Armadillo World Headquarters

Armadillo World Headquarters (sometimes referred to as simply The 'Dillo) was a music venue and nightclub in Austin, Texas, from 1970 to 1980.[1][2][3] It was located at 505 Barton Springs Road in Austin. After its demolition, it was replaced by a 13-story office building.

History

In 1970, Austin's flagship rock music venue, the Vulcan Gas Company, closed, leaving the city's nascent and burgeoning live music scene without an incubator. One night, Eddie Wilson, manager of the local group Shiva's Headband, stepped outside a nightclub where the band was playing and noticed an old, abandoned National Guard armory.[4] Wilson found an unlocked garage door on the building and was able to view the cavernous interior using the headlights of his automobile. He had a desire to continue the legacy of the Vulcan Gas Company, and was inspired by what he saw in the armory to create a new music hall in the derelict structure. The armory was estimated to have been built in 1948, but no records of its construction could be or have been located. The building was ugly, uncomfortable, and had poor acoustics, but offered cheap rent and a central location. Posters for the venue usually noted the address as 525½ Barton Springs Road (Rear), behind the Skating Palace (approximate coordinates 30.258 −97.750).

The name for the Armadillo was inspired by the use of armadillos as a symbol in the artwork of Jim Franklin, a local poster artist, and from the building itself. In choosing the mascot for the new venture, Wilson and his partners wanted an "armored" animal since the building was an old armory. The nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) was chosen because of its hard shell that looks like armor, its history as a survivor (virtually unchanged for almost 50 million years), and its near-ubiquity in Central Texas. Wilson also believed the building looked like it had been some type of headquarters at one time. He initially proposed "International Headquarters" but in the end it became "World Headquarters."

In founding the Armadillo World Headquarters[5], Wilson was assisted by Jim Franklin, Mike Tolleson, an entertainment attorney, Bobby Hedderman from the Vulcan Gas Company and Hank Alrich. Funding for the venture was initially provided by Shiva's Headband founder's father, Dan Perskin, and Mad Dog, Inc. an Austin literati group that included Bud Shrake.

The Armadillo World Headquarters officially opened on August 7, 1970 with Shiva's Headband, the Hub City Movers, and Whistler performing.[6] The hall held about 1,500 patrons, but chairs were limited, so most patrons sat on the floor on sections of carpet that had been pieced together.[4]

The Armadillo caught on quickly with the hippie culture of Austin because admission was inexpensive and the hall tolerated cannabis use. Even though illicit drug use was flagrant, the Armadillo was never raided. Anecdotes suggest the police were worried about having to bust their fellow officers as well as local and state politicians.

Soon, the Armadillo started receiving publicity in national magazines such as Rolling Stone. In a story from its September 9, 1974 edition, Time magazine wrote that the Armadillo was to the Austin music scene what The Fillmore had been to the emergence of rock music in the 1960s. The clientele became a mixture of hippies, cowboys, and businessmen who stopped by to have lunch and a beer and listen to live music. At its peak, the amount of Lone Star draft beer sold by the Armadillo was second only to the Houston Astrodome. The Neiman Marcus department store even offered a line of Armadillo-branded products.

The unique blend of country and rock music performed at the hall became known by the terms "The Austin Sound," "Redneck Rock," progressive country or "Cosmic Cowboy." Artists that almost single-handedly defined this particular genre and sound were Michael Martin Murphey, Jerry Jeff Walker and The Lost Gonzo Band.[7][8] Many upcoming and established acts such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Ray Charles, Stevie Ray Vaughan and ZZ Top played the Armadillo. Freddy Fender, Freddie King, Frank Zappa, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, The Sir Douglas Quintet all recorded live albums there. Bruce Springsteen played five shows during 1974. The Australian band AC/DC played their first American show at the Armadillo with Canadian band Moxy in July 1977. The Clash played live at The Armadillo with Joe Ely on October 4, 1979 (a photo from that show appears on the band's London Calling album) and the notorious Austin punk band The Skunks.[9]

Despite its successes, the Armadillo always struggled financially. The addition of the Armadillo Beer Garden in 1972 and the subsequent establishment of food service were both bids to generate steady cash flow.[6] However, the financial difficulties continued. In an interview for the 2010 book Weird City, Eddie Wilson remarked:

"People don’t remember this part: the months and months of drudgery. People talk about the Armadillo like it was a huge success, but there were months where hardly anyone showed up. After the first night when no one really came I ended up crying myself to sleep up on stage."

This predicament was blamed on a combination of large guaranteed payments for the acts, cheap ticket prices, and poor promotion. The club finally had to lay off staff members in late 1976 and file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1977. Another factor in the club's demise was that it sat on 5.62 acres (22,700 m2) of land in what soon became a prime development area in the rapidly growing city. The Armadillo's landlord sold the property for an amount estimated between $4 million and $8 million.

The final concert at the Armadillo took place on December 31, 1980. The sold-out New Year's Eve show featured Asleep at the Wheel and Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen. Some reports say the show ended at 4 am, while others claim that the bands played until dawn. The contents of the Armadillo were sold at auction in January 1981, and the old armory was razed for a high-rise office building.

Legacy

With the success of the Armadillo and Austin's burgeoning music scene, KLRN (now KLRU), the local PBS television affiliate, created Austin City Limits, a program showcasing popular local, regional, and national music acts.

The Armadillo Christmas Bazaar began in 1976 at the Armadillo, and is still held annually during the Christmas season. The Bazaar was another attempt to improve cash flow for the hall. When the Armadillo closed, the Bazaar first moved to Cherry Creek Plaza (1981–1983), and then on to the Austin Opry House (1984–1994). In 1995, the Bazaar settled at the Austin Music Hall for twelve years. Due to remodeling of the Austin Music Hall, the Bazaar had to move its 2007 show to the Austin Convention Center and is currently at the Palmer Events Center. The Bazaar has become one of the top-ranked arts and crafts shows in the nation with a long waiting list of artisans who wish to show their work.

On August 19, 2006, the City of Austin dedicated a commemorative plaque at the site where the Armadillo once stood. Co-founder Eddie Wilson was on hand and stated:

"It is still on the lips and minds of a lot of people 26 years after it closed. This is noteworthy for me because of the zero-tolerance mentality, and now the city erected a memorial that glorifies the things of the past that are not accepted today."

Some acts that played at the Armadillo

- AC/DC[10]

- Jay Boy Adams

- Mose Allison

- Joan Armatrading

- Asleep at the Wheel

- Austin Ballet Theatre[4]

- The B-52's[10]

- Balcones Fault

- Long John Baldry

- Count Basie[4]

- Dickey Betts

- Elvin Bishop

- Blue Öyster Cult

- Tommy Bolin

- The Boomtown Rats

- Brewer & Shipley

- David Bromberg

- Bubble Puppy

- Roy Buchanan

- Budgie

- Jimmy Buffett[4]

- Captain Beefheart

- Joe King Carrasco y El Molino, 1976

- Ray Charles[4]

- Charlie Daniels Band

- Cheech and Chong[10]

- The Clash

- Jimmy Cliff

- David Allan Coe

- Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen[4]

- Ry Cooder

- Alice Cooper

- Elvis Costello

- James Cotton

- Country Joe McDonald

- Jack DeJohnette Special Edition

- Denim

- Rick Derringer

- Devo

- Dire Straits

- The Dixie Dregs

- The Electromagnets

- Joe Ely[9]

- John Fahey

- Fats Domino[4]

- José Feliciano

- Michael Franks

- Gentle Giant

- Dexter Gordon

- Journey

- Jon Emery

- John Klemmer

- Ramblin' Jack Elliott

- Roky Erickson

- The Fabulous Thunderbirds

- Steven Fromholz

- The J. Geils Band

- The Pretenders

- Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys

- Sonny Fortune

- Flying Burrito Brothers

- Freddy Fender

- Gasoline

- Genesis

- Golden Earring

- Greezy Wheels

- Arlo Guthrie

- Mahavishnu Orchestra

- Emmylou Harris

- John Hartford

- It's a Beautiful Day

- Jerry Garcia Band

- Jerry Garcia and Merl Saunders[10]

- Levon Helm

- Bugs Henderson

- Dan Hicks & the Hot Licks

- Hub City Movers[6]

- Lynyrd Skynyrd[10]

- The Jam

- Janis Joplin

- Waylon Jennings[8]

- Freddie King[11]

- Leo Kottke

- Kraftwerk

- Peter Lang

- Jerry Lee Lewis

- Mance Lipscomb

- Little Feat

- Kenny Loggins

- The Lost Gonzo Band

- Mahogany Rush

- Chuck Mangione

- Man Mountain and the Green Slime Boys

- The Marshall Tucker Band

- Moon Martin

- Dave Mason

- Delbert McClinton

- Roger McGuinn

- Pat Metheny

- Augie Meyers

- Bette Midler[4]

- Charles Mingus

- Van Morrison

- Moxy

- Maria Muldaur

- Martin Mull

- Michael Martin Murphey[7]

- Willie Nelson[11]

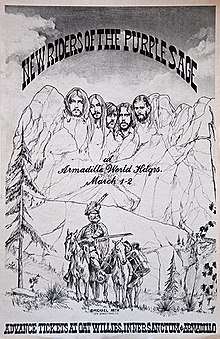

- New Riders of the Purple Sage[12]

- The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

- Ted Nugent

- Phil Ochs

- Old and New Dreams

- Robert Palmer

- Paul Ray and the Cobras

- Roxy Music

- Turk Pipkin

- The Pointer Sisters[10]

- The Police[10]

- Jean-Luc Ponty

- Iggy Pop

- John Prine

- Flora Purim

- The Ramones

- Leon Redbone

- Renaissance

- Rockpile

- Sonny Rollins

- Linda Ronstadt

- The Runaways

- Todd Rundgren

- Rush

- Leon Russell

- Doug Sahm

- San Francisco Mime Troupe[4]

- Savoy Brown

- Boz Scaggs

- Earl Scruggs[6]

- Bob Seger

- Ravi Shankar[6]

- Shiva's Headband[6]

- The Sir Douglas Quintet

- The Skunks

- Patti Smith

- Jimmie Spheeris

- Spirit

- Bruce Springsteen[4]

- St. Elmo's Fire (band)

- B.W. Stevenson

- Skyhooks

- Steeleye Span

- Steely Dan

- Spyro Gyra

- Squeeze

- Taj Mahal

- The Take

- Talking Heads

- Chip Taylor

- Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee

- Thin Lizzy

- George Thorogood

- Kenneth Threadgill

- Too Smooth

- Toots & the Maytals

- Pat Travers

- TT Troll

- Uranium Savages

- Van Halen[10]

- Stevie Ray Vaughan[10]

- Loudon Wainwright III

- Jerry Jeff Walker[7]

- Doc and Merle Watson

- Weather Report

- Bob Weir

- Rusty Wier

- Johnny Winter

- The Paul Winter Consort

- The Wommack Bros. Band

- Phil Woods

- XTC

- Frank Zappa[4]

- ZZ Top

Live recordings made at the Armadillo

- Sleazy Roadside Stories – Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen (Recorded in 1973, released in 1988)

- Live from Deep in the Heart of Texas – Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen (1974)

- Bongo Fury – Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, The Mothers (1975)

- Armadillo World Headquarters, Austin, TX, 6/13/75 – New Riders of the Purple Sage (1975)

- Re-Union of the Cosmic Brothers – Sir Douglas Quintet, Freddy Fender, Roky Erickson (1975)

- Waylon:Live – Waylon Jennings (1976)[8]

- Larger Than Life – Freddie King (some tracks, not full record)[11]

- Live Love – Sir Douglas Quintet (1977)

- Wanted: Dead or Alive - Doug Sahm, Augie Meyers, & Friends (1977)

- Live – Phil Woods 1978

- More Live – Phil Woods (1979)

- At Last – Recorded Live on Stage – The Bugs Henderson Group (1978)

- Live & Deadly Live album – The Cobras (Recorded in 1979 and released in 2011)

See also

- Music of Austin

References

- David Richards (né David Read Richards; born 1933), Once Upon a Time in Texas: A Liberal in the Lone Star State. University of Texas Press (2002), Chapter 21: "The Times They Are A Changin'"; OCLC 884576165Note: Richards, the author, distinguished his career in Texas as a civil rights lawyer; from 1953 to 1984, he was the husband of Ann Richards; a year before they divorced, Ann Richards was elected Texas State Treasurer, which won her the distinction of becoming the first woman (since Ma Ferguson) in 50 years to be elected to a state-wide office; subsequent to their divorce, she went on to become the Texas GovernorLimited search via HathiTrust

- "Virtual Tour: Tribute To Two Austin Music Icons" ("The Armadillo Years: A Visual History"), Henry Gonzalez (né Enrique Barrientos Gonzalez; 1950–2016), SouthPop (South Austin Popular Cultural Center, aka South Austin Museum of Popular Culture) (retrieved May 2017, via southpop

.org ... Anna Gonzalez (née Anna Margarita Gonzalez; born 1983, married to visual artist James Richard Everton) — website registrant; video was uploaded to YouTube March 11, 2011)/tag /henry-gonzalez / - "The Armadillo's Last Waltz," by Richard Erwin Zelade (born 1953), Texas Times, Vol. 6, Winter 1985, pps. 46–49; OCLC 9104814The Texas Times is a bygone tabloid, monthly except June, printed by the Texas Student Publications, Inc. (UT Austin), under the auspices of the University of Texas System; it launched September 1968

- McComb, David G. (September 1, 2008). Spare Time in Texas: Recreation and History in the Lone Star State (First ed.). University of Texas Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0292718896.

- Wilson, Eddie (2017). Armadillo World Headquarters. 6416 North Lamar Blvd., Austin, Texas 78752: TSSI Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4773-1382-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Shank, Berry (April 15, 1994). Dissonant Identities: The Rock’n’Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (First ed.). Wesleyan. pp. 53–56.

- Hillis, Craig D. (2002). "Cowboys and Indians: The International Stage" (PDF). Journal of Texas Music History. 2 (1). Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- Stimeling, Travis D. (2008). "Viva Terlingua: Jerry Jeff Walker, Live Recordings, and the Authenticity of Progressive Country Music" (PDF). Journal of Texas Music History. 8 (1). Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- Joe Ely & The Clash – Live Shots recollections Archived August 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Long, Joshua (May 1, 2010). Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas (First ed.). University of Texas Press. p. 29. ISBN 0292722419.

- Reid, Jan (March 1, 2004). The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock: New Edition. University of Texas Press. p. 7. ISBN 0292701977.

- Horowitz, Hal. "Austin Texas 1975". AllMusic. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armadillo World Headquarters. |

- awhq.com – Armadillo World Headquarters Official Site (website registrant is Threadgill's Restaurant – officially known as Threadgill's Restaurants, Inc. – which, since the mid-1970s, has been owned by Edwin Osbourne Wilson, co-founder of Armadillo World Headquarters)

- AWHQ Website (archive) (website bears the name of the late artist, Bill Narum (1947–2009), former president of the South Austin Popular Culture Center)

- "Armadillo World Headquarters" (www

.austinlinks is owned by Social Craft Media, LLC, of Austin – Mary Y. Greening, President).com - Armadillo Christmas Bazaar (website is registered to Bruce M. Willenzik (born 1947), who, back in the day, worked at Armadillo World Headquarters)

- Armadillo Photo Archive (website registrant is Steve Hopson, né Steven Bradley Hopson, an Austin-based photographer)

- "A Guide to the Armadillo World Headquarters Records, 1971–1980" (materials held by Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin)