Kuressaare

Kuressaare (Estonian pronunciation: [ˈkureˈsˑɑːre]) is a town on Saaremaa island in Estonia. It is the administrative centre of Saaremaa Parish and the capital of Saare County. Kuressaare is the westernmost town in Estonia. The recorded population on 1 January 2018 was 13,276.[1]

Kuressaare | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Kuressaare | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

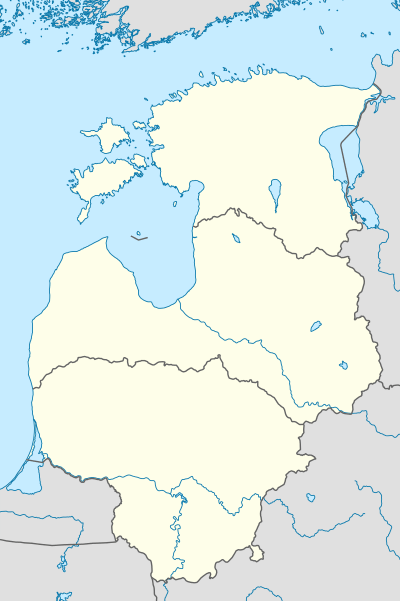

.png) Kuressaare Location of Kuressaare in Estonia  Kuressaare Location of Kuressaare in the Baltic states | |

| Coordinates: 58°15′N 22°29′E | |

| Country | |

| County | |

| First appeared on map | 1154 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Madis Kallas |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.95 km2 (5.77 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 13,276 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 890/km2 (2,300/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Estonians | 97.6% |

| • Russians | 1.2% |

| • Finns | 0.3% |

| • other | 0.9% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 93813 |

| Area code(s) | (+372) 045 |

| Vehicle registration | K |

| Website | www.saaremaavald.ee/en/web/en/local-government |

The town is situated on the southern coast of Saaremaa island, facing the Gulf of Riga of the Baltic Sea, and is served by the Kuressaare Airport, Roomassaare harbour, and Kuressaare yacht harbour.

Names

Kuressaare's historic name Arensburg[2] (from Middle High German a(a)r: eagle, raptor) renders the Latin denotation arx aquilae for the city's castle. The fortress and the eagle, tetramorph symbol of Saint John the Evangelist, are also depicted on Kuressaare's coat of arms.

The town, which grew around the fortress, was simultaneously known as Arensburg and Kuressaarelinn; the latter name being a combination of Kuressaare—an ancient name of the Saaremaa Island—and linn, which means town.[3] Eventually, the town's name shortened to Kuressaare[3] and became official in 1918 after Estonia had declared its independence from Bolshevist Russia. Under the Soviet rule, the town was renamed Kingissepa in 1952; after the Bolshevik Kuressaare-native Viktor Kingissepp[3] executed in 1922. The name Kuressaare was restored in 1990.[3]

History

![]()

![]()

Saare County 1236–1241

![]()

Saare County 1261–1262

![]()

Saare County 1343–1345

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The town first appeared on maps around 1154. The island of Saaremaa (German, Swedish: Ösel) was conquered by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword under Volkwin of Naumburg in 1227, who merged with the Teutonic Knights shortly afterwards.[4] The first documentation of the castle (arx aquilae) was found in Latin texts written in 1381 and 1422. Over time, a town, which became known as Arensburg or Kuressaarelinn,[3] grew and flourished around the fortress. It became the see of the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek established by Albert of Riga in 1228, part of the Terra Mariana.[5]

Johann von Münchhausen, bishop since 1542, converted to Protestantism. With the advance of the troops of Tsar Ivan IV of Russia in the course of the Livonian War, Münchhausen sold his lands to King Frederick II of Denmark in 1559 and returned to Germany. Frederick sent his younger brother Prince Magnus to Kuressaare where he was elected bishop the following year. It was through his influence that the city obtained its civic charter in 1563, modeled after that of Riga.[2] The bishopric was finally secularised in 1572 and Kuressaare fell to the Danish Crown.

In 1645, it passed to Swedish control through the Treaty of Brömsebro after the Danish defeat in the Torstenson War.[2] Queen Christina of Sweden granted her favourite, Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, the title of Count of Arensburg, the German and Swedish name for Kuressaare at that time. The city was burnt to the ground by Russian troops in 1710 during the Great Northern War and suffered heavily from the plague.[6] Abandoned by the Swedes it was incorporated into the Governorate of Livonia of the Russian Empire through the Treaty of Nystad in 1721.

During the 19th century Kuressaare became a popular seaside resort on the Baltic coast. During World War I, between September and October 1917, German land and naval forces occupied Saaremaa with Operation Albion. During World War II, the Battle of Tehumardi took place. In October 1990, Kuressaare was the first town in Estonia to regain its self-governing status.

Neighborhoods of Kuressaare

There are nine neighborhoods of Kuressaare:

- Ida-Niidu

- Kesklinn

- Kellamäe

- Marientali

- Põllu alev

- Roomassaare

- Smuuli

- Suuremõisa

- Tori.[7]

Landmarks and culture

The medieval episcopal Kuressaare Castle today houses the Saaremaa Regional Museum. The original wooden castle was constructed between 1338 and 1380, although other sources claim a fortress was built in Kuressaare as early as 1260.[8][9] In 1968, architect Kalvi Aluve began studies on Kuressaare Castle.[10]

The town hall was originally built in 1654, and restored, retaining classicist and baroque features.[6] It was last restored in the 1960s with dolomite stairs at the front.[6] St Nicolaus Church was built in 1790.[6]

The annual Saaremaa Opera Days (Saaremaa Ooperipäevad) have been held in Kuressaare each summer since 1999. Other festivals include Kuressaare Chamber Music Days (Kuressaare Kammermuusika Päevad), held since 1995 and Kuressaare Maritime Festival (Kuressaare Merepäevad), held since 1998.

Kuressaare also hosts the FC Kuressaare football club.

Climate

| Climate data for Kuressaare (1971–1999) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

1.6 (34.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.9 (23.2) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.6 (−24.9) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−9 (16) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−32.6 (−26.7) |

−32.6 (−26.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.7) |

31 (1.2) |

33 (1.3) |

35 (1.4) |

32 (1.3) |

49 (1.9) |

58 (2.3) |

63 (2.5) |

71 (2.8) |

72 (2.8) |

72 (2.8) |

59 (2.3) |

617 (24.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 118 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 86 | 85 | 79 | 71 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 87 | 82 |

| Source: Estonian Weather Service[11][12] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Transportation

Kuressaare is served by Kuressaare Airport, located on a peninsula southeast of the town. There is regular traffic to Tallinn, as well as seasonal flights to the island of Ruhnu.

There are bus connections around the island, as well as with Kuivastu on Muhu Island, a ferry terminal with connection to the mainland.

In 1917, during the German occupation, an urban railway was built in Kuressaare, and in 1918, it was transferred to the town administration. It connected the port with the city center/ One of the station was provisionally located in Kurhouse, and in 1924, the dedicated Park Station was built. The railway functioned until the 1930s when it was gradually disused and mostly dismantled. An attempt to revive the railway in the beginning of the 1950s, during the Soviet period, was unsuccessful, and ended up with rails fully removed from the streets.[13]

Notable people

- Adam Georg von Agthe (1777–1826), Russian military officer

- Tiiu Aro (born 1952), Estonian physician and politician

- Eugen Dücker (1841–1916), Baltic German painter

- Maria Faust (born 1979), Estonian saxophone player and composer

- Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven (1914–2007), German military officer

- Louis Kahn (1901–1974), American architect

- Madis Kallas (born 1981), Estonian decathlete and politician

- Viktor Kingissepp (1888–1922), Estonian communist politician

- Heli Lääts (1932–2018), Estonian singer

- Karl Patrick Lauk (born 1997), Estonian cyclist

- Tullio Liblik (born 1964), Estonian entrepreneur

- Jörgen Liik (born 1990), Estonian actor

- Ivo Linna (born 1949), Estonian singer

- Richard Maack (1825–1886), Russian naturalist

- Konstantin Märska (1896–1951), Estonian cinematographer and film director

- Gerd Neggo (1891–1974), Estonian dancer and choreographer

- Marek Niit (born 1987), Estonian sprinter

- Sulev Nõmmik (1931–1992), Estonian actor, director, humorist and dancer

- Tiidrek Nurme (born 1985), Estonian runner

- Margus Oopkaup (born 1959), Estonian actor

- Mikk Pahapill (born 1983), Estonian decathlete

- Grete Paia (born 1995), Estonian singer and songwriter

- Tõnis Palts (born 1953), Estonian politician and businessman

- Jüri Pihl (1954–2019), Estonian police officer and politician

- Keith Pupart (born 1985), Estonian volleyball player

- Ilmar Raag (born 1968), Estonian film director and media personality

- Mihkel Räim (born 1993), Estonian cyclist

- Tuuli Rand (born 1990), Estonian singer

- Getter Saar (born 1992), Estonian badminton player

- Indrek Saar (born 1973), Estonian actor and politician

- Benno Schotz (1891–1984), Scottish sculptor

- Hannibal Sehested (1609–1666), Dano-Norwegian statesman

- Karen Sehested (1606–1672), Danish court official

- Adeele Sepp (born 1989), Estonian actor

- Jaanus Tamkivi (born 1959), Estonian politician

- Tarmo Teder (born 1958), Estonian writer and critic

- Ivar Karl Ugi (1930–2005), German chemist

- Voldemar Väli (1903–1997), Estonian wrestler

- Mihail Velsvebel (1926–2008), Estonian runner

- Alexander Vostokov (1781–1864), Russian philologist

- Richard Otto Zöpffel (1843–1891), Baltic German theologian

Twin towns and sister cities

Kuressaare is twinned with:[14]

.svg.png)

Gallery

Kuressaare St. Lawrence Church

Kuressaare St. Lawrence Church- Kuressaare Resort Hall

Residential building

Residential building- Monument to the Estonian War of Independence

Pub in Kuressaare weighthouse

Pub in Kuressaare weighthouse- Big Bridge of Kuressaare

Mill tavern

Mill tavern Town theater

Town theater- Castle Park

Fitness center

Fitness center 8th Street

8th Street Tallinna street, 10

Tallinna street, 10 Buildings in Kuressaare center

Buildings in Kuressaare center Hotel by Kuressaare Castle

Hotel by Kuressaare Castle Kuressaare historical center

Kuressaare historical center Lasteaia street

Lasteaia street

Significant depictions in popular culture

- Arensburg (Kuressaare) is one of the starting towns of the State of the Teutonic Order in the turn-based strategy game Medieval II: Total War: Kingdoms.[15]

References

Notes

- Statistics Estonia

- Bes, Lennart; Frankot, Edda; Brand, Hanno (2007). Baltic Connections: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany. BRILL. p. 178. ISBN 978-90-04-16431-4. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Pospelov, p. 28

- Kjaergaard, Thorkild (1994). Castles around the Baltic Sea: the illustrated guide. Castle Museum. p. 64. ISBN 978-83-86206-03-2. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Murray, Alan V. (2001). Crusade and conversion on the Baltic frontier, 1150–1500. Ashgate. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7546-0325-2. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Taylor, Neil (17 August 2010). Bradt Estonia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-84162-320-7. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "LINNAOSADE JA -JAGUDE LÜHENDID". www.eki.ee (in Estonian). Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture And Customs of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Jarvis, Howard; Ochser, Tim (2 May 2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania. Dorling Kindersley. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4053-6063-0. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Lang, V.; Laneman, Margot (2006). Archaeological research in Estonia, 1865–2005. Tartu University Press. p. 185. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- "Kliimanormid-Õhutemperatuur" (in Estonian). Estonian Weather Service. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Kliimanormid-Sademed, õhuniiskus" (in Estonian). Estonian Weather Service. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Fish, Endel. "Railroad of Saaremaa". Tourism in Saaremaa.

- "Kuressaare sõpruslinnad". Kuressaare linn. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- "The Teutonic Order (M2TW-K-TC faction)". wiki.totalwar.com. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

Sources

- Е. М. Поспелов (Ye. M. Pospelov). "Имена городов: вчера и сегодня (1917–1992). Топонимический словарь." (City Names: Yesterday and Today (1917–1992). Toponymic Dictionary.) Москва, "Русские словари", 1993.

External links

![]()

![]()