Antoon Sallaert

Antoon Sallaert or Anthonis Sallaert[1] (1594–1650)[2] was a Flemish Baroque painter, draughtsman and printmaker who was active in Brussels. Sallaert produced many devotional paintings for the Brussels court of Archdukes Albert and Isabella as well as for the local churches. Sallaert was an innovative printmaker and is credited with the invention of the monotype technique. He was an important tapestry designer for the local weaving workshops.[3]

_-_Crucifixion_of_St_Peter.jpg)

Life

Antoon Sallaert was a pupil of the Brussels painter Michel de Bordeaux starting from 1606.[4] He was registered as a master in the Brussels Guild of Saint Luke in 1613.[5] Some sources mention that Sallaert was a pupil of Peter Paul Rubens or worked in the workshop of Rubens. There does not appear to be evidence for this, although some of his works are close in style to Rubens.[4]

In the 1620s and 1630s Sallaert received commissions from the Archdukes Albert and Isabella but he was never listed as an official court painter. Sallaert was the deacon of the Brussels Guild of Saint Luke in 1633 and in 1648. He received irregular commissions from local nobles and produced religious compositions for the Jesuit churches in and around Brussels. He provided designs for tapestries to the local tapstry workshops. In 1647 he accepted a large commission from the clergy of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk of Alsemberg to paint a series of 11 compositions on the history of the church. The last recorded payment he received for the commission dates to 1649.[4]

He was buried in the Chapel Church Brussels in 1650.[4]

Sallaert married Anna Verbruggen. Their son Jan Baptist Sallaert (baptized on 14 February 1612) trained with his father and became a painter.[6]

Work

General

Sallaert was a versatile artist who worked in various genres and media. He painted religious as well a mythological subjects and was also a portrait painter. He was a regular contributor of designs for local publications and produced many monotypes. He further designed cartoons for the local weaving workshops.[3] Sallaert was known in his time as an accomplished draughtsman and it is possible that his paintings and drawings have been attributed to other artists such as Rubens or Jacob Jordaens.[4]

He used the monograms ASall f and AS entwined.[5]

Paintings

Sallaert's painting style is characterized by its nervous brushstrokes, lively outlines and expressive distortion of the composition and figures. He often used foreshortening as a dramatic effect. His early compositions dating to before 1635 have a strong monumentality and plasticity through light effects. while there usually is a group of figures. These early works followed the style of Rubens' works of c. 1610–20, although it may have been the work of Gaspar de Crayer who resided in Brussels from whom he learned the style.[3] He created ambitious figure compositions and portraits in the Rubens manner.[7] His later works became more dramatic and his style had an almost calligraphic and mannered quality.[3]

Sallaert was in the first place a very accomplished draftsman, particularly in the technique of ink on paper.[4] Like Rubens, he was a master of the oil sketch.[8] Despite a certain dependence on Rubens, his oil sketches have a very personal approach and style. The use of a reddish-brown background tone was characteristic of his oil sketches.[9]

Sallaert painted multiple portraits which were compared to those of Antony van Dyck.[4]

Prints

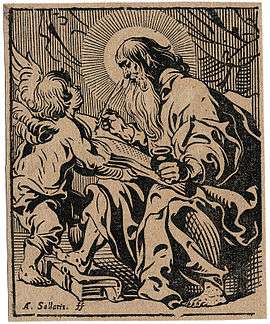

It is primarily in his prints and print designs that Antoon Sallaert proved himself to be one of the most original artists on the Flemish art scene during the Rubens era.[7] He only made a few etchings. About 12 woodcuts are ascribed to Sallaert, some of which are book illustrations. He created about 11 monotypes.[4] In his prints, especially the woodcuts and monotypes, have a clear experimental character. As Sallaert's etchings and woodcuts are very rare, the editions were likely rather small. An example of his woodcuts is The Evangelist Matthew Writing the Gospel which shows his nimble yet forceful linework. Through the contrast between bright, untreated surfaces and dense patches of black Sallaert creates dramatic light effects. A few lines and dark splashes of colour are sufficient in this woodcut for Sallaert to give a strong character to the faces, bodies and garments. The work has an unconventional, even modern outlook. Sallaert's formal language sometimes borders on the caricature and his use of a rare, tinted paper accentuates the experimental character of his woodcuts.[7]

There is still no certainty as to who was the inventor of the monotype process. The Italian artist Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609–64) is often credited as being the first artist to produce monotypes. He made brushed sketches intended as finished and final works of art.[10] He began to make monotypes in the mid 1640s, normally working from black to white, and produced over twenty surviving ones, over half of which are set at night. It is believed that Sallaert created his first monotypes in the early 1640s and is therefore to be regarded as the inventor of this printing process. Both artists used the new technique in different ways. Castiglione created most of his monotypes as black-field images by wiping away ink on a prepared plate thus producing white and grey lines. Sallaert, on the other hand, brushed bold, tapering lines onto the printing surface with meticulous precision. It is likely that Sallaert's monotype style was influenced by the chiaroscuro woodcuts of the Dutch engraver Hendrik Goltzius. Sallaert found in the monotype a technique which was the closest to drawing and oil sketching. His monotypes and drawings are characterised by swelling lines and tapering ends. He often added by hand white highlights to his monotypes. There is a clear economy of line in his drawings and monotypes when compared to his woodcuts and etchings.[4][11] Sallaert clearly appreciated in the monotype technique the freedom to design on a plate before printing it on paper.[8]

Sallaert played an important role as provider of designs and prints to the publishers in Antwerp and Brussels. His print designs outnumbered the number of prints made by himself. The Antwerp engravers Cornelis Galle the Elder and Christoffel Jegher engraved the frontispieces and woodcut book illustrations designed by Sallaert. This attests to Sallaert's close links with artistic circles in Antwerp.[4] Examples of publications on which he worked were the "Perpetua Crux sive Passio Jesu Christi", written by the Jesuit Jodocus Andries. The book was first published in 1649 in Antwerp by Cornelis Woons and frequently re-published between 1649 and 1721. The 40 illustrations were cut by Christoffel Jegher after designs by Sallaert.[12]

Tapestry designs

Antoon Sallaert was a prominent designer of tapestries. Some of the tapestry series he worked on were The sufferings of Cupid, The life of Man and the Sapientia or the Powers that rule the World, which had a moralising intent. The cartoons for the Cupid series can be dated approximately between 1628 and 1639.[13] The series of seven tapestries of the Life of Man were a reflection on the ages of man and were inspired by Otto van Veen's 1607 Emblemata Horatiana.[14] King Philip II of Spain acquired in 1636 a set of tapestries of the Life of Man and the Life of Theseus after designs by Sallaert.[15]

In 1646 Sallaert was granted tax relief by the Brussels city government in recognition of his contribution to the tapestry industry. Sallaert had stressed in his application for tax relief the fact that his introduction of a new style in Brussels tapestry design made it unnecessary for the local workshops to hire non-local artists. This clearly showed a protectionist reflex to Jordaens' involvement in the Brussels tapestry industry. In 1645, only a few months before Sallaert filed his tax relief application, the Brussels tapestry maker Boudewijn van Beveren had hung a cartoon of Jordaens' Proverbs in the church of St Catherine. This had likely bruised Sallaert's ego. Sallaert's tapestry designs included adaptations of 16th-century cartoons. Like other contemporary tapestry designers, Sallaert developed a mixture of traditional 16th-century and new 17th-century styles thus blending one-dimensional monumentality and three-dimensional depth.[16]

References

- First name also: Anthoni and Antoine

- Sallaert's year of birth is usually given as between 1580 and 1590, but as early as 1968 it was demonstrated that Sallaert was baptised in 1594; R. d'Anethan: 'Les Salaert dits de Doncker', Brabantica 9 (1968), p. 254

- Hans Vlieghe. "Sallaert, Anthonis." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 10 March 2016

- Todd D. Weyman, Two Early Monotypes by Sallaert, in: Print Quarterly Vol. 12, No. 2 (JUNE 1995), p. 164-169

- Antoine Sallaert at The Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Jan Baptist Sallaert at Vondel Humanities

- Antoon Sallaert, The Evangelist Matthew Writing the Gospel at Nicolaas Teeuwisse

- Kelley Notaro, An Exhibition of the Finest Monotypes from the Cleveland Museum of Art's Collection at The Cleveland Museum of Art site

- Antoine Sallaert (1594–1650), The four fathers of the church with St Lambert at Sotheby's

- Prints and Printmaking, Antony Griffiths, British Museum Press (in UK), 2nd ed., 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- M. Royalton Kisch, A Monotype by Sallaert, in: Print Quarterly, 1988, V, n. 1, p. 60-61

- Perpetua Crux sive Passio Jesu Christi, Plate 1. Jesus Christ kneeling and holding a cross at the British Museum

- Brosens 2009, p. 363

- Guy Delmarcel, 'Flemish Tapestry from the 15th to the 18th Century', Lannoo Uitgeverij, 1 Jan 1999, p. 240

- Thomas P. Campbell, Pascal-François Bertrand, Jeri Bapasola, 'Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor', Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 January 2007

- Brosens 2009, p. 366

Sources

- Koenraad Brosens and Veerle de Laet, 'Matthijs Roelandts, Joris Leemans and Lanceloot Lefebure: new data on Baroque tapestry in Brussels' in: The Burlington Magazine, vol. CLI, June 2009

External links