caused health problems among the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation community to be a continuous issue.[12][11] The waste from the industry upstream has not merely affected the Wabigoon River system, the mercury contamination has also infected water sources that the Wabigoon River system feeds into such as Clay Lake and Ed Wilson Landing.[7] Additionally, the chemical waste from the industry in Dryden has impacted the health of the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation peoples, as well as the Wabaseemoong First Nation community (Wabaseemoong Independent Nations) further downstream.[13][14]

The mercury poisoning among the two First Nations communities were possible due to the lax laws regarding environmental pollution.[8] The former spokesman for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Chris Bentley claimed that the policies pertaining to the environment have since been amended to prevent occurrences like the disposal of mercury by the pulp and paper industry in Dryden.[8]

Conversely, the mercury contamination by the pulp and paper industry may be defined as environmental racism.[8][15]

The Ontario provincial government has initially told the First Nation community to stop eating fish — their main source of protein — and closed down their commercial fishery.[3] In 90%+ unemployment rate in 1970, closing of the commercial fishery meant economic disaster for the Indian reserve.[16][17] In other words, the closure of the fishery affected the once-booming tourism industry, where locals acted as guides for out of town fisherman.[16] Ivy Keewatin claimed that on the guided tours that she once conducted, she would take the attendees to a particular area in order to eat deep-fried pickerel (walleye).[16] That being said, it is due to the fact that the soil in the river and the sediment contains high levels of mercury that the fish in the Wabigoon River system may no longer be safely be ingested.[7] Therefore, it is because the Indigenous guides did not feel comfortable suggesting that tourists eat the fish contaminated with mercury and because the tourists did not wish to ingest fish with high levels of mercury that the fishing tourist industry no longer exists in the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation community.[16]

Grassy Narrows First Nation received a settlement in 1985 from the Government of Canada and the Reed Paper Company that bought-out the Dryden Pulp and Paper Company and its sister-company Dryden Chemical Company.[18][19] Moreover, in June 2017, the Ontario government pledged $85 million to clean up the industrial mercury contamination.[20] However, the mercury was never removed from the water and continues to affect the health of Grassy Narrows residents.[21] Government agencies responsible for the cleanup and study of the mercury pollution in the Wabigoon River system fear that dredging the sediments in the Wabigoon River may increase the levels of mercury downstream.[22] Thus, it is because the government entities do not wish to pollute the Wabigoon River system furthermore that the lack of cleanup is strategic rather than malicious.[22]

The amount of mercury present in fish as of 2012 was low according to Health Canada, that being said, a health advisory still remains in effect.[7][23] Consumption of fish continues in the area, particularly pickerel (walleye), the local favourite, but it is high on the food chain and therefore contains high levels of mercury.[21] Walleye remains dangerous for those with long-term exposure to the consumption of the fish as walleye contains approximately 13-15 times the recommended levels of mercury.[21][14] In particular, it is because the walleye are roughly 40-90 times the advisable mercury intake limit for pregnant women, children and women who hope to bear offspring that the walleye is predominately hazardous.[7] Some of the health issues associated with the consumption of the mercury infested fish in the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation community includes numbness, hearing loss, headaches, dizziness and limb cramps.[16] Additionally, studies have found that the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation have experienced hypertension, stroke, as well as lung, stomach, psychiatric, orthopedic and heart diseases due to eating fish with high levels of mercury.[14] Though there have been obvious health issues associated with the consumption of fish from the Wabigoon River system, Ed Wilson Landing, and Clay Lake, the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation community continue to eat the fish from these bodies of water as the community cannot afford to obtain boats in order to fish farther away from the infected waterways or afford pricey groceries.[7][24]

Ultimately, while the socioeconomic status of the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation people partially explains why the First Nation group still consumes the mercury-infested fish, the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation culture also contributes to the ingestion of fish by the Indigenous group.[7][24][25] According to First Nations people, fish is one of the healthiest substances that can be consumed.[25] Additionally, Indigenous people believe that people may learn from fish and learn cultural practices by fishing.[25] Given these points, the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation community have not stopped consuming fish as fish are considered as sacred more-than-human beings who have the ability to teach valuable lessons to the future generations.[25][7]

Timber extraction

On September 8, 2007, Ontario announced that it "had agreed to begin discussions with Grassy Narrows First Nation on forestry-related issues."[26] The provincial government appointed former Supreme Court of Canada and Federal Court of Canada Chief Justice Frank Iacobucci to lead these discussions.[26] Iacobucci's discussions with Grassy Narrows would focus on, "sustainable forest management partnership models and other forestry-related matters, including harvesting methods, interim protection for traditional activities and economic development."[26]

The reserve's other environmental concern is the mass extraction of trees for paper. Abitibi-Consolidated has been harvesting trees in the area. Local protestors have complained to the company and the Ministry of Natural Resources to demand a selective process. The community fears mass logging will lead to damage to local habitat.[27]

On August 17, 2011, First Nation supporters won a victory in court, when "Ontario's Superior Court ruled that the province cannot authorize timber and logging if the operations infringe on federal treaty promises protecting aboriginal rights to traditional hunting and trapping." [28] There were no immediate injunctions issued to stop logging activity, however.

In December 2014, a request for an individual environmental assessment into the impact of clear-cut logging was denied by the province.[29] Later released documents, after freedom of information requests, revealed concerns by local biologists that were never followed up on.[30]

Local services and transportation

The reserve is connected to areas beyond by local roads connecting with Highway 671. This highway provides connection to Kenora, 68.7 km (42.7 mi) to the south.

The closest airport is Kenora Airport and provides connections to other large communities including Thunder Bay and Winnipeg.

The reserve has one school, Sakatcheway Anishinabe School, the serves students from junior kindergarten to grade 12. From 1876 to 1969 McIntosh Indian Residential School was the closest school in McIntosh, Ontario.

A medical centre provides basic health care to residents and open Monday to Friday.[31] There is no hospital on the reserve; thus, more advanced care requires transfers to Kenora.

Treaty Three Police Service provides policing for the reserve

References

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census English River 21, Indian reserve [Census subdivision], Ontario and Kenora, District [Census division], Ontario". 2011 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. February 28, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Registered Population Official Name Grassy Narrows First Nation 149

- Anastasia M. Shkilnyk (March 11, 1985). A Poison Stronger than Love: The Destruction of an Ojibwa Community (trade paperback). Yale University Press. pp. 199–202. ISBN 978-0300033250.

- "Treaty 3 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux Tribe of the Ojibbeway Indians at the Northwest Angle on the Lake of the Woods with Adhesions" (ORDER IN COUNCIL SETTING UP COMMISSION FOR TREATY 3). Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. 1871. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- Anastasia M. Shkilnyk (March 11, 1985). A Poison Stronger than Love: The Destruction of an Ojibwa Community (trade paperback). Yale University Press. pp. 60 to 63 and succeeding chapters. ISBN 978-0300033250.

- Chapeskie, Andrew; Davidson-Hunt, Iain J.; Fobister, Roger (June 10–14, 1998). "Passing on Ojibway Lifeways in a Contemporary Environment" (conference paper). Digital Library of the Commons. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Poisson, Jayme; Bruser, David (November 23, 2016). "Grassy Narrows residents eating fish with highest mercury levels in province". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Bruser, David; Poisson, Jayme (November 11, 2017). "Ontario knew about Grassy Narrows mercury site for decades, but kept it secret". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- Hutchison, George (1977). Grassy Narrows. Photography by Dick Wallace. Toronto: Van Nostrand Reinhold. pp. 56. ISBN 9780442298777. OCLC 3356787.

- Mosa, Adam; Duffin, Jacalyn (February 6, 2017). "The interwoven history of mercury poisoning in Ontario and Japan". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 189 (5): E213–E215. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160943. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 5289874. PMID 27920011.

- Poisson, Jayme; Bruser, David (June 20, 2016). "Province ignores information about possible mercury dumping ground: Star Investigation". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- Porter, Jody (June 20, 2016). "Former Dryden, Ont. mill worker recalls dumping barrels of mercury in plastic-lined pit". CBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- Troian, Martha (September 20, 2016). "Neurological and birth defects haunt Wabaseemoong First Nation, decades after mercury dumping". CBC News. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- Takaoka, Shigeru; Fujino, Tadashi; Hotta, Nobuyuki; Ueda, Keishi; Hanada, Masanobu; Tajiri, Masami; Inoue, Yukari (2014). "Signs and symptoms of methylmercury contamination in a First Nations community in Northwestern Ontario, Canada". Science of the Total Environment. 468–469: 950–957. Bibcode:2014ScTEn.468..950T. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.09.015. PMID 24091119.

- Holifield, Ryan (2001). "Defining Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism". Urban Geography. 22: 78–90. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.22.1.78.

- Rodgers, Bob; Keewatin, Ivy (2009). "Return to grassy narrows: a poisoned community tells its 40-year-old story". Literary Review of Canada. 17 (1): 22–23 – via Academic OneFile.

- Leslie, Keith (March 24, 2017). "90% of Grassy Narrows residents show mercury poisoning signs: researchers". Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- "Free Grassy » Canada's Grassy Narrows First Nation demands government action after 50 years of mercury poisoning". freegrassy.net. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- Talaga, Tanya (July 28, 2014). "Report on mercury poisoning never shared, Grassy Narrows leaders say". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- Porter, Jody. "Ontario announces $85M to clean up mercury near Grassy Narrows, Wabaseemoong First Nations". CBC. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- "Mercury poisoning effects continue at Grassy Narrows: Mercury dumping halted in 1970 but symptoms persist". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. CBC News. June 4, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- "Draft Director's Order: Domtar Order" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- "Fact Sheet: Mercury Poisoning of the Grassy Narrows and White Dog Communities" (PDF). Free Grassy Narrows. December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- Vecsey, Christopher (1987). "Grassy Narrows Reserve: Mercury Pollution, Social Disruption, and Natural Resources: A Question of Autonomy". American Indian Quarterly. 11 (4): 287–314. doi:10.2307/1184289. JSTOR 1184289.

- Sewepagaham, Sherryl; Tailfeathers, Olivia (December 18, 2017). "Celebrating Canada's Indigenous Peoples Through Song and Dance: Music Alive Program Teacher's Guide" (PDF). ArtsAlive. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "ONTARIO ENTERS INTO FORESTRY DISCUSSIONS WITH GRASSY NARROWS". Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved December 17, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Grassy Narrows Fights for their Future". Archived from the original on March 11, 2010.

- "First Nation wins legal battle over clear-cutting". Cbc.ca. August 17, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- "Ontario gives green light to clear-cutting at Grassy Narrows". Toronto Star. December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- "Ontario's biologists called clear-cut logging plan 'big step backwards'". Toronto Star. January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- "Grassy Narrows First Nation, Grassy Narrows Medical Centre, Medical Centre".

External links

- Grassy Narrows First Nation at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- Grassy Narrows at Chiefs of Ontario

- "Passing Ojibway Lifeways in a Contemporary Environment"

Further reading

- Anestasia Shkilnyk, A Poison Stronger than Love: The Destruction of an Ojibwa Community, Yale University Press (March 11, 1985), trade paperback, 276 pages, ISBN 0300033257 ISBN 978-0300033250; hardcover, Yale University Press (March 11, 1985), ISBN 0300029977 ISBN 978-0300029970