Askøy Bridge

The Askøy Bridge (Norwegian: Askøybroen) is a suspension bridge which crosses the Byfjorden between the municipalities of Bergen and Askøy in Vestland county, Norway. It is 1,057 meters (3,468 ft) long and has a main span of 850 meters (2,789 ft). Its span was the longest for any suspension bridge in Norway, until the Hardanger Bridge was opened in August 2013. It carries two lanes of County Road 562 and a combined pedestrian and bicycle path. The bridge's two concrete pylons are 152 meters (499 ft) tall and are located at Brøstadneset in Bergen municipality (on the Bergen Peninsula of the mainland) and Storeklubben in Askøy municipality (on the island of Askøy). The bridge has seven spans in total, although all but the main span are concrete viaducts. The bridge has a clearance below of 62 meters (203 ft).

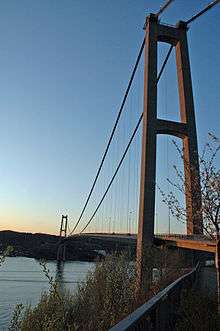

Askøy Bridge | |

|---|---|

The bridge seen from the mainland | |

| Coordinates | 60.3961°N 5.2142°E |

| Carries | Two lanes of County Road 562 Pedestrian/bicycle path |

| Crosses | Byfjorden |

| Locale | Bergen and Askøy, Norway |

| Official name | Askøybroen |

| Maintained by | Norwegian Public Roads Administration |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge |

| Total length | 1,057 m (3,468 ft)[1] |

| Width | 15.5 m (51 ft)[1] |

| Height | 152 m (499 ft)[1] |

| Longest span | 850 m (2,789 ft)[1] |

| Clearance below | 62 m (203 ft)[1] |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1989 |

| Construction end | 1992 |

| Opened | 12 December 1992 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 17,251[2] |

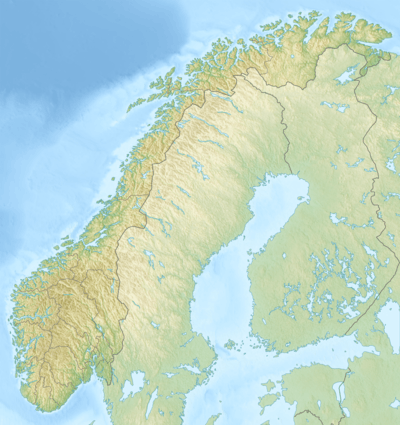

Askøy Bridge Location in Norway | |

The first plans to replace the Kleppestø–Nøstet Ferry with a bridge, which would allow the island of Askøy to have a fixed link, was launched in the 1960s. Various proposals were made, including placing the bridge further east and closer to Bergen, and building a submerged floating tunnel. In the early 1970s, a toll company was established to finance the bridge, but the planned costs were too high to cover with just tolls and there was the lack of a motorway to Bergen from the west. Because of this, the construction of the bridge was postponed. In the early 1980s, there was controversy about whether advanced tolls should be charged on the ferry, but these were ultimately charged from 1984 until the bridge opened. Construction started in 1989 and the bridge opened ahead of schedule on 12 December 1992, along with a new section of the road which included the Stongafjell Tunnel and Olsvik Tunnel. The bridge remained a toll road until 2006.

Specifications

The bridge is a 1,056.7 meters (3,467 ft) long suspension bridge with a main span of 850 meters (2,790 ft). It has two concrete pylons, each 149.5 meters (490 ft), albeit 152 meters (499 ft) tall when including the mounts for the suspension cable. The pylons are 4.5 meters (15 ft) wide and vary in width between 13.75 meters (45.1 ft) at the top to 21.0 meters (68.9 ft) at the bottom. They pylons have three horizontal connectors, one under the deck at 56.4 meters (185 ft), one at 102.2 meters (335 ft) and one at the top.[3] The bridge has seven spans, with all but the main spans being concrete viaducts, and thus not connected to the suspension cable. The aerodynamic closed bridge girder has a vertical radius of 9,000 meters (30,000 ft), a height of 3.0 meters (9.8 ft) and a width of 15.5 meters (51 ft).[1] The bridge deck is 13.75 meters (45.1 ft) wide; each of the two main lanes are 4.36 meters (14.3 ft) wide, while the pedestrian and bicycle path is 3.45 meters (11.3 ft) wide. The bridge can be reconfigured to instead carry three lanes, with a new bicycle and pedestrian path being mounted on the side.[3]

There are two main cables, one on each side, which consist of twenty locked coil cables in a seven wide and three tall matrix. Each strand has a diameter of 99 millimeters (3.9 in). The cable has a quality of 1,570 megapascals.[1] Each coil, which consists of 289 wires, can tolerate at least 9,060 kilonewtons (2,040,000 lbf) and weighs 71 tonnes (70 long tons; 78 short tons). The cables are anchored in rock 35 meters (115 ft) below the road level.[3] The main span's sag-to-span ratio is 1:10.[1] The bridge has a 200-meter (660 ft) wide clearance below of 62 meters (203 ft).[3] The bridge carries two lanes of County Road 562 across Byfjorden, between Storeklubben in Askøy and Brøstaneset in Bergen.[4] In 2010, the bridge had an average traffic of 17,251 vehicles per day.[2]

History

.jpg)

Proposals and planning

The first official discussion of a bridge from the mainland to Askøy was on 15 December 1960, when municipal councilor Alf Fagerli took up the issue in the municipal council based on the plans for the Sotra Bridge, which would create a fixed link for Sotra to the mainland.[5] The council asked Engineer Caspar Trumpy to make proposals for a bridge. It was followed by a public meeting on 8 March 1961 in Laksevåg, where the transport for the areas west of Bergen, Laksevåg, Sotra and Askøy, was discussed.[6] On 8 September the municipal council considered Trumpy's five proposals, which varied in cost from 62 to 103 million kr. Four of the proposals ran to Kvarven, while one proposal went from Storeklubben to Bøstadneset. All would require additional roads on both sides.[7] To follow up the proposals, the municipality established a bridge committee on 30 November 1961, which was chaired by Mayor Olav Bjørkaas and with Johan Sørensen as deputy chair.[8]

The committee presented its conclusions to the municipal council on 8 December 1966: they felt it would be economically feasible to have the bridge completed by 1975, that it should be built between Storeklubben and Brøstadneset, and that it was necessary to establish a toll company to finance part of the bridge.[9] The chief-of-administration commented that the estimates had only vague guesses at the frequency at which people would use the bridge and that if these fell short the toll company would have large losses which would have to be covered by the municipality. There was also a discussion as to whether ferry should be kept, but as a passenger-only service.[10] Estimates also showed that travel time from Askøy to Bergen would remain the same as with the ferry, and that few people would use cars to work with the prospected tolls.[11] The council voted with 35 against 8 votes to support the proposal from the committee.[12] Additional plans from Trumpy for the bridge were presented in 1969, this time also including proposals for both a two-lane and four-lane bridge. The latter would increase the costs with 10 million kr. At the time the bridge was estimated to cost 57 million kr.[13]

Because of the depth of Byfjorden, which reaches 320 meters (1,050 ft) below mean sea level, Trumpy had not looked into a conventional subsea tunnel. However, he had instead considered a submerged floating tunnel, but concluded that it was unrealistic, in part because of the anchoring depth, in part because of the strong current and in part because no such tunnel had ever been built.[14] On 21 March 1969, Engineer Per Tveit held a lecture in Bergen, where he projected that a tunnel to Askøy at Kvarnen would cost NOK 28 million.[15] Trumpy estimated the cost of the tunnel, which would be 900 meters (3,000 ft) in water and 1,750 meters (5,740 ft) to NOK 150 million.[16] In 1970, modified plans were launched for a submerged tunnel which instead of being anchored in the seabed instead was horizontally suspended at each end in bedrock.[17]

On 12 November 1970, the municipal council voted to establish a limited company to finance the bridge.[18] Askøybrua AS was founded with a share capital of NOK 775,000 and owned by the municipalities of Askøy, Laksevåg, Åsane, Fjell, Sund and Øygarden, Hordaland County Municipality and Rutelaget Askøy–Bergen—the latter who operated all the islands bus routes and the ferry.[19] During the council meeting, representatives for the municipal administration commented that 85 percent of the people from Askøy who worked outside the municipality worked in the city center of Bergen; they were transported quickly with ferries which were not hampered by congestion. Should a bridge be built, it would only be able to be financed if people traveled using the bridge, and therefore terminating the ferry, even though it provided a superior service, was proposed.[20]

The plans and financing estimates for the bridge were sent to the Norwegian Public Roads Administration on 7 July 1972, who from then took the leading role in planning the bridge. The administration stated the same month that they intended to work on the plans for the bridge between Storeklubben and Brøstadneset.[21] In 1974, the administration stated that they would pay for maintenance of the bridge and auxiliary roads, which would save the toll company NOK 700,000 per year.[22]

Bergen Municipality, which merged with the surrounding municipalities of Arna, Åsane, Fana, and Laksevåg on 1 January 1972, was skeptical to the plans for a new bridge. They were concerned that additional cars and buses would clog up the city center additionally. The issue about joining the toll company was placed on hold within Bergen Municipality, and without Bergen signing for the required shares, the company could not be established.[23] Not until 5 November 1973 did Bergen Municipal Council vote to purchase the shares in the company.[21] This was in part motivated by a report that showed that 46% of the traffic on the ferry was going to places south and west of the city center—traffic which would not contribute to congestion with a bridge. The company was officially founded on 14 March 1974 with Bjørkaas being appointed chair and Sørensen deputy chair.[24] They would both remain in these positions until 1993.[25][26]

After the proposals for a tunnel died out in 1970, there remained two critical groups against the project: those who were in favor of the bridge, but critical to the details in the plan, and those who were opposed to a bridge and wanted to keep the ferry service. The former group was largely concerned about the choice of the outer route, rather than the inner crossing to Kvarven. The latter would give a significantly shorter route to the city center, and the same driving distance to places south of Bergen, including Bergen Airport, Flesland.[27] Another issue was that there was not a sufficient road network in Bergen to handle the traffic from the bridge.[28] Starting in late 1970, a petition was created demanding a referendum about which crossing should be chosen.[29] The issue was discussed in the municipal council on 23 April,[30] and was dismissed with five votes in favor of a referendum.[31]

Inflation during the early 1970s increased the cost estimates for a four-lane bridge to NOK 120 million in 1974, and to NOK 166 million including auxiliary roads. In 1976, the Public Roads Administration proposed that the bridge be built with two lanes and a pedestrian and bicycle path which later could be converted to a third lane.[32] On 6 June 1977, the toll company sent an application to the county asking for how much county and state grants they could get for the bridge, and if it would be possible for the county to guarantee for the loan. The company stated that they felt they should receive the same conditions as the by then completed Sotra Bridge, where they state had paid for the auxiliary roads and a third of the bridge. The company offered to advance most of the state's grants, and receive them back in a period of twelve years. The plans at the time involved connecting the bridge to the existing county road at Kjøkkelvik and use it onwards to Loddefjord.[33]

In 1976, a proposal was made to established a new ferry service from Kleppestø to Kjøkkelvik on the mainland. This would provide a shorter ferry ride and shorter transport for vehicles heading to western Bergen. The idea was passed by Askøy Municipal Council on 26 August 1976, and was also supported by Bergen's executive committee. However, there were large protests from locals in Kjøkkelvik and Kjøkkelvikdalen.[34] The Public Roads Administration proposed two plans for a ferry service in 1979, one to Kjøkkelvik and one further east at Kvarven, which would have to run via a tunnel to the southern end of Gravdalsvatnet, where it could intersect with National Road 555. The latter would be able to take over all transport between Askøy and Bergen, leaving the ferry service to Nøstet to only have passenger transport. To ease local protests in Kjøkkelvik, Rutelaget bought a property east of Brøstadneset in 1980. The Kvarven proposal was opposed by the Norwegian Armed Forces, who had installations in the area, and the Norwegian Diver School, which had established itself at Gravdal in 1980.[35] Because of the opposition, Askøy Municipal Council on 26 August 1982 voted to instead work to upgrade the ferry quay at Nøstet.[36]

In 1977, the debate about the ferry arose again. The bridge would necessarily terminate the car ferry service, but many locals wanted to keep a passenger ferry, which would provide faster service between Bergen and Kleppestø than the buses could.[37] A public meeting held on 1 November 1977 established the Information Panel For the Askøy Bridge which demanded that the bridge not yet be built and the ferry service remain.[38] Within a week they presented a report to the county municipality's transport committee, but were not able to convince the committee to instruct the toll company to work to retain a passenger ferry service. Protests were also made by parents at Lyderhorn School and Nybø School in Bergen, which were both located along the roads which were proposed used to connect to the bridge.[39] The issue was discussed in the county council on 14 December.[40] The council voted principally in favor of a bridge, but did not give any grants. It also did not prioritize between the Askøy Bridge and the planned Nordhordland Bridge.[41]

Two days later, Einar Corneliussen, director of the Bergen Port Authority, stated that they had erred when they had permitted the Sotra Bridge to be built with a clearance below of 50 meters (160 ft), after abandoning their original demands of 60 meters (200 ft), and that large ships now had to sail around Hjeltefjorden. Although Bergen Mekaniske Verksted (BMV) previously had accepted a height of 60 meters (200 ft), that was in a time when drilling rigs could have their towers lowered, which was no longer the case. Corneliusen stated that the clearance on the Askøy Bridge would have to be at least 80 meters (260 ft).[41] The Public Roads Administration stated that this would increase the span with 70 meters (230 ft).[42] On 13 September 1978, Bergen Municipality stated that their official stand was that the bridge had to have a clearance of 80 meters (260 ft).[43]

In 1978, Rutelaget Askøy–Bergen started planning possible bus routes from the island across the bridge, and also proposed purchasing new fast ferries which could run from Kleppestø to Nøsten in less than ten minutes. In September 1979, the Public Roads Administration presented the plans for a new road structure in Ytre Laksevåg along National Road 555, including a connection to the bridge, as well as the possibility for a new ferry quay. The plan had four main routes from the bridge towards the city center, and the bridge was planned with two clearances, 62 and 80 meters (203 and 262 ft).[44] The first alternative involved a tunnel from the bridge to Gravdalsvatnet, which would be the shortest route. The second would run part of the way to Gravdalsvatnet, where it would merge with National Road 555 and both would run through a tunnel to Gravdalsvatnet; this would give about the same distance to the city center, but shorter distance to Sotra. Alternative three involved the tunnel running southwards and intersecting with 555 at Loddefjord. Alternative four involved an even more western route, and would intersect at Storavatnet. Alternative four gave a 3.5 kilometers (2.2 mi) longer route to the city center than alternative one, but was regarded as the best technically and with the least environmental impact. The agency recommended the first or fourth proposal.[45]

Prior to the county council discussing the Norwegian Road Plan and the County Road Plan in 1979, the Public Roads Administration recommended that the Nordhordland Bridge should be prioritized before the Askøy Bridge, as the former would be part of the Coastal Highway. This would result in the Askøy Bridge being prioritized after 1989.[46] The priorities were seconded by the county council.[47]

In Askøy, the Labour Party, the Conservative Party and the Liberal People's Party were strongly in favor of the bridge, the Christian Democratic Party did not mention the issue in their program, the Liberal Party was in a similar limbo position, while the Socialist Left Party was opposed to the bridge.[48] The latter was particularly concerned about increased use of cars, increased travel time to Bergen and the environmental impact.[49] The Liberal Party was on their side not so much opposed to a bridge, as they felt it was unrealistic, all the time the necessary planning of a connection on the Bergen side was not being prioritized.[48]

Advanced toll controversy

In a letter dated 30 April 1982 to Mayor Kåre Minde, Kjell Kristensen and sixteen other former councilors from northern Askøy stated that they were not satisfied with the progress in the planning, and proposed that advanced tolls be placed on the ferry. The petition was supported by several other politicians, but was dismissed by Rutelaget Askøy–Bergen, who stated that the bridge plans not specific yet, that the ferry tickets were expensive enough as they were, and that many of the travelers with the ferry would continue to use it after the bridge came and would thus not have any use of the bridge, but yet pay for it.[50] Advanced tolls were supported by 33 against 7 votes in the municipal council on 24 June; the Socialist Left Party and some Liberal Party members were the only to oppose. However, the decisions had so many technical faults to it that the Public Roads Administration rejected it, commenting among other things that the decision presumed a bridge would be completed in 1988—which was not realistic. A new municipal decision was made in October, supporting the advanced tolls starting from 1983.[51]

Rolf Bech-Sørensen stated that advance tolls would be unfair, as it was taxation of people which would not receive the benefit and that it essentially would be taxation of commuting. He therefore proposed that a referendum about advanced tolls be held at the same time as the 1983 municipal election. The National Roads Administration stated that the advanced tolls would reduce the capital need for the bridge by NOK 30 million. State Secretary Karl-Wilhelm Sirkka of the Ministry of Transport and Communications stated that the ministry would in general approve advanced tolls if they had municipal and county support. The proposal was followed up by the county council without much debate.[52]

At their general assembly on 23 January 1983, Askøy Commuter Association unanimously supported the advanced tolls.[53] Bech-Sørensen stated that the commuter has been betrayed by their own organization and proposed that a new commuter association be established which would be opposed to the advanced tolls. This resulted in a petition being established against the advanced tolls, which gradually was formalized as the Action Against Advanced Tolls (AMF). Representatives for the movement stated that no parties had had advanced tolls in their party programs in the previous election, and that a referendum had been rejected by the council, and the people thus had not had a possibility to influence the issue.[54]

Johan Sørensen stated that it was necessary to have advanced tolls for the bridge to be included on the Norwegian Road Plan, but this was denied by the Ministry of Transport. They did, however, state that it would be easier to finance the bridge with save-up advanced tolls. By 26 April, 5,000 people had signed the petition against advanced toll. This caused the Liberal Party to take an active stance against advanced tolls.[55] By May the petition had 6,300 signatures, equal to more than half of those entitled to vote and two-thirds of the number of people who had voted in the previous municipal election. The issue became the major issue ahead of the election.[56] Both AMF and the toll company sent delegations to Oslo to speak with Minister of Transport and Communications Johan J. Jacobsen.[57] Because of the lack of opposition in the elected bodies, it was expected that the Parliament would pass the advanced tolls; however, Askøy's only parliamentarian, Mons Espelid from the Liberal Party, stated that he was opposed.[58]

Alv Nepstad, who was chair of Rutelaget Askøy–Bergen, board member in the toll company and councilor for the Progress Party, made an alternative proposal. Banks would issue a loan of NOK 50 million towards the bridge, guaranteed in the real estate in the municipality. This would require that the owners of all 12,120 properties on the island agree to the agreement, and that a judicial registration for each of those properties be made to secure a guarantee for NOK 4,125 each. Bjørkaas stated that the proposal did not involve any increased revenue for the bridge, and only would increase the company's debt. Sparebanken Vest characterized the idea as completely unrealistic and that the loan was planned taken up with a municipal and county guarantee anyway.[59]

Ahead of the municipal elections in September 1983, two parties, the Socialist Left and Liberal Parties, were clearly opposed to the advanced tolls, while two new parties, the Progress Party and Red Electoral Alliance, also were opposed. AMF therefore established a local list to run in the municipal election which would consist of members of the three parties which were in favor of the advanced tolls, the Labour, Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties.[60] The list won four seats, while the Progress Party captured three and the Socialist Left Party increased from one to two. However, the Liberal Party fell from nine to five representatives. The Labour Party did a good election, as they captured many votes from people north and west on Askøy, who were generally positive to the advanced tolls.[61]

As the new municipal council still had a majority in favor of advanced tolls, the proposal was passed by Parliament on 5 December.[61] The toll company was allowed to collect advanced tolls on the Kleppestø–Nøstet Ferry from 1 January 1984 to 1 January 1991. The money was only permitted used to plan the bridge's auxiliary roads on Askøy, consisting of the section from Krokåsskiftet to Storeklubben and on to Kleppestø. In 1982, this was estimated to cost NOK 30 million.[62]

Final planning

In 1984, BMV stated that new rig constructions demanded that 100 meters (330 ft) tall structures have access to the port, which would require a clearance below of 110 meters (360 ft). The demand was supported by the Bergen Port Authority board.[63] This would result in the pylons being over 200 meters (660 ft) tall, making them second only to Golden Gate Bridge in height. In 1985, the costs for the clearance alternatives was NOK 370 million for 62 meters (203 ft), NOK 400 million for 80 meters (260 ft) and NOK 470 million for 110 meters (360 ft). BMV proposed that a submersible floating tunnel be built, and estimated it to cost NOK 500 million.[64]

In response, the Public Road Administration proposed that tall rigs could sail to Bergen via Herdlafjorden, which is located on the east side of Askøy. While common for coastal ship traffic, there are two points which are too shallow for deep vessels, at Det NEue and herdlaflaket, where a 200-meter (660 ft) wide and 15 meters (49 ft) deep trench could be blasted out.[65] The operation was estimated to cost NOK 30 million, and would be cheaper than raising the clearance of the bridge. The toll company subsequently offered to cover the costs of the blasting and the port authority agreed to allow the bridge height be 62 meters (203 ft).[66]

Askøy Municipal Council voted on 26 August 1982 that they preferred that connection from the bridge to the city center to run via a tunnel from Kjøkkelvik to Gravdalsvatnet.[66] Bergen Municipality was concerned about that such a road would have a negative impact on the neighborhoods it would run through, and on 28 October 1985 voted for a tunnel from the bridge to Storavatnet and that a new highway would have to be built from there to the city center before the bridge be built.[67] Specifically this involved the construction of two new tunnels, the Lyderhorn Tunnel and the Damsgård Tunnel. The latter was part of the existing plans for road construction and was scheduled for completion in 1992. However, the Lyderhorn Tunnel would have to be pushed forward, as it was planned completed in 1996. The toll company offered to advance NOK 50 million of the necessary NOK 70 million that the tunnel costs, on condition that it be refunded in 1994 and 1995 and that Bergen Municipality pay half the interest costs. The proposal was passed by both municipalities.[68]

In 1982, a consortium consisting of Kristian Jebsens Rederi, BMV and Lau Eide made a proposal to borrow money privately abroad and hire Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries of Japan to build the bridge.[69] The proposal was rejected by the Public Roads Administration, who wanted to have an open tender to build the bridge, and wanted the project organized as a regular road construction administrated by themselves. The Public Roads Administration continued to work with a model which involved a foreign loan,[70] but eventually failed to receive permission from the Ministry of Finance. Instead the toll company started negotiating with domestic banks, and in September 1984 the company agreed to borrow up to 600 million 1983-NOK and 1.2 billion 1991-NOK, without public guarantees, from Den norske Creditbank (DnC) and Nevi.[71]

The toll company needed permission from the Ministry of Transport and Communications to establish a toll for the bridge, but they deemed the project so large that it would have to be voted over by Parliament. This required the company to document issues such as capital need, repayment, traffic estimates, which was first completed in April 1986. It was then processed by the Public Roads Administration. Parliament's Standing Committee on Transport and Communications visited Bergen on 29 October 1987.[72] Building of both the Askøy Bridge and the Nordhordland Bridge were passed by Parliament on 9 December. The Askøy Bridge was passed unanimously, but both the Progress Party and the Socialist Left Party voted to cease the collection of advanced tolls.[73]

The toll company was given the responsibility to finance the bridge, while the Public Roads Administration would be the builder and retain ownership of and maintenance of the bridge.[74] The agreement with DnC was made on 9 January 1989,[72] but Nevi had fallen into financial difficulties and the toll company feared it would not be able to meet its obligations. Nevi's new owner, Bergen Bank, was not willing to guarantee for the loan, and instead DnC offered to lend the entire capital. In March, the toll company contacted the Ministry of Transport to attempt to gain a state guarantee for the loan, which would result in a lower interest. This was rejected by the ministry on 18 April, and a similar application to the county was also rejected.[75]

National Road 555 has cost overruns of NOK 150 million and in 1989, the toll company offered to cover NOK 30 million of those on condition that they were refunded the capital between 1994 and 1996. John Sørensen was hired as managing director for the toll company from 1 July 1990; until then the work had been done by the board and consultants.[76]

Construction

Construction began on 24 April 1989.[77] This not only included work on the bridge itself, but also National Road 562 from the bridge at Storeklubben to Krokåsskiftet and National Road 563 from the bridge to Kleppestø in Askøy. On the Bergen side, work started at Storavatnet and on the Olsvik Tunnel on 1 June. The breakthrough in the tunnel was reached on 1 December, allowing it to function as a tote road. Work also commenced on National Road 555, including work at Liavatnet and Gravdalsvatnet, in addition to the construction of the Lyderhorn and Damsgård Tunnels. The work on the pylon on the Askøy side was completed in September and on 31 October the viaduct was completed. By the end of 1990, 210 people were working on construction of the bridge itself.[78]

Production of the suspension cables was done by Thyssen of Germany, while the vertical suspenders were built by Bridon Ropes in England. The 24 steel deck boxes were built by Kværner Eureka in Moss. The first wire of the suspension cable was placed between the pylons on 1 July 1991. The three auxiliary roads on Askøy were completed by December 1991.[79] Work was ahead of schedule, and the planned opening date was on 1 April 1992 moved from May 1993 to 12 December 1992. The last deck section was lifted in place on 4 April 1992. The first tube of the Damsgård Tunnel opened on 10 December, while the second was scheduled for 1 May 1993. West-bound traffic along National Road 555 was in the meantime routes via Laksevåg. Only one tube of the Lyderhorn Tunnel was open, but it instead had one lane in each direction.[80]

Opening and use

The bridge was officially opened on 12 December 1992.[81] At 14:25 the last car ferry ran across the fjord.[82] When the bridge opened, it had the thirteenth-largest suspension bridge span in the world and the longest span in Norway and the Nordic Countries.[83] The toll company proposed charging NOK 100 per passing, the same as the fees on the ferry including advanced tolls. They also proposed reducing the number of price categories from eleven to four. This was rejected by the municipal council, who wanted to keep the number of categories and reduce the toll to NOK 87.[84] The wish of the local politicians was overturned by the Public Roads Administration, who agreed to the terms proposed by the toll company. The tolls were therefore set to NOK 100 for cars up to 6 meters (20 ft) long, NOK 250 for vehicles up to 12.4 meters (41 ft) and NOK 500 for longer vehicles. Tolls were collected only one way, as the bridge is the only road connection to Askøy.[85]

In 2003, the Public Road Administration took initiative for the Askøy Bridge to use the Autopass electronic toll collection system. The national standard was planned implemented simultaneously in the Bergen Toll Ring, the Askøy Bridge and the Osterøy Bridge. This eliminated the need for a manned booth and allowed cars to pass without stopping. The cost-saving would allow the toll collection period to end one month early.[86] Autopass would allow for an annual saving of NOK 6 million.[87] The proposal resulted in opposition from a group of locals, who collected 9,000 signatures in a petition to keep the manual collection system. The old system allowed people to purchase discounted tickets for NOK 60. While people who signed an agreement with Askøybrua AS were granted the same discount, this would not be true for people who had an agreement with other toll companies, and did not sign an additional agreement to receive the discount.[88] The petitioners were concerned that they no longer could purchase tickets for friends visiting them from the mainland, as these would only receive the discount if they signed an agreement with Askøybrua.[89] On 22 December, the toll company voted to introduce a dual system which would both allow Autopass and the old tickets, although it would be a more costly system to operate.[87] On 23 January 2004, the Public Roads Administration announced that they would allow all cars with an Autopass chip to receive the 30 percent discount, even if they had an agreement with a different toll company. Autopass was introduced on 2 February.[90]

In its first year of use, the bridge saw an average daily traffic of 5,000 vehicles.[91] By 2006, this had increased to 10,000. The toll on the bridge stimulated a higher public transport share; while there was in 2006 a 20 percent public transport use in the Bergen Region, transport from Askøy to the mainland had a 35 percent share.[92] The bridge was paid off and the toll plaza removed on 18 November 2006. NOK 1.2 billion had been collected in tolls through 23 years.[93] In 2007, the bridge had an average 14,634 vehicles per day.[2]

Future

The bridge was built wide enough that the pedestrian path can be converted to a car lane, allowing for a three lanes.[1] In the municipal transport plan published in 2007, it was stated that had the bridge been planned then, it would have received four lanes.[94] There have also been proposals for a second bridge to be built next to the existing bridge which would allow for a four-lane motorway.[95] Another proposals is to build the Cross Link, which would consist of two projects, a subsea road tunnel from just south of Herdla in northern Askøy eastwards to Meland, and a ferry connection from northern Askøy westwards to Øygarden. The project is planned to reduce transport times within Nordhordland, and from there to Askøy and Øygarden. It would also relieve some traffic from Bergen City Center.[96] The Hardanger Bridge is scheduled for completion in 2013 and will then overtake the Askøy Bridge as the longest-spanned bridge in Norway.[97]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Askøybroen. |

- Bibliography

- Fossen, Anders Bjarne (1995). Askøybroen: fra drøm til virkelighet (in Norwegian). Askøybrua. ISBN 82-7128-221-2.

- Notes

- "Askøy Bridge" (PDF). Aas-Jakobsen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "ÅDT Nivå 1-punkt Hordaland" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. p. 71. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Fossen (1995): 154

- Fossen (1995): 155

- Fossen (1995): 17

- Fossen (1995): 18

- Fossen (1995): 19

- Fossen (1995): 20

- Fossen (1995): 21

- Fossen (1995): 22

- Fossen (1995): 24

- Fossen (1995): 27

- Fossen (1995): 31

- Fossen (1995): 29

- Fossen (1995): 30

- Fossen (1995): 34

- Fossen (1995): 35

- Fossen (1995): 37

- Fossen (1995): 38

- Fossen (1995): 39

- Fossen (1995): 41

- Fossen (1995): 43

- Fossen (1995): 40

- Fossen (1995): 42

- Fossen (1995): 148

- Fossen (1995): 149

- Fossen (1995): 44

- Fossen (1995): 46

- Fossen (1995): 47

- Fossen (1995): 48

- Fossen (1995): 49

- Fossen (1995): 53

- Fossen (1995): 54

- Fossen (1995): 100

- Fossen (1995): 101

- Fossen (1995): 102

- Fossen (1995): 57

- Fossen (1995): 58

- Fossen (1995): 59

- Fossen (1995): 60

- Fossen (1995): 66

- Fossen (1995): 67

- Fossen (1995): 69

- Fossen (1995): 74

- Fossen (1995): 75

- Fossen (1995): 77

- Fossen (1995): 78

- Fossen (1995): 79

- Fossen (1995): 80

- Fossen (1995): 82

- Fossen (1995): 84

- Fossen (1995): 85

- Fossen (1995): 86

- Fossen (1995): 87

- Fossen (1995): 89

- Fossen (1995): 90

- Fossen (1995): 92

- Fossen (1995): 93

- Fossen (1995): 94

- Fossen (1995): 95

- Fossen (1995): 96

- Fossen (1995): 104

- Fossen (1995): 105

- Fossen (1995): 106

- Fossen (1995): 107

- Fossen (1995): 108

- Fossen (1995): 109

- Fossen (1995): 112

- Fossen (1995): 117

- Fossen (1995): 120

- Fossen (1995): 121

- Fossen (1995): 122

- "Bruene i Salhus og Askøy vedtatt" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 9 December 1987.

- Fossen (1995): 128

- Fossen (1995): 124

- Fossen (1995): 114

- Fossen (1995): 129

- Fossen (1995): 131

- Fossen (1995): 133

- Fossen (1995): 134

- Fossen (1995): 136

- Fossen (1995): 138

- Fossen (1995): 123

- Aarre, Einar (22 April 1992). "87 kroner over Askøybroen". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- Egeland, Åsmund (25 July 1992). "100 kroner for å kjøre over Askøybrua". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- Pedersen, Kari (13 November 2003). "Askøybroen inn i bomsystemet". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Kjetland, Turid (23 December 2003). "Vant kampen mot Autopass". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Sengesæter, Pål (15 June 2004). "Askøybrua raskere nedbetalt". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Nygard-Sture, Trond (15 December 2003). "Samlet 9000 underskrifter mot bomsystem". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Mæland, Pål Andreas (23 January 2004). "Billigare å køyre over Askøybrua". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Fossen (1995): 143

- "Trafikken på broen tredobles". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). 7 November 2006. p. 16.

- "Gratis bro er verd å feire". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). 19 November 2006. p. 14.

- "Samferdselsutredning for Askøy" (in Norwegian). Askøy Municipality. June 2007. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Mæland, Pål Andreas (16 March 2007). "Vil ha fire felt på Askøybrua". Askøyværingen (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Lura, Christian (10 February 2010). "Nå vil Bergen ha tverrsamband". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Lura, Christian (16 June 2010). "Fakta om rv. 7 Hardangerbrua" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.