Anopheles walkeri

Anopheles walkeri is a species of mosquito found predominantly throughout the Mississippi River Valley,[1] with its habitat ranging as far north as southern Quebec, Canada.[2] The eggs of A. walkeri are laid directly on the water surface in freshwater swamp habitats.[3] Since its eggs are not resistant to desiccation, this species is restricted to swampy regions with plenty of water. Anopheles walkeri, as with many other anophelines, begins to become active later in the evening than most other mosquito species in its range. This species becomes especially active late at night when in search of a blood meal.[4] Feeding activity is affected greatly by environmental conditions within its microclimate. Wind, low humidity and cool temperatures (around 10 °C or 50 °F and below), are all negatively correlated with feeding aggression.[4]

| Anopheles walkeri | |

|---|---|

| |

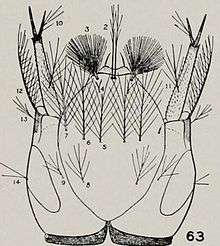

| Head of Anopheles walkeri larva | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. walkeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Anopheles walkeri Theobald, 1901 | |

Life cycle

Anopheles walkeri has a multivoltine life cycle.[3] It produces a hardy winter egg which differs morphologically from the more vulnerable summer eggs by having enlarged floats on the dorsal side.[3] By overwintering in egg form, this species is able to mature through one full larval generation before hibernating adults of other species are able to become active. The multivoltine life cycle means this species is active during both the swampy, open water conditions of early spring, as well as later in the year after the swampland has become thickened with plant growth. It takes about 10 days to mature through the larval stages and pupate, dependent on temperature and water conditions.[5] Adults will typically mate within a few hours of emergence from their pupated form.[6] The females then begin to seek out a blood meal to provide necessary protein to facilitate egg development. The female will then rest while the eggs develop. Once mature, the eggs are oviposited and the female begins the process all over again, feeding and laying for the 40 days or so that it lives for.[6]

Epidemiology

Due to habitat preferences, coupled with particularly low rates of virus detection, Anopheles walkeri is considered to be an unlikely vector of West Nile virus to humans.[7] In addition, it has not been shown to demonstrate any capacity of transmitting avian malaria (Plasmodium circumflexum and P. polare).[8] However, specimens of A. walkeri in the southern United States have been shown to harbor the human infecting strains of malaria, Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum, albeit infrequently (freq= <0.005).[9]

References

- Matheson, R.; Hurlbut, H. S. (1937). "Notes on Anopheles walkeri Theobald". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 17 (2): 237–243. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1937.s1-17.237.

- Ellis, R. A.; Chapman, H. C. (1980). "Mermithid parasites of Canadian anophelines". Mosquito News. 40 (1): 115–116.

- Crans, W. J. (2004). "A classification system for mosquito life cycles: life cycle types for mosquitoes of northeastern United States". Journal of Vector Ecology.

- Grimstad, P. R.; DeFoliart, G. R. (1975). "Mosquito nectar feeding in Wisconsin in relation to twilight and microclimate". Journal of Medical Entomology. 11 (6): 691–698. doi:10.1093/jmedent/11.6.691.

- Shaman, J.; Steiglitz, M.; Stark, C.; Le Blancq S.; Cane, M. (2002). "Using a dynamic hydrology model to predict mosquito abundances in flood and swamp water". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (1): 8–13. doi:10.3201/eid0801.010049. PMC 2730265. PMID 11749741.

- Shaman, J.; Spiegelman, M.; Crane, M.; Stieglitz, M. (2006). "A hydrologically driven model of swamp water mosquito population dynamics". Ecological Modelling. 194 (4): 395–404. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.10.037.

- Andreadis, T. G.; Anderson, J. F.; Vossbrinck, C. R.; Main, A. J. (2004). "Epidemiology of West Nile virus in Connecticut: A five-year analysis of mosquito data 1999-2003". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 4 (4): 360–378. doi:10.1089/vbz.2004.4.360.

- Meyer, C. L.; Bennett, G. F. (1976). "Observations on the sporogony of Plasmodium circumflexum Kikuth and Plasmodium polare Manwell in New Brunswick". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 54 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1139/z76-014. PMID 3278.

- Bang, F. B.; Quimby, G. E.; Simpson, T. W. (1940). "Anopheles walkeri (Theobald) a wild-caught specimen harboring malarial Plasmodia". Public Health Reports. 55 (3): 119–120. doi:10.2307/4583155.