Antimicrobial surface

An antimicrobial surface contains an antimicrobial agent that inhibits the ability of microorganisms to grow[1] on the surface of a material. Such surfaces are becoming more widely investigated for possible use in various settings including clinics, industry, and even the home. The most common and most important use of antimicrobial coatings has been in the healthcare setting for sterilization of medical devices to prevent hospital associated infections, which have accounted for almost 100,000 deaths in the United States.[2] In addition to medical devices, linens and clothing can provide a suitable environment for many bacteria, fungi, and viruses to grow when in contact with the human body which allows for the transmission of infectious disease.[3]

Antimicrobial surfaces are functionalized in a variety of different processes. A coating may be applied to a surface that has a chemical compound which is toxic to microorganism. Other surfaces may be functionalized by attaching a polymer, or polypeptide to its surface.[2]

An innovation in antimicrobial surfaces is the discovery that copper and its alloys (brasses, bronzes, cupronickel, copper-nickel-zinc, and others) are natural antimicrobial materials that have intrinsic properties to destroy a wide range of microorganisms.[4][5] An abundance of peer-reviewed antimicrobial efficacy studies have been published regarding copper’s efficacy to destroy E. coli O157:H7, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile, influenza A virus, adenovirus, and fungi.[6] For further information regarding efficacy studies, clinical studies (including U.S. Department of Defense clinical trials), United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registrations with public health claims for 355 Antimicrobial Copper (Cu+) alloys, and a list of EPA-registered antimicrobial copper products, see: Antimicrobial copper touch surfaces and Antimicrobial properties of copper.

Apart from the health industry, antimicrobial surfaces have been utilized for their ability to keep surfaces cleaned. Either the physical nature of the surface, or the chemical make up can be manipulated to create an environment which cannot be inhabited by microorganisms for a variety of different reasons. Photocatalytic materials have been used for their ability to kill many microorganisms and therefore can be used for self-cleaning surfaces as well as air cleaning, water purification, and antitumor activity.[7]

Antimicrobial activity

Mechanisms

Silver

Silver ions have been shown to react with the thiol group in enzymes and inactivate them, leading to cell death.[8] These ions can inhibit oxidative enzymes such as yeast alcohol dehydrogenase.[9] Silver ions have also been shown to interact with DNA to enhance pyrimidine dimerization by the photodynamic reaction and possibly prevent DNA replication.[10]

The use of silver as an antimicrobial is well documented.

Copper

The antimicrobial mechanisms of copper have been studied for decades and are still under investigation. A summary of potential mechanisms is available here: Antimicrobial properties of copper#Mechanisms of antibacterial action of copper.[11] Researchers today believe that the most important mechanisms include the following:

- Elevated copper levels inside a cell causes oxidative stress and the generation of hydrogen peroxide. Under these conditions, copper participates in the so-called Fenton-type reaction — a chemical reaction causing oxidative damage to cells.

- Excess copper causes a decline in the membrane integrity of microbes, leading to leakage of specific essential cell nutrients, such as potassium and glutamate. This leads to desiccation and subsequent cell death.

- While copper is needed for many protein functions, in an excess situation (as on a copper alloy surface), copper binds to proteins that do not require copper for their function. This "inappropriate" binding leads to loss-of-function of the protein, and/or breakdown of the protein into nonfunctional portions.

Organosilanes

Organosilane coatings do not yield lower mean ACCs than those observed in controls.[12]

Nutrient Uptake

The growth rate of E. coli and S. aureus was found to be independent of nutrient concentrations on non-antimicrobial surfaces.[13] It was also noted that antimicrobial agents such as Novaron AG 300 (Silver sodium hydrogen zirconium phosphate) do not inhibit the growth rate of E. coli or S. aureus when nutrient concentrations are high, but do as they are decreased. This result leads to the possible antimicrobial mechanism of limiting the cell's uptake, or use efficiency, of nutrients.[13]

Quaternary ammonium

The quaternary ammonium compound Dimethyloctadecyl (3-trimethoxysilyl propyl) ammonium chloride (Si-QAC) has been found to have antimicrobial activity when covalently bonded to a surface.[14] Many other quaternary ammonium compounds are known to have antimicrobial properties (e.g. alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride and didecyldimethylammonium chloride). These last two are membrane active compounds; against S. aureus the first forms a single monolayer coverage of the S. aureus cells on the outer membrane, while the second forms a double monolayer.[15] This leads to cell leakage and total release of the intracellular potassium and 260 nm-absorbing pools in this order.[15]

Selectivity

By definition, "antimicrobial" refers to something that is detrimental to a microbe. Because the definition of a microbe (or microorganism) is very general, something that is "antimicrobial" could have a detrimental effect against a range of organisms ranging from beneficial to harmful ones, and could include mammalian cells and cell types typically associated with disease such as bacteria, viruses, protozoans, and fungi.

Selectivity refers to the ability to combat a certain type or class of organism. Depending on the application, the ability to selectively combat certain microorganisms while having little detrimental effect against others dictates the usefulness of a particular antimicrobial surface in a given context.

Bactericides

A main way to combat the growth of bacterial cells on a surface is to prevent the initial adhesion of the cells to that surface. Some coatings which accomplish this include chlorhexidine incorporated hydroxyapatite coatings, chlorhexidine-containing polylactide coatings on an anodized surface, and polymer and calcium phosphate coatings with chlorhexidine.[16]

Antibiotic coatings provide another way of preventing the growth of bacteria. Gentamicin is an antibiotic which has a relatively broad antibacterial spectrum. Also, gentamincin is one of the rare kinds of thermo stable antibiotics and so it is one of the most widely used antibiotics for coating titanium implants.[16] Other antibiotics with broad antibacterial spectra are cephalothin, carbenicillin, amoxicillin, cefamandol, tobramycin, and vancomycin.[16]

Copper and copper alloy surfaces are an effective means for preventing the growth of bacteria. Extensive U.S. EPA-supervised antimicrobial efficacy tests on Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Escherichia coli 0157:H7, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have determined that when cleaned regularly, some 355 different EPA-registrered antimicrobial copper alloy surfaces:

- Continuously reduce bacterial contamination, achieving 99.9% reduction within two hours of exposure;

- Kill greater than 99.9% of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria within two hours of exposure;

- Deliver continuous and ongoing antibacterial action, remaining effective in killing greater than 99.9% of bacteria within two hours;

- Kill greater than 99.9% of bacteria within two hours, and continue to kill 99% of bacteria even after repeated contamination;

- Help inhibit the buildup and growth of bacteria within two hours of exposure between routing cleaning and sanitizing steps.

See: Antimicrobial copper touch surfaces for main article.

Viral inhibitors

Influenza viruses are mainly spread from person to person through airborne droplets produced while coughing or sneezing. However, the viruses can also be transmitted when a person touches respiratory droplets settled on an object or surface.[17] It is during this stage that an antiviral surface could play the biggest role in cutting down on the spread of a virus. Glass slides painted with the hydrophobic long-chained polycation N,N dodecyl,methyl-polyethylenimine (N,N-dodecyl,methyl-PEI) are highly lethal to waterborne influenza A viruses, including not only wild-type human and avian strains but also their neuraminidase mutants resistant to anti-influenza drugs.[18]

Copper alloy surfaces have been investigated for their antiviral efficacies.[19] After incubation for one hour on copper, active influenza A virus particles were reduced by 75%. After six hours, the particles were reduced on copper by 99.999%.[20][21] Also, 75% of Adenovirus particles were inactivated on copper (C11000) within 1 hour. Within six hours, 99.999% of the adenovirus particles were inactivated.[22]

Fungal inhibitors

A chromogranin A-derived antifungal peptide (CGA 47-66, chromofungin) when embedded on a surface has been shown to have antifungal activity by interacting with the fungal membrane and thereby penetrating into the cell.[23] Additionally, in vitro studies have demonstrated that such an antifungal coating is able to inhibit the growth of yeast Candida albicans by 65% and completely stop the proliferation of filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa.[23]

Copper and copper alloy surfaces have demonstrated a die-off of Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Penicillium chrysogenum, Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans fungal spores.[24] Hence, the potential to help prevent the spread of fungi that cause human infections by using copper alloys (instead of non-antifungal metals) in air conditioning systems is worthy of further investigation.

Surface modification

Physical modification

Surface roughness

The physical topology of a surface will determine the viable environment for bacteria. It may affect the ability for a microbe to adhere to its surface. Textile surfaces, tend to be very easy for microbes to adhere due to the abundance of interstitial spacing between fibers.

Wenzel Model was developed to calculate the dependence that surface roughness has on the observed contact angle. Surfaces that are not atomically smooth will exhibit an observed contact angle that varies from the actual contact angle of the surface. The equation is expressed as:

where R is the ratio of the actual area of the surface to the observed area of a surface and θ is the Young's contact angle as defined for an ideal surface.[25] See Wetting.

Chemical modification

Grafting polymers onto and/or from surfaces

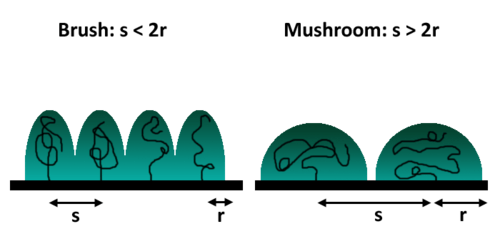

Antimicrobial activity can be imparted onto a surface through the grafting of functionalized polymers, for example those terminated with quaternary amine functional groups, through one of two principle methods. With these methods—“grafting to” and “grafting from”—polymers can be chemically bound to a solid surface and thus the properties of the surface (i.e. antimicrobial activity) can be controlled.[25] Quaternary ammonium ion-containing polymers (PQA) have been proven to effectively kill cells and spores through their interactions with cell membranes.[26] A wealth of nitrogenous monomers can be quaternized to be biologically active. These monomers, for example 2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) or 4-vinyl pyridine (4-VP) can be subsequently polymerized with ATRP.[26] Thus antimicrobial surfaces can be prepared via “grafting to” or “grafting from” mechanisms.

Grafting onto

Grafting to involves the strong adsorption or chemical bonding of a polymer molecule to a surface from solution. This process is typically achieved through a coupling agent that links a handle on the surface to a reactive group on either of the chain termini. Although simple, this approach suffers from the disadvantage of a relatively low grafting density as a result of steric hindrance from the already-attached polymer coils. After coupling, as in all cases, polymers attempt to maximize their entropy typically by assuming a brush or mushroom conformation. Thus, potential binding sites become inaccessible beneath this “mushroom domain”.[25]

Pre-synthesized polymers, like the PDMEAMA/PTMSPMA block copolymer, can be immobilized on a surface (i.e. glass) by simply immersing the surface in an aqueous solution containing the polymer.[26] For a process like this, grafting density depends on the concentration and molecular weight of the polymer as well as the amount time the surface was immersed in solution.[26] As expected, an inverse relationship exists between grafting density and molecular weight.[26] As the antimicrobial activity depends on the concentration of quaternary ammonium tethered to the surface, grafting density and molecular weight represent opposing factors that can be manipulated to achieve high efficacy.

Grafting from

This limitation can be overcome by polymerizing directly on the surface. This process is referred to as grafting from, or surface-initiated polymerization (SIP). As the name suggests, the initiator molecules must be immobilized on the solid surface. Like other polymerization methods, SIP can be tailored to follow radical, anionic, or cationic mechanisms and can be controlled utilizing reversible addition transfer polymerization (RAFT), atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), or nitroxide-mediated techniques.[25]

A controlled polymerization allows for the formation of stretched conformation polymer structures that maximize grafting density and thus biocidal efficiency.[26] This process also allows for high density grafting of high molecular weight polymer which further improves efficacy.[26]

Superhydrophobic surfaces

A superhydrophobic surface is a low energy, generally rough surface on which water has a contact angle of >150°. Nonpolar materials such as hydrocarbons traditionally have relatively low surface energies, however this property alone is not sufficient to achieve superhydrophobicity. Superhydrophobic surfaces can be created in a number of ways, however most of the synthesis strategies are inspired by natural designs. The Cassie-Baxter model provides an explanation for superhydropbicity—air trapped in microgrooves of a rough surface create a “composite” surface consisting of air and the tops of microprotrusions.[27] This structure is maintained as the scale of the features decreases, thus many approaches to the synthesis of superhydrophobic surfaces have focused on the fractal contribution.[27] Wax solidification, lithography, vapor deposition, template methods, polymer reconfirmation, sublimation, plasma, electrospinning, sol-gel processing, electrochemical methods, hydrothermal synthesis, layer-by-layer deposition, and one-pot reactions are approaches to the creation of superhydrophobic surfaces that have been suggested.[27]

Making a surface superhydrophobic represents an efficient means of imparting antimicrobial activity. A passive antibacterial effect results from the poor ability of microbes to adhere to the surface. The area of superhydropboic textiles takes advantage of this and could have potential applications as antimicrobial coatings.

Fluorocarbons

Fluorocarbons and especially perfluorocarbons are excellent substrate materials for the creation of superhydropbobic surfaces due to their extremely low surface energy. These types of materials are synthesized via the replacement of hydrogen atoms with fluorine atoms of a hydrocarbon.

Nanomaterials

Nanoparticles are used for a variety of different antimicrobial applications due to their extraordinary behavior. There are more studies being carried out on the ability for nanomaterials to be utilized for antimicrobial coatings due to their highly reactive nature.[3]

| Nanomaterial | Characteristic | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium dioxide | photo catalytic activity, low cost | UV protection, anti-bacterial, environmental purification, self-cleaning, solar cell efficiency |

| Organosilane | prevent adhesion by abrasive surface, low cost | antimicrobial coating with long-term effectiveness |

| Silver | electrical Conductivity, low toxicity | anti-microbial activity - bind and destroy cell membrane |

| Zinc oxide | photo catalytic activity | anti-microbial activity, used in textile industry |

| Copper | electrical conductivity | UV protection properties, anti-microbial additive |

| Magnetite | superparamagnetic | antimicrobial activity, generate radicals that cause protein damage |

| Magnesium oxide | high specific surface area | antimicrobial activity, generate oxygen radicals that cause protein damage |

| Gold | electrical conductivity | anti-bacterial, acne curing agent |

| Gallium | similar to Fe3+ (essential metabolic nutrient for bacteria) | anti-bacterial against Clostridium difficile |

| Carbon nanotubes | antistatic, electrical conductivity, absorption | CNT/TiO2 nanocomposits; antimicrobial surfaces, fire retardant, anti-static.[3] |

There are quite a few physical characteristics that promote anti-microbial activity. However, most metal ions have the ability to create oxygen radicals, thus forming molecular oxygen which is highly toxic to bacteria.[3]

Coatings

Self-cleaning coatings

Photocatalytic coatings are those that include components (additives) that catalyze reactions, generally through a free radical mechanism, when excited by light. The photocatalytic activity (PCA) of a material provides a measure of its reactive potential, based on the ability of the material to create an electron hole pair when exposed to ultra-violet light.[28] Free radicals formed can oxidize and therefore breakdown organic materials, such as latex binders found in waterborne coatings. Antimicrobial coatings systems take advantage of this by including photocatalytically active compounds in their formulations (i.e. titanium dioxide) that cause the coating to “flake” off over time.[28] These flakes carry the microbes along with them, leaving a “clean” coating behind. Systems like this are often described to be self-cleaning.

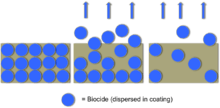

Antimicrobial additives

Instead of doping a surface directly, antimicrobial activity can be imparted to a surface by applying a coating containing antimicrobial agents such as biocides or silver nanoparticles. In the case of the latter, the nanoparticles can have beneficial effects on the structural properties of the coating along with their antibacterial effect.[29]

Antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) have gained a lot of attention because they are much less susceptible to development of microbial resistance.[2] Other antibiotics may be susceptible to bacterial resistance, like multi-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which is known as a common relic in the healthcare industry while other bacterial strains have become more of a concern for waste water treatment in local rivers or bays.[30] AMPs can be functionalized onto a surface by either chemical or physical attachment. AMPs can be physically attached by using oppositely charged polymeric layers and sandwiching the polypeptide between them. This may be repeated to achieve multiple layers of AMPs for the recurring antibacterial activity.[30] There are, however, a few drawbacks to this mechanism. Assembly thickness and polymer-peptide interactions can affect the diffusion of peptide to bacterial contact.[30] Further research should be carried out to determine the effectiveness of the adsorption technique. However, the chemical attachment of AMPs is also widely studied.

AMPs can be covalently bound to a surface, which minimizes the "leaching effect" of peptides. The peptide is typically attached by a very exergonic chemical reaction, thus forming a very stable antimicrobial surface. The surface can be functionalized first with a polymer resin such as polyethylene glycol (PEG).[30] Recent research has focused on producing synthetic polymers and nanomaterials with similar mechanisms of action to endogenous antimicrobial peptides.[31][32]

Touch surfaces

Antimicrobial touch surfaces include all the various kinds of surfaces (such as door knobs, railings, tray tables, etc.) that are often touched by people at work or in everyday life, especially (for example) in hospitals and clinics.

Antimicrobial copper alloy touch surfaces are surfaces that are made from the metal copper or alloys of copper, such as brass and bronze. Copper and copper alloys have a natural ability to kill harmful microbes relatively rapidly - often within two hours or less (i.e. copper alloy surfaces are antimicrobial). Much of the antimicrobial efficacy work pertaining to copper has been or is currently being conducted at the University of Southampton and Northumbria University (United Kingdom), University of Stellenbosch (South Africa), Panjab University (India), University of Chile (Chile), Kitasato University (Japan), the Instituto do Mar[33] and University of Coimbra (Portugal), and the University of Nebraska and Arizona State University (U.S.). Clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of copper alloys to reduce the incidence of nosocomial infections are on-going at hospitals in the UK, Chile, Japan, South Africa, and the U.S.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approved the registrations of 355 different copper alloys as “antimicrobial materials” with public health benefits.[34]

Application

Water Treatment

Antimicrobial Peptides and Chitosan

Naturally occurring chitin and certain peptides have been recognized for their antimicrobial properties in the past. Today, these materials are engineered into nanoparticles in order to produce low-cost disinfection applications. Natural peptides form nano-scale channels in the bacterial cell membranes, which causes osmotic collapse.[35] These peptides are now synthesized in order to tailor the antimicrobial nanostructures with respect to size, morphology, coatings, derivatization, and other properties allowing them to be used for specific antimicrobial properties as desired. Chitosan is a polymer obtained from chitin in arthropod shells, and has been used for its antibacterial properties for a while, but even more so since the polymer has been made into nanoparticles. Chitosan proves to be effective against bacteria, viruses, and fungi, however it is more effective against fungi and viruses than bacteria. The positively charged chitosan nanoparticles interact with the negatively charged cell membrane, which causes an increase in membrane permeability and eventually the intracellular components leak and rupture.[35]

Silver Nanoparticles

Silver compounds and silver ions also have been known to show antimicrobial properties and have been used in a wide range of applications, including water treatment. It is shown that silver ions prevent DNA replication and affect the structure and permeability of the cell membrane. Silver also leads to UV inactivation of bacteria and viruses because silver ions are photoactive in the presence of UV-A and UV-C irradiation. Cysteine and silver ions form a complex that leads to the inactivation of Haemophilus influenzae phage and bacteriophage MS2.[35]

Limitations

We need to understand that almost all bacteria have evolved genes to control their physiology and thereby allow them to resist toxic metal ions (such as Ag(I), Cd(II), Ni(II), etc.). There are also other mechanisms that have been developed such as enzymatic transformations (oxidation, reduction, methylation and de-methylation) and metal-binding proteins (e.g. metallothionein). Furthermore the evolution of persister phenotypes is possible, which means that the bacteria slow their growth or even stop dividing in the presence of toxic materials. Therefore water purification is not a simple matter of adding toxic metal ions to your water. We need to understand much more about the core microbial evolution principles before we continue research into nanomaterial-antimicrobial methods.[36]

Medical and commercial applications

Surgical devices

Even with all the precautions taken by medical professionals, infection reportedly occurs in up to 13.9% of patients after stabilization of an open fracture, and in about 0.5-2% of patients who receive joint prostheses.[37] In order to reduce these numbers, the surfaces of the devices used in these procedures have been altered in hopes to prevent the growth of the bacteria that leads to these infections. This has been achieved by coating titanium devices with an antiseptic combination of chlorhexidine and chloroxylenol. This antiseptic combination successfully prevents the growth of the five main organisms that cause medical related infections, which include Staphylococcus epidermidis, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans.[37]

Photocatalytic coatings

Photoactive pigments such as TiO2 and ZnO have been used on glass, ceramic, and steel substrates for self-cleaning and antimicrobial purposes. For photocatalytic bactericidal activity in water treatment applications, granular substrate materials have been used in the form of sands supporting mixed anatase/rutile TiO2 coatings.[38] Oxide semiconductor photocatalysts such as TiO2 react with incident irradiation exceeding the material's electronic band-gap resulting in the formation of electron-hole pairs (excitons) and the secondary generation of radical species through reaction with adsorbates at the photocatalyst surface yielding an oxidative or reductive effect that degrades living organisms.[39][40] Titania has successfully be used as an antimicrobial coating on bathroom tiles, paving slabs, deodorizers, self-cleaning windows, and many more.

Copper touch surfaces

Copper alloy surfaces have intrinsic properties to destroy a wide range of microorganisms.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which oversees the regulation of antimicrobial agents and materials in that country, found that copper alloys kill more than 99.9% of disease-causing bacteria within just two hours when cleaned regularly.[34] Copper and copper alloys are unique classes of solid materials as no other solid touch surfaces have permission in the U.S. to make human health claims (EPA public health registrations were previously restricted only to liquid and gaseous products). The EPA has granted antimicrobial registration status to 355 different copper alloy compositions.[34] In healthcare applications, EPA-approved antimicrobial copper products include bedrails, handrails, over-bed tables, sinks, faucets, door knobs, toilet hardware, intravenous poles, computer keyboards, etc. In public facility applications, EPA-approved antimicrobial copper products include health club equipment, elevator equipment, shopping cart handles, etc. In residential building applications, EPA-approved antimicrobial copper products include kitchen surfaces, bedrails, footboards, door push plates, towel bars, toilet hardware, wall tiles, etc. In mass transit facilities, EPA-approved antimicrobial copper products include handrails, stair rails grab bars, chairs, benches, etc. A comprehensive list of copper alloy surface products that have been granted antimicrobial registration status with public health claims by the EPA can be found here: Antimicrobial copper-alloy touch surfaces#Approved products.

Clinical trials are currently being conducted on microbial strains unique to individual healthcare facilities around the world to evaluate to what extent copper alloys can reduce the incidence of infection in hospital environments. Early results disclosed in 2011 from clinical studies funded by the U.S. Department of Defense that are taking place at intensive care units (ICUs) at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, the Medical University of South Carolina, and the Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center in Charleston, South Carolina indicate that rooms where common touch surfaces were replaced with copper demonstrated a 97% reduction in surface pathogens versus the non-coppered rooms and that patients in the coppered ICU rooms had a 40.4% lower risk of contracting a hospital acquired infection versus patients in non-coppered ICU rooms.[41][42][43]

Anti-fouling coatings

Marine Biofouling is described as the undesirable buildup of microorganisms, plants, and animals on artificial surfaces immersed in water.[44] Significant buildup of biofouling on marine vessels can be problematic. Traditionally, biocides, a chemical substance or microorganism that can control the growth of harmful organisms by chemical or biological means, are used in order to prevent marine biofouling. Biocides can be either synthetic, such as tributyltin (TBT), or natural, which are derived from bacteria or plants.[44] TBT was historically the main biocide used for anti-fouling coatings, but more recently TBT compounds have been considered toxic chemicals which have negative effects on human and environment, and have been banned by the International Maritime Organization.[45] The early design of anti-fouling coatings consisted of the active ingredients (e.g. TBT) dispersed in the coating in which they "leached" into the sea water, killing any microbes or other marine life that had attached to the ship. The release rate for the biocide however tended to be uncontrolled and often rapid, leaving the coating only effective for 18 to 24 months before all the biocide leached out of the coating.[45]

This problem however was resolved with the use of so-called self-polishing paints, in which the biocide was released at a slower rate as the seawater reacted with the surface layer of the paint.[45] More recently, copper-based anti-fouling paints have been used because they are less toxic than TBT in aquatic environment, but are only effective against marine animal life, and not so much weed growth. Non-stick coatings contain no biocide, but have extremely slippery surfaces which prevents most fouling and makes it easier to clean the little fouling that does occur. Natural biocides are found on marine organisms such as coral and sponges and also prevent fouling if applied to a vessel. Creating a difference in electrical charge between the hull and sea water is a common practice in the prevention of fouling. This technology has proven to be effective, but is easily damaged and can be expensive. Finally, microscopic prickles can be added to a coating, and depending on length and distribution have shown the ability to prevent the attachment of most biofouling.[45]

See also

- Antibiotic resistance

- Antimicrobial

- Antimicrobial copper alloy touch surfaces

- Antimicrobial peptides

- Antimicrobial properties of copper

- Fluorocarbon

- Superhydrophobe

References

- "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:antibacterial". Archived from the original on 2010-11-18. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Onaizi, S.A.; Leong, S.S.J. (2011). "Tethering Antimicrobial Peptides". Biotech. Advances. 29 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.08.012. PMID 20817088.

- Dastjerdi, R.; Montazer, M. (2010). "A review on the application of inorganic nano-structured materials in the modification of textiles: Focus on anti-microbial properties". Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 79: 5–18. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.03.029.

- Antimicrobial properties of copper

- Antimicrobial copper touch surfaces

- "Copper Touch Surfaces". Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- Fujishima, A.; Rao, T.; Tryk, D.A. (2000). "Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysis". J. Photochem. And Photobio C. 1: 1–21. doi:10.1016/S1389-5567(00)00002-2.

- Liau, S. Y.; Read, D. C.; Pugh, W. J.; Furr, J. R.; Russell, A. D. (1997). "Interaction of silver nitrate with readily identifiable groups: relationship to the antibacterial action of silver ions". Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 25 (4): 279–283. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00219.x. PMID 9351278.

- Snodgrass, P. J.; Vallee, B. L.; Hoch, F. L. (1960). "Effects of silver and mercurials on yeast alcohol dehydrogenase". J. Biol. Chem. 235: 504–508. PMID 13832302.

- Russell, A. D.; Hugo, W. B. (1994). Antimicrobial activity and action of silver. Prog. Med. Chem. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. 31. pp. 351–370. doi:10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70024-9. ISBN 9780444818072. PMID 8029478.

- Antimicrobial properties of copper#Mechanisms of antibacterial action of copper

- John, Boyce (2014). "Evaluation of two organosilane products for sustained antimicrobial activity on high-touch surfaces in patient rooms". American Journal of Infection Control. 42 (3): 326–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.09.009. PMID 24406256.

- Yamada, H (2010). "Direct Observation and Analysis of Bacterial Growth on an Antimicrobial Surface". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 (16): 5409–5414. doi:10.1128/aem.00576-10. PMC 2918969. PMID 20562272.

- Isquith, A. J.; et al. (1972). "Surface-Bonded Antimicrobial Activity of an Organosilicon Quaternary Ammonium Chloride". Applied Microbiology. 24 (6): 859–863. doi:10.1128/AEM.24.6.859-863.1972.

- Ioannou, C.; Hanlon, G.; Denyer, S. (2007). "Action of Disinfectant Quaternary Ammonium Compounds against Staphylococcus aureus" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 51 (1): 296–306. doi:10.1128/aac.00375-06. PMC 1797692. PMID 17060529.

- Zhao, L.; Chu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhifen, Wu (2009). "Antibacterial Coatings on Titanium Implants". J. Biomed. Mater. 91B (1): 471–480. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31463. PMID 19637369.

- Wright, P. F., Webster, R. G. 2001. Orthomyxoviruses, fields virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. pp 1533–1579

- Haldar, J.; et al. (2008). "Hydrophobic polycationic coatings inactivate wild-type and zanamivir- and/or oseltamivir-resistant human and avian influenza viruses". Biotechnology. 30 (3): 475–479. doi:10.1007/s10529-007-9565-5. PMID 17972018.

- Antimicrobial properties of copper#Antimicrobial efficacy of copper alloy touch surfaces

- Noyce, JO; Michels, H; Keevil, CW (2007). "Inactivation of influenza A virus on copper versus stainless steel surfaces". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 73 (8): 2748–50. doi:10.1128/AEM.01139-06. PMC 1855605. PMID 17259354.

- "Viruses Influenza A". Archived from the original on 2009-10-18. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2011-09-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Etiennea, O.; Gasnier, C.; et al. (2005). "Antifungal coating by biofunctionalized polyelectrolyte multilayered films". Biomaterials. 26 (33): 6704–6712. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.068. PMID 15992921.

- Weaver, L.; Michels, H.T.; Keevil, C.W. (2010). "Potential for preventing spread of fungi in air-conditioning systems constructed using copper instead of aluminium". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 50 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02753.x. PMID 19943884.

- Butt, H., Graf, K., Kappl, M. Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces. 2003. Wiley-VCH.

- http://www.cmu.edu/maty/materials/Properties-of-well-defined/functional-biomaterials.html

- Xue, C., Jia, S., Zhang, J., Ma, J. Large-area fabrication of superhydrophobic surfaces for practical applications: an overview. 2010. Sci. Tech. Adv. Mat. 11: 1-15.

- http://www.titaniumart.com/photocatalysis-ti02.html

- Leyland, Nigel S.; Podporska-Carroll, Joanna; Browne, John; Hinder, Steven J.; Quilty, Brid; Pillai, Suresh C. (2016). "Highly Efficient F, Cu doped TiO2 anti-bacterial visible light active photocatalytic coatings to combat hospital-acquired infections". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 24770. Bibcode:2016NatSR...624770L. doi:10.1038/srep24770. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4838873. PMID 27098010.

- Huang, J., Hu. H., Lu, S., Li, Y., Tang, F., Lu, Y., Wei, B. 2011.Monitoring and evaluation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria at a municipal wastewater treatment plant in China. Environ. Int.

- Floros, Michael C.; Bortolatto, Janaína F.; Oliveira, Osmir B.; Salvador, Sergio L.; Narine, Suresh S. (2016-03-14). "Antimicrobial Activity of Amphiphilic Triazole-Linked Polymers Derived from Renewable Sources". ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2 (3): 336–343. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00412.

- Lam, Shu J.; O'Brien-Simpson, Neil M.; Pantarat, Namfon; Sulistio, Adrian; Wong, Edgar H. H.; Chen, Yu-Yen; Lenzo, Jason C.; Holden, James A.; Blencowe, Anton (2016). "Combating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria with structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers". Nature Microbiology. 1 (11): 16162. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.162. PMID 27617798.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2019-05-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- EPA registers copper-containing alloy products, May 2008

- Li, Q.; Mahendra, S.; Lyon, D.; Brunet, L.; Liga, M.; Li, D.; Alvarez, P. (2008). "Antimicrobial Nanomaterials for Water Disinfection and Microbial Control: Potential Applications and Implications". Water Research. 42 (18): 4591–602. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2008.08.015. PMID 18804836.

- Graves, J.L., Jr.; Thomas, M.; Ewunkem, J.A. Antimicrobial Nanomaterials: Why Evolution Matters. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 283.

- Darouiche, Rabih O.; Green, Gregory; Mansouri, Mohammad D. (1998). "Antimicrobial Activity of Antiseptic-coated Orthopaedic Devices". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 10 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00017-x. PMID 9624548.

- Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Sorrell, Charles C. (2014). "Sand Supported Mixed-Phase TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Decontamination Applications". Advanced Engineering Materials. 16 (2): 248–254. arXiv:1404.2652. Bibcode:2014arXiv1404.2652H. doi:10.1002/adem.201300259.

- Cushnie TP, Robertson PK, Officer S, Pollard PM, Prabhu R, McCullagh C, Robertson JM (2010). "Photobactericidal effects of TiO2 thin films at low temperature". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry. 216 (2–3): 290–294. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2010.06.027.

- Hochmannova, L., and J. Vytrasova. "Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Effects of Interior Paints." Progress in Organic Coatings (2009).

- http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1753-6561-5-s6-o53.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-09-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- World Health Organization’s 1st International Conference on Prevention and Infection Control (ICPIC) in Geneva, Switzerland on July 1st, 2011

- Yebra, Diego M.; Kiil, Soren; Dam-Johansen, Kim (2004). "Antifouling technology - past, present and future steps towards efficient and environmentally friendly antifouling coatings". Progress in Organic Coatings. 50 (2): 75–104. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2003.06.001.

- "Focus on IMO - Anti-fouling systems". International Maritime Organisation.