Astrogliosis

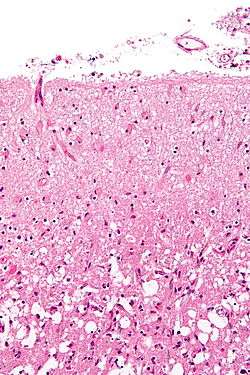

Astrogliosis (also known as astrocytosis or referred to as reactive astrocytosis) is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons from central nervous system (CNS) trauma, infection, ischemia, stroke, autoimmune responses or neurodegenerative disease. In healthy neural tissue, astrocytes play critical roles in energy provision, regulation of blood flow, homeostasis of extracellular fluid, homeostasis of ions and transmitters, regulation of synapse function and synaptic remodeling.[1][2] Astrogliosis changes the molecular expression and morphology of astrocytes, causing scar formation and, in severe cases, inhibition of axon regeneration.[3][4]

| Astrogliosis | |

|---|---|

Formation of reactive astrocytes after central nervous system (CNS) injury | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Causes

Reactive astrogliosis is a spectrum of changes in astrocytes that occur in response to all forms of CNS injury and disease. Changes due to reactive astrogliosis vary with the severity of the CNS insult along a graduated continuum of progressive alterations in molecular expression, progressive cellular hypertrophy, proliferation and scar formation.[3]

Insults to neurons in the central nervous system caused by infection, trauma, ischemia, stroke, autoimmune responses, or other neurodegenerative diseases may cause reactive astrocytes.[2]

When the astrogliosis is pathological itself, instead of a normal response to a pathological problem, it is referred to as astrocytopathy.[5]

Functions and effects

Reactive astrocytes may benefit or harm surrounding neural and non-neural cells. They undergo a series of changes that may alter astrocyte activities through gain or loss of functions lending to neural protection and repair, glial scarring, and regulation of CNS inflammation.

Neural protection and repair

Proliferating reactive astrocytes are critical to scar formation and function to reduce the spread and persistence of inflammatory cells, to maintain the repair of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), to decrease tissue damage and lesion size, and to decrease neuronal loss and demyelination.[6][7]

Reactive astrocytes defend against oxidative stress through glutathione production and have the responsibility of protecting CNS cells from NH4+ toxicity.[3] They protect CNS cells and tissue through various methods,[3][8][9] such as uptake of potentially excitotoxic glutamate, adenosine release, and degradation of amyloid β peptides.[3] The repair of a disruption in the blood brain barrier is also facilitated by reactive astrocytes by their direct endfeet (characteristic structure of astrocytes) interaction with blood vessel walls that induce blood brain barrier properties.[8]

They have also been shown to reduce vasogenic edema after trauma, stroke, or obstructive hydrocephalus.[3]

Scar formation

Proliferating reactive scar-forming astrocytes are consistently found along borders between healthy tissues and pockets of damaged tissue and inflammatory cells. This is usually found after a rapid, locally triggered inflammatory response to acute traumatic injury in the spinal cord and brain. In its extreme form, reactive astrogliosis can lead to the appearance of newly proliferated astrocytes and scar formation in response to severe tissue damage or inflammation.

Molecular triggers that lead to this scar formation include epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), endothelin 1 and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mature astrocytes can re-enter the cell cycle and proliferate during scar formation. Some proliferating reactive astrocytes can derive from NG2 progenitor cells in the local parenchyma from ependymal cell progenitors after injury or stroke. There are also multipotent progenitors in subependymal tissue that express glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and generate progeny cells that migrate towards sites of injury after trauma or stroke.[10]

Regulation of inflammation

Reactive astrocytes are related to the normal function of astrocytes. Astrocytes are involved in the complex regulation of CNS inflammation that is likely to be context-dependent and regulated by multimodal extra- and intracellular signaling events. They have the capacity to make different types of molecules with either pro- or anti-inflammatory potential in response to different types of stimulation. Astrocytes interact extensively with microglia and play a key role in CNS inflammation. Reactive astrocytes can then lead to abnormal function of astrocytes and affect their regulation and response to inflammation.[10][11]

Pertaining to anti-inflammatory effects, reactive scar-forming astrocytes help reduce the spread of inflammatory cells during locally initiated inflammatory responses to traumatic injury or during peripherally-initiated adaptive immune responses.[3][8] In regard to pro-inflammatory potential, certain molecules in astrocytes are associated with an increase in inflammation after traumatic injury.[3]

At early stages after insults, astrocytes not only activate inflammation, but also form potent cell migration barriers over time. These barriers mark areas where intense inflammation is needed and restrict the spread of inflammatory cells and infectious agents to nearby healthy tissue.[3][7][8] CNS injury responses have favored mechanisms that keep small injuries uninfected. Inhibition of the migration of inflammatory cells and infectious agents have led to the accidental byproduct of axon regeneration inhibition, owing to the redundancy between migration cues across cell types.[3][7]

Biological mechanisms

Changes resulting from astrogliosis are regulated in a context-specific manner by specific signaling events that have the potential to modify both the nature and degree of these changes. Under different conditions of stimulation, astrocytes can produce intercellular effector molecules that alter the expression of molecules in cellular activities of cell structure, energy metabolism, intracellular signaling, and membrane transporters and pumps.[10][12] Reactive astrocytes respond according to different signals and impact neuronal function. Molecular mediators are released by neurons, microglia, oligodendrocyte lineage cells, endothelia, leukocytes, and other astrocytes in the CNS tissue in response to insults ranging from subtle cellular perturbations to intense tissue injury.[3] The resulting effects can range from blood flow regulation to provision of energy to synaptic function and neural plasticity.

.tif.jpg)

Signaling molecules

Few of the known signaling molecules and their effects are understood in the context of reactive astrocytes responding to different degrees of insult.

Upregulation of GFAP, which is induced by FGF, TGFB, and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), is a classic marker for reactive gliosis.[2][13] Axon regeneration does not occur in areas with an increase in GFAP and vimentin. Paradoxically, an increase in GFAP production is also specific to the minimization of the lesion size and reduction in the risk for autoimmune encephalomyelitis and stroke.[13]

Transporters and channels

The presence of astrocyte glutamate transporters is associated with a reduced number of seizures and diminished neurodegeneration whereas the astrocyte gap junction protein Cx43 contributes to the neuroprotective effect of preconditioning to hypoxia. In addition, AQP4, an astrocyte water channel, plays a crucial role in cytotoxic edema and aggravate outcome after stroke.[3]

Neurological pathologies

Loss or disturbance of functions normally performed by astrocytes or reactive astrocytes during the process of reactive astrogliosis has the potential to underlie neural dysfunction and pathology in various conditions including trauma, stroke, multiple sclerosis, and others. Some of the examples are as follows:[3]

- Autoimmune destruction of astrocyte endfeet that contact and envelop blood vessels is associated with CNS inflammation and a form of multiple sclerosis

- Rasmussen's syndrome autoantibody destruction of astrocytes causes seizures

- In Alexander's disease, a dominant, gain-of-function mutation of the gene encoding GFAP is associated with macro-encephalopathy, seizures, psychomotor disturbances, and premature death.

- In a familial form of amyotropic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a dominant gain-of-function mutation of the gene encoding superoxide dismutase (SOD) leads to production of reactive astrocytes of molecules that are toxic to motor neurons.

Reactive astrocytes may also be stimulated by specific signaling cascades to gain detrimental effects such as the following:[3][14]

- Exacerbation of inflammation via cytokine production

- Production and release of neurotoxic levels of reactive oxygen species

- Release of potentially excitotoxic glutamate

- The potential contribution to seizure genesis

- Compromise of blood-brain barrier function as a result of vascular endothelial growth factor production

- Cytotoxic edema during trauma and stroke through AQP4 overactivity

- Potential for chronic cytokine activation of astrocytes to contribute to chronic pain

Reactive astrocytes have the potential to promote neural toxicity via the generation cytotoxic molecules such as nitric oxide radicals and other reactive oxygen species,[7] which may damage nearby neurons. Reactive astrocytes may also promote secondary degeneration after CNS injury.[7]

Novel therapeutic techniques

Due to the destructive effects of astrogliosis, which include altered molecular expression, release of inflammatory factors, astrocyte proliferation and neuronal dysfunction, researchers are currently searching for new ways to treat astrogliosis and neurodegenerative diseases. Various studies have shown the role of astrocytes in diseases such as Alzheimer's, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's, and Huntington's.[15] The inflammation caused by reactive astrogliosis augments many of these neurological diseases.[16] Current studies are researching the possible benefits of inhibiting the inflammation caused by reactive gliosis in order to reduce its neurotoxic effects.

Neurotrophins are currently being researched as possible drugs for neuronal protection, as they have been shown to restore neuronal function. For example, a few studies have used nerve growth factors to regain some cholinergic function in patients with Alzheimer's.[15]

Anti-gliosis function of BB14

One specific drug candidate is BB14, which is a nerve growth factor-like peptide that acts as a TrkA agonist.[15] BB14 was shown to reduce reactive astrogliosis following peripheral nerve injuries in rats by acting on DRG and PC12 cell differentiation.[15] Although further research is needed, BB14 has the potential to treat a variety neurological diseases. Further research of neurotrophins could potentially lead to the development of a highly selective, potent, and small neurotrophin that targets reactive gliosis to alleviate some neurodegenerative diseases.

Regulatory function of TGFB

TGFB is a regulatory molecule involved in proteoglycan production. This production is increased in the presence of bFGF or Interleukin 1. An anti-TGFβ antibody may potentially reduce GFAP upregulation after CNS injuries, promoting axonal regeneration.[2]

Ethidium bromide treatment

Injection of ethidium bromide kills all CNS glia (oligodendrocytes and astrocytes), but leaves axons, blood vessels, and macrophages unaffected.[2][4] This provides an environment conducive to axonal regeneration for about four days. After four days, CNS glia reinvade the area of injection and axonal regeneration is consequently inhibited.[2] This method has been shown to reduce glial scarring following CNS trauma.[4]

Metalloprotinease activity

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells and C6 glioma cells produce metalloproteinase, which is shown to inactivate a type of inhibitory proteoglycan secreted by Schwann cells. Consequently, increased metalloproteinase in the environment around axons may facilitate axonal regeneration via degradation of inhibitory molecules due to increased proteolytic activity.[2]

References

- Gordon, Grant R. J.; Mulligan, Sean J.; MacVicar, Brian A. (2007). "Astrocyte control of the cerebrovasculature". Glia. 55 (12): 1214–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.477.3137. doi:10.1002/glia.20543. PMID 17659528.

- Fawcett, James W; Asher, Richard.A (1999). "The glial scar and central nervous system repair". Brain Research Bulletin. 49 (6): 377–91. doi:10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00072-6. PMID 10483914.

- Sofroniew, Michael V. (2009). "Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation". Trends in Neurosciences. 32 (12): 638–47. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. PMC 2787735. PMID 19782411.

- McGraw, J.; Hiebert, G.W.; Steeves, J.D. (2001). "Modulating astrogliosis after neurotrauma". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 63 (2): 109–15. doi:10.1002/1097-4547(20010115)63:2<109::AID-JNR1002>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID 11169620.

- Sofroniew Michael V (2014). "Astrogliosis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (2): a020420. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020420.

- Barres, B (2008). "The Mystery and Magic of Glia: A Perspective on Their Roles in Health and Disease". Neuron. 60 (3): 430–40. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. PMID 18995817.

- Sofroniew, M. V. (2005). "Reactive Astrocytes in Neural Repair and Protection". The Neuroscientist. 11 (5): 400–7. doi:10.1177/1073858405278321. PMID 16151042.

- Bush, T; Puvanachandra, N; Horner, C; Polito, A; Ostenfeld, T; Svendsen, C; Mucke, L; Johnson, M; Sofroniew, M (1999). "Leukocyte Infiltration, Neuronal Degeneration, and Neurite Outgrowth after Ablation of Scar-Forming, Reactive Astrocytes in Adult Transgenic Mice". Neuron. 23 (2): 297–308. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80781-3. PMID 10399936.

- Zador, Zsolt; Stiver, Shirley; Wang, Vincent; Manley, Geoffrey T. (2009). "Role of Aquaporin-4 in Cerebral Edema and Stroke". In Beitz, Eric (ed.). Aquaporins. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 190. pp. 159–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-79885-9_7. ISBN 978-3-540-79884-2. PMC 3516842. PMID 19096776.

- Eddleston, M.; Mucke, L. (1993). "Molecular profile of reactive astrocytes—Implications for their role in neurologic disease". Neuroscience. 54 (1): 15–36. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(93)90380-X. PMC 7130906. PMID 8515840.

- Farina, Cinthia; Aloisi, Francesca; Meinl, Edgar (2007). "Astrocytes are active players in cerebral innate immunity". Trends in Immunology. 28 (3): 138–45. doi:10.1016/j.it.2007.01.005. PMID 17276138.

- John, Gareth R.; Lee, Sunhee C.; Song, Xianyuan; Rivieccio, Mark; Brosnan, Celia F. (2005). "IL-1-regulated responses in astrocytes: Relevance to injury and recovery". Glia. 49 (2): 161–76. doi:10.1002/glia.20109. PMID 15472994.

- Pekny, Milos; Nilsson, Michael (2005). "Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis". Glia. 50 (4): 427–34. doi:10.1002/glia.20207. PMID 15846805.

- Milligan, Erin D.; Watkins, Linda R. (2009). "Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1038/nrn2533. PMC 2752436. PMID 19096368.

- Colangelo, Anna Maria; Cirillo, Giovanni; Lavitrano, Maria Luisa; Alberghina, Lilia; Papa, Michele (2012). "Targeting reactive astrogliosis by novel biotechnological strategies". Biotechnology Advances. 30 (1): 261–71. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.06.016. PMID 21763415.

- Mrak, Robert E.; Griffin, W. Sue T. (2005). "Glia and their cytokines in progression of neurodegeneration". Neurobiology of Aging. 26 (3): 349–54. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.010. PMID 15639313.