Anterior cruciate ligament

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of a pair of cruciate ligaments (the other being the posterior cruciate ligament) in the human knee. The 2 ligaments are also called cruciform ligaments, as they are arranged in a crossed formation. In the quadruped stifle joint (analogous to the knee), based on its anatomical position, it is also referred to as the cranial cruciate ligament.[1] The term cruciate translates to cross. This name is fitting because the ACL crosses the posterior cruciate ligament to form an “X”. It is composed of strong fibrous material and assists in controlling excessive motion. This is done by limiting mobility of the joint. The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the four main ligaments of the knee, providing 85% of the restraining force to anterior tibial displacement at 30 degrees and 90 degrees of knee flexion.[2] The ACL is the most injured ligament of the four located in the knee.

| Anterior cruciate ligament | |

|---|---|

Diagram of the right knee. Anterior cruciate ligament labeled at center left. | |

| Details | |

| From | lateral condyle of the femur |

| To | intercondyloid eminence of the tibia |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ligamentum cruciatum anterius |

| MeSH | D016118 |

| TA | A03.6.08.007 |

| FMA | 44614 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The ACL originates from deep within the notch of the distal femur. Its proximal fibers fan out along the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle. There are two bundles of the ACL: the anteromedial and the posterolateral, named according to where the bundles insert into the tibial plateau. The tibia plateau is a critical weight-bearing region on the upper extremity of the tibia. The ACL attaches in front of the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia, where it blends with the anterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Purpose

The purpose of the ACL is to resist the motions of anterior tibial translation and internal tibial rotation; this is important in order to have rotational stability.[3] This function prevents anterior tibial subluxation of the lateral and medial tibiofemoral joints, which is important for the pivot-shift phenomena.[3] The ACL has been proven to have mechanoreceptors that detect changes in direction of movement, position of the knee joint, changes in acceleration, speed, and tension.[4] A key factor in instability after ACL injuries is having altered neuromuscular function secondary to diminished somatosensory information.[4] For athletes who participate in sports involving cutting, jumping, and rapid deceleration it is important for the knee to be stable in terminal extension, which is the screw-home mechanism.[4]

Clinical significance

Injury

An ACL tear is one of the most common knee injuries, with over 100,000 tears occurring annually in the US.[5] Most ACL tears are a result of a non-contact mechanism such as a sudden change in a direction causing the knee to rotate inward.[6] As the knee rotates inward additional strain is placed on the ACL, since the femur and tibia, which are the two bones that articulate together forming the knee joint, move in opposite directions causing the ACL to tear. Most athletes will require reconstructive surgery on the ACL, in which the torn or ruptured ACL is completely removed and replaced with a piece of tendon or ligament tissue from the patient (autograft) or from a donor (allograft).[7] Conservative treatment has poor outcomes in ACL injury since the ACL is unable to form a fibrous clot as it receives most of its nutrients from the synovial fluid which washes away the reparative cells making it difficult for new fibrous tissue to form. The two most common sources for tissue are the patellar ligament and the hamstrings tendon.[8] The patellar ligament is often used, since bone plugs on each end of the graft are extracted which helps integrate the graft into the bone tunnels, during reconstruction.[9] The surgery is arthroscopic, meaning that a tiny camera is inserted through a small surgical cut.[7] The camera sends video to a large monitor so that the surgeon can see any damage to the ligaments. In the event of an autograft, the surgeon will make a larger cut to get the needed tissue. In the event of an allograft, in which material is donated, this is not necessary since no tissue is taken directly from the patient's own body.[10] The surgeon will drill a hole forming the tibial bone tunnel and femoral bone tunnel, allowing for the patient's new ACL graft to be guided through.[10] Once the graft is pulled through the bone tunnels, two screws are placed into the tibial and femoral bone tunnel.[10] Recovery time ranges between one and two years or longer, depending if the patient chose an autograft or allograft. A week or so after the occurrence of the injury, the athlete is usually deceived by the fact that he/she is walking normally and not feeling much pain.[10] This is dangerous as some athletes start resuming some of their activities such as jogging which, with a wrong move or twist, could damage the bones as the graft has not completely become integrated into the bone tunnels. It is important for the injured athlete to understand the significance of each step of an ACL injury to avoid complications and ensure a proper recovery.

Non-operative treatment of the ACL

ACL reconstruction is the most common treatment for an ACL tear, however it is not the only treatment available for individuals. Some individuals may find it more beneficial to complete a non-operative rehab program. Both individuals who are going to continue with physical activity that involves cutting and pivoting, and individuals who are no longer participating in those specific activities are candidates for the non-operative route.[11] A study was completed comparing operative and non-operative approaches to ACL tears and there were few differences noted by both surgical and nonsurgical groups. However, there was no significant differences in regard to knee function or muscle strength reported by the patient.[12]

The main goals to achieve during rehabilitation of an ACL tear is to regain sufficient functional stability, maximize full muscle strength, and decrease risk of re-injury.[13] There are typically three phases involved in non-operative treatment. These phases include the Acute Phase, the Neuromuscular Training Phase, and the Return to Sport Phase. During the acute phase, the rehab is focusing on the acute symptoms that occur right after the injury and are causing an impairment. The use of therapeutic exercises and appropriate therapeutic modalities is crucial during this phase to assist in repairing the impairments from the injury. The Neuromuscular Training Phase is used to focus on the patient regaining full strength in both the lower extremity and the core muscles. This phase begins when the patient regains full range of motion, no effusion, and adequate lower extremity strength. During this phase the patient will complete advanced balance, proprioception, cardiovascular conditioning, and neuromuscular interventions.[11] The final phase is the Return to Sport Phase, and during this phase the patient will focus on sport-specific activities and agility. A functional performance brace is suggested to be used during the phase to assist with stability during pivoting and cutting activities.[11]

Operative treatment of the ACL

Anterior cruciate ligament surgery is a complex operation that requires expertise in the field of orthopedic and sports medicine. Many factors should be considered when discussing surgery including the athlete's level of competition, age, previous knee injury, other injuries sustained, leg alignment and graft choice. There are typically four graft types to choose from, the bone-patella tendon-bone graft, the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons (quadrupled hamstring tendon), quadriceps tendon, and an allograft.[14] Although there has been extensive research on which grafts are the best, the surgeon will typically choose the type of graft he or she is most comfortable with. If rehabilitated correctly, the reconstruction should last. In fact studies show that 92.9% of patients are happy with graft choice.[14]

Prehabilitation has become an integral part of the ACL reconstruction process. This means that the patient will be doing exercises before getting surgery to maintain factors like range of motion and strength. Research shows that based on a single leg hop test and self-reported assessment, prehab improved function; these effects sustained 12 weeks postoperatively.[15]

Post-surgical rehabilitation is essential in the recovery from the reconstruction. This will typically take a patient 6 to 12 months to return to life as it was prior to the injury.[16] The rehab will be divided into 5 phases which include; protection of the graft, improving range of motion, decrease swelling, and regaining muscle control.[16] Each phase will have different exercises based on the patients needs. For example, while the ligament is healing the patient should be not be fully weight bearing but should strengthen the quad and hamstrings by doing quad sets and weight shifting drills. Phase 2 would require fully weight-bearing and correcting gait patterns, so exercises like core strengthening and balance exercises would be appropriate. Phase 3, the patient will begin running but can do aquatic workouts to help with reducing joint stresses and cardiorespiratory endurance. Phase 4 includes multiplanar movements, so enhancing running program and beginning agility and plyometric drills. Lastly, is phase 5 which focuses on sport specific, or life specific things depending on the patient.[16]

A 2010 Los Angeles Times review of two medical studies discussed whether ACL reconstruction was advisable. One study found that children under 14 who had ACL reconstruction fared better after early surgery than those who underwent a delayed surgery. But for adults 18 to 35, patients who underwent early surgery followed by rehabilitation fared no better than those who had rehabilitative therapy and a later surgery.[17]

The first report focused on children and the timing of an ACL reconstruction. ACL injuries in children are a challenge because children have open growth plates in the bottom of the femur or thigh bone and on the top of the tibia or shin. An ACL reconstruction will typically cross the growth plates, posing a theoretical risk of injury to the growth plate, stunting leg growth or causing the leg to grow at an unusual angle.[18]

The second study noted in the L.A. Times piece focused on adults. It found no significant statistical difference in performance and pain outcomes for patients who receive early ACL reconstruction vs. those who receive physical therapy with an option for later surgery. This would suggest that many patients without instability, buckling or giving way after a course of rehabilitation can be managed non-operatively. However, the study points to the need for more extensive research, was limited to outcomes after two years and did not involve patients who were serious athletes.[17] Patients involved in sports requiring significant cutting, pivoting, twisting or rapid acceleration or deceleration may not be able to participate in these activities without ACL reconstruction. The randomized control study was originally published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[19]

ACL injuries in women

Risk differences among men and women can be attributed to a combination of multiple factors including anatomical, hormonal, genetic, positional, neuromuscular, and environmental factors.[20] The size of the anterior cruciate ligament is often the most heard of difference. Studies look at the length, cross-sectional area, and volume of ACLs. Researchers use cadavers, and in vivo to study these factors, and most studies confirm that women have smaller anterior cruciate ligaments. Other factors that could contribute to higher risks of ACL tears in women include patient weight and height, the size and depth of the intercondylar notch, the diameter of the ACL, the magnitude of the tibial slope, the volume of the tibial spines, the convexity of the lateral tibiofemoral articular surfaces, and the concavity of the medial tibial plateau.[21] While anatomical factors are most talked about, extrinsic factors, including dynamic movement patterns, might be the most important risk factor when it comes to ACL injury.[22] Environmental factors also play a big role. Extrinsic factors are controlled by the individual. These could be strength, conditioning, shoes, and motivation.

Additional images

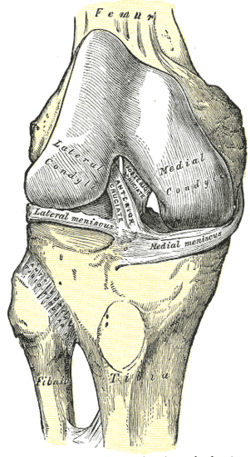

Right knee-joint, from the front, showing interior ligaments.

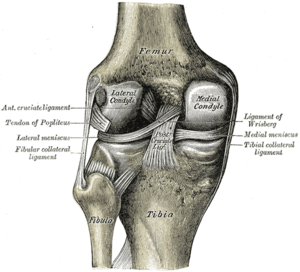

Right knee-joint, from the front, showing interior ligaments. Left knee-joint from behind, showing interior ligaments.

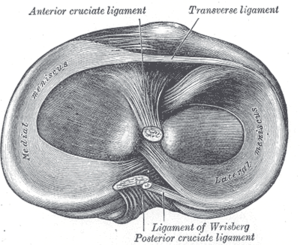

Left knee-joint from behind, showing interior ligaments. Head of right tibia seen from above, showing menisci and attachments of ligaments.

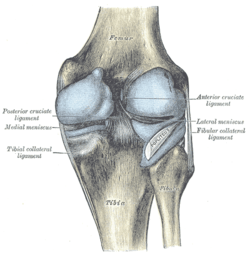

Head of right tibia seen from above, showing menisci and attachments of ligaments. Capsule of right knee-joint (distended). Posterior aspect.

Capsule of right knee-joint (distended). Posterior aspect. MRI shows normal signal of both cruciate ligaments (arrows).

MRI shows normal signal of both cruciate ligaments (arrows).- Knee joint. Deep dissection. Anteromedial view.

See also

References

- "Canine Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease" (PDF). Melbourne Veterinary Referral Centre. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- Ellison, A. E.; Berg, E. E. (1985). "Embryology, anatomy, and function of the anterior cruciate ligament". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 16 (1): 3–14. PMID 3969275.

- Noyes, Frank R. (January 2009). "The Function of the Human Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Analysis of Single- and Double-Bundle Graft Reconstructions". Sports Health. 1 (1): 66–75. doi:10.1177/1941738108326980. ISSN 1941-7381. PMC 3445115. PMID 23015856.

- Liu-Ambrose, T. (December 2003). "The anterior cruciate ligament and functional stability of the knee joint". British Columbia Medical Journal. 45 (10): 495–499. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Cimino, Francesca; Volk, Bradford Scott; Setter, Don (2010-10-15). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention". American Family Physician. 82 (8). ISSN 0002-838X.

- MD, Michael Khadavi, MD and Michael Fredericson. "ACL Injury: Causes and Risk Factors". Sports-health. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- "ACL reconstruction - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Samuelsen, Brian T.; Webster, Kate E.; Johnson, Nick R.; Hewett, Timothy E.; Krych, Aaron J. (October 2017). "Hamstring Autograft versus Patellar Tendon Autograft for ACL Reconstruction: Is There a Difference in Graft Failure Rate? A Meta-analysis of 47,613 Patients". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475 (10): 2459–2468. doi:10.1007/s11999-017-5278-9. ISSN 1528-1132. PMC 5599382. PMID 28205075.

- "When Would You Use Patellar Tendon Autograft as Your Main Graft Selection?". www.healio.com. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- "ACL Injury: Does It Require Surgery? - OrthoInfo - AAOS". Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Paterno, Mark V. (2017-07-29). "Non-operative Care of the Patient with an ACL-Deficient Knee". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 10 (3): 322–327. doi:10.1007/s12178-017-9431-6. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 5577432. PMID 28756525.

- "Options for nonoperative treatment of ACL injuries exist, but remain controversial". Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Physiopedia Contributors (September 25, 2018). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Rehabilitation". Physiopedia.

- Macaulay, Alec A.; Perfetti, Dean C.; Levine, William N. (January 2012). "Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft Choices". Sports Health. 4 (1): 63–68. doi:10.1177/1941738111409890. ISSN 1941-7381. PMC 3435898. PMID 23016071.

- Shaarani, Shahril R.; O'Hare, Christopher; Quinn, Alison; Moyna, Niall; Moran, Raymond; O'Byrne, John M. (September 2013). "Effect of prehabilitation on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 41 (9): 2117–2127. doi:10.1177/0363546513493594. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 23845398.

- "Rehabilitation Guidelines for ACL Reconstruction in the Adult Athlete (Skeletally Mature)" (PDF). UW Health.

- Stein, Jeannine (2010-07-22). "Studies on ACL surgery". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- "ACL Tears: To reconstruct or not, and if so, when?". howardluksmd.com. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- Frobell, Richard B.; Roos, Ewa M.; Roos, Harald P.; Ranstam, Jonas; Lohmander, L. Stefan (2010). "A Randomized Trial of Treatment for Acute Anterior Crut Tears". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (4): 331–342. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. PMID 20660401.

- Chandrashekara, Naveen; Mansourib, Hossein; Slauterbeckc, James; Hashemia, Javad (2006). "Sex-based differences in the tensile properties of the human anterior cruciate ligament". Journal of Biomechanics. 39 (16): 2943–2950. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.031. PMID 16387307.

- Schneider, Antione; Si-Mohamed, Salim; Magnussen, Robert; Lustig, Sebastien; Neyret, Philippe; Servien, Elvire (October 2017). "Tibiofemoral joint congruence is lower in females with ACL injuries than males with ACL injuries". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 25 (5): 1375–1383. doi:10.1007/s00167-017-4756-7. PMID 29052744.

- Lloyd Ireland, Mary (2002). "The female ACL: why is it more prone to injury?". Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 33 (2): 637–651. doi:10.1016/S0030-5898(02)00028-7. PMC 4805849. PMID 12528906.

External links

- Anatomy photo:17:02-0701 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Extremity: Knee joint"

- Anatomy figure: 17:07-08 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Superior view of the tibia."

- Anatomy figure: 17:08-03 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Medial and lateral views of the knee joint and cruciate ligaments."

- lljoints at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (antkneejointopenflexed)