Anti-nuclear movement in California

The 1970s proved to be a pivotal period for the anti-nuclear movement in California. Opposition to nuclear power in California coincided with the growth of the country's environmental movement. Opposition to nuclear power increased when President Richard Nixon called for the construction of 1000 nuclear plants by the year 2000.[1]

| Anti-nuclear movement |

|---|

|

| By country |

| Lists |

The movement succeeded in blocking plans to build a large number of facilities in the state as well as closing operating power plants. The confrontation between nuclear power advocates and environmentalists grew to include the use of non-violent civil disobedience.[2]

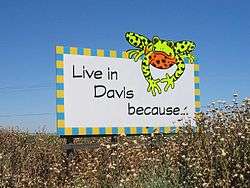

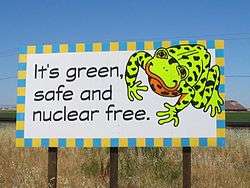

In 1976 the state of California placed a moratorium on new reactors until a solution to radioactive waste disposal was in place, and two years later state politicians canceled the proposed Sundesert Nuclear Power Plant. In September 1981, over 1,900 arrests took place during a ten-day blockade at Diablo Canyon Power Plant. As part of a national anti-nuclear weapons movement Californians passed a 1982 statewide initiative calling for the end of nuclear weapons.[3] In 1984, the Davis City Council declared the city to be a nuclear free zone.

In 2013, San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station Units 2 and 3 were permanently closed, ending nuclear power in Southern California.[4][5] The state's final two operating reactors at Diablo Canyon are scheduled to close no later than 2025.

Early conflicts

The birth of the anti-nuclear movement in California can be traced to controversy over Pacific Gas and Electric Company's attempt to build the nation's first commercially viable nuclear power plant in Bodega Bay. This conflict began in 1958 and ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of these plans. Subsequent plans to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were also abandoned.[6]

1970s and 1980s

- Nuclear power plants in California

As the anti-nuclear movement grew in California, some scientists and engineers began supporting the positions of the activists. They were influenced by the Ecology and Free Speech Movements that had inspired activists and had impacted the public consciousness.[6] Californian's for Nuclear Safeguards would succeed at placing Proposition 15 on the June 1976 ballot which would have banned new facilities and put additional safety requirements on operating reactors.[7] The initiative failed to pass with millions of dollars spent by the nuclear industry to influence the outcome. However, as a result of the publicity which included the resignation of three General Electric nuclear engineers, the state legislature passed a moratorium on further nuclear development until a permanent solution to high level waste was in place.[8][9][10]

The discovery of a fault near General Electric's Vallecitos Nuclear Center near Pleasanton resulted in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission closing the facility down in 1977.

Anti-nuclear groups campaigned to stop construction of several proposed plants in the seventies, especially those located on the coast and near fault lines. These proposals included the San Joaquin Nuclear Project, overwhelmingly rejected by Kern County voters in March 1978 by a 70–30% margin.[11] A few months later, the proposed Sundesert Nuclear Power Plant was refused a permit[12][13] by the California Energy Commission, who, a year before the Three Mile Island accident, refused to allow the San Diego Gas & Electric Company to begin construction of the Sundesert units in the "absence of federally demonstrated and approved technology for permanent disposal of radioactive wastes".[14][15]

Protests over Diablo Canyon

Over a two-week period in 1981, 1,900 activists were arrested at Diablo Canyon Power Plant. It was the largest arrest in the history of the anti-nuclear movement in the United States.[16][17] Specific protests included:

- August 6, 1977: The Abalone Alliance held the first blockade at Diablo Canyon Power Plant, and 47 people were arrested.[18]

- August 1978: almost 500 people were arrested for protesting at Diablo Canyon.[18]

- April 8, 1979: 30,000 people marched in San Francisco to support shutting down the Diablo Canyon Power Plant.[19]

- June 30, 1979: about 40,000 people attended a protest rally at Diablo Canyon.[20]

- September 1981: more than 1900 protesters were arrested at Diablo Canyon.[18][21]

- May 1984: about 130 demonstrators showed up for start-up day at Diablo Canyon, and five were arrested.[22]

During this period there were controversies within the Sierra Club about how to lead the anti-nuclear movement, and this led to a split over the Diablo Canyon plant which ended in success for the utilities. The split led to the formation of Friends of the Earth, led by David Brower.[6]

Rancho Seco and San Onofre

In 1979, Abalone Alliance members held a 38-day sit-in in the Californian Governor Jerry Brown's office to protest continued operation of Rancho Seco Nuclear Generating Station, which was a duplicate of the Three Mile Island facility.[23] In 1989, Sacramento voters voted to shut down the Rancho Seco power plant.[24] The salient issues were mostly economic; the plant kept breaking down, and it had been shut from late 1985 to early 1988 for repairs, forcing the district to buy electricity from neighbors.[25]

On June 22, 1980, about 15,000 people attended a protest near San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station.[26] In 1977 Bechtel Corporation installed the [27] reactor vessel backwards.

California has banned the approval of new nuclear reactors since the late 1970s because of concerns over waste disposal.[28][29]

Media coverage

Dark Circle is a 1982 American documentary film that focuses on the connections between the nuclear weapons and the nuclear power industries, with a strong emphasis on the individual human and protracted U.S. environmental costs involved. A clear point made by the film is that while only two bombs were dropped on Japan, many hundreds were exploded in the United States. The film won the Grand Prize for documentary at the Sundance Film Festival and received a national Emmy Award for "Outstanding individual achievement in news and documentary."[30] The film shows anti-nuclear protest activities directed at the Diablo Canyon Power Plant on the California coast in the USA. The protesters contend, and the movie supports, the assertion that the protests were responsible for delaying the licensing of the Diablo Canyon Power Plant and, as a result of the delay, the uncovering of serious construction errors was made public just before the plant went online and started producing power. For example, earthquake supports for nuclear piping had been installed backwards, and the film includes close up footage of the moment that this information became known.

1990s

On June 15, 1990, the Bureau of Land Management published the draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for the construction of a Low-level Nuclear waste repository to be located at Ward valley California. The company applying to construct and operate the repository was U.S. Ecology. An eight-year struggle between government agencies and opponents of the nuclear waste dump ended with the dump being blocked.[31]

Nuclear-free communities

On November 14, 1984, the Davis City Council declared the city to be a nuclear free zone.[32] Another well-known nuclear-free community is Berkeley, California, whose citizens passed the Nuclear Free Berkeley Act in 1986 which allows the city to levy fines for nuclear weapons-related activity and to boycott companies involved in the United States nuclear infrastructure.

Recent developments

PG&E announced its decision to pursue license renewal for Diablo Canyon in November 2009, and local officials "came out in support because of the economic importance of the plant and its 1,200 employees and $25 million in annual property taxes".[33] However, local anti-nuclear activists oppose renewal and want PG&E to focus more on renewable energy. They are also concerned "about the seismic safety of the plant given the recent discovery of a new earthquake fault nearby".[33]

In April 2011, there was demonstration of 300 people at Avila Beach calling for the closure of Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant and a halt to its relicensing application process. The event, organized by San Luis Obispo-based anti-nuclear group Mothers for Peace, was in response to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan.[34]

In 2013, San Onofre 2 and 3 were permanently closed.[4][5]

In June 2016, Pacific Gas and Electric announced plans to retire the Diablo Canyon Power Plant after its current U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission operating licenses expire in November 2024 and August 2025.[35]

See also

- Anti-nuclear groups in the United States

- Anti-nuclear protests in the United States

- California electricity crisis

- J. Samuel Walker

- List of articles associated with nuclear issues in California

- Nuclear power debate

- Nuclear-free zone

- Politics of New England

- Renewable energy in the United States

- Santa Susana Field Laboratory

- Solar power in California

- Wind power in California

References

- New York Times

- San Diego Gas & Electric, Sundesert Nuclear Power Plant Collection

- 1982 California Proposition 12

- Mark Cooper (18 June 2013). "Nuclear aging: Not so graceful". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- Matthew Wald (June 14, 2013). "Nuclear Plants, Old and Uncompetitive, Are Closing Earlier Than Expected". New York Times.

- Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978

- Time Magazine

- California State Assembly. "An act to add Section 25524.1 to the Public Resources Code, relating to energy resources". 1975–1976 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 194 p. 374.

- California State Assembly. "An act to add Section 25524.3 to the Public Resources Code, relating to energy resources". 1975–1976 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 195 p. 376.

- California State Assembly. "An act to add Section 25524.2 to the Public Resources Code, relating to energy resources". 1975–1976 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 196 p. 378.

25524.2. No nuclear fission thermal powerplant, including any to which the provisions of this chapter do not otherwise apply, but excepting those exempted herein, shall be permitted land use in the state, or where applicable, be certified by the commission until both conditions (a) and (b) have been met:

(a) The commission finds that there has been developed and that the United States through its authorized agency has approved and there exists a demonstrated technology or means for the disposal of high-level nuclear waste.

(b) The commission has reported its findings and the reasons therefor pursuant to paragraph (a) to the Legislature. Such reports of findings shall be assigned to appropriate policy committees for review. - Californian, The Bakersfield. "An unlikely no-nuke zone". Bakersfield.com. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1978/04/14/major-nuclear-power-plant-rejected-in-california/69d4ddeb-5780-4f65-9b8e-f39da3c6bcae/

- August S. Carstens Collection

- Luther J. Carter "Political Fallout from Three Mile Island", Science, 204, April 13, 1979, p. 154.

- Thomas Raymond Wellock (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-299-15854-5.

- Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon

- Daniel Pope. Conservation Fallout (book review), H-Net Reviews, August 2007.

- Marco Giugni (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7425-1827-8.

- Amplifying Public Opinion: The Policy Impact of the U.S. Environmental Movement p. 7.

- Gottlieb, Robert (2005). Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement, Revised Edition, Island Press, USA. ISBN 978-1-59726-761-8. p. 240.

- Arrests Exceed 900 In Coast Nuclear Protest New York Times, September 18, 1981.

- Testing and Protesting Time, May 14, 1984.

- Joan Jeffers McCleary (2004). The Hippie Dictionary: A Cultural Encyclopedia (and Phraseicon) of the 1960s and 1970s. Ten Speed Press. p. 659. ISBN 978-1-58008-547-2.

- Shutting Down Rancho Seco

- Matthew L. Wald. Vermont Senate Votes to Close Nuclear Plant The New York Times, February 24, 2010.

- Williams, Eesha. Wikipedia distorts nuclear history Valley Post, May 1, 2008.

- San Onofre San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station

- Jim Doyle. Nuclear power industry sees opening for revival San Francisco Chronicle, March 9, 2009.

- Minnesota also has a moratorium on construction of nuclear power plants, which has been in place since 1994. See Minnesota House says no to new nuclear power plants Archived May 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine StarTribune.com, April 30, 2009.

- Dark Circle, DVD release date March 27, 2007, Directors: Judy Irving, Chris Beaver, Ruth Landy. ISBN 0-7670-9304-6.

- Ward Valley Timeline

- Nuclear Free Zone

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission dealing with multiple issues at Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant

- Julia Hickey (April 17, 2001). "Anti-nuclear rally at Avila Beach". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22.

- https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-diablo-canyon-nuclear-20160621-snap-story.html

Further reading

- Brown, Jerry and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers.

- Lovins, Amory B. and Price, John H. (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- Natti, Susanna and Acker, Bonnie (1979). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power, South End Press.

- Ondaatje, Elizabeth H. (c1988). Trends in Antinuclear Protests in the United States, 1984–1987, Rand Corporation.

- Price, Jerome (1982). The Antinuclear Movement, Twayne Publishers.

- Smith, Jennifer (Editor), (2002). The Antinuclear Movement, Cengage Gale.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

- Wellock, Thomas R. (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-15850-0

- Wills, John (2006). Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon, University of Nevada Press.