Angim

The work known by its incipit, Angim, "The Return of Ninurta to Nippur", is a rather obsequious 210-line mythological praise poem for the ancient Mesopotamian warrior-god Ninurta, describing his return to Nippur from an expedition to the mountains (KUR), where he boasts of his triumphs against "rebel lands" (KI.BAL), boasting to Enlil in the Ekur, before returning to the Ešumeša temple – to “manifest his authority and kingship.”

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

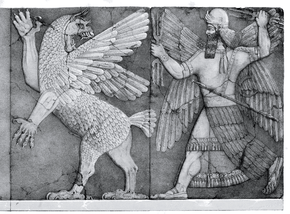

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

The ancient Sumerian epic had been provided with an intralinear Akkadian translation during the course of the second millennium.

The myth

Three copies from Nippur provide a subscript labeling it a šìr-gíd-da, or "long song", of Ninurta,[1] where the term long perhaps refers to the tuning of the musical instrument intended to accompany the song.[2] It is extant in unilingual Sumerian from Nippur during the Old Babylonian period, and thereafter in bilingual editions from the Kassite, middle Assyrian and neo-Assyrian and neo-Babylonian versions, where the later ones are closer textually to the old version than the Middle Babylonian.[3] Along with its companion composition, Lugal-e, it is the only Sumerian composition other than incantations and proverbs to have survived in the canon from the Old Babylonian period into the first Millennium.[2] The title comes from the opening line: "an-[gim] dím-ma, den-líl-gim dím-ma", "created like An, created like Enlil".

The narrative relates that he mounts the monsters, “slain heroes,” he has defeated as trophies on his [gišgigir z]a-gìn-na, “shining chariot.” Echoing the number of Tiāmat’s eleven monstrous offspring, (from the Enûma Eliš, whom Marduk had vanquished), Ninurta’s conquests included

- wild bulls he hung on the axle,

- captured cows on the cross-piece of the yoke,

- a six-headed Wild Ram (šeg.SAG-ÀŠ) on the dustguard,

- Bašmu (Sumerian: Usum) on the seat,

- Magilum, or "ship-locust," on the frame,

- the bison Kusarikku (Sumerian: gud.alim) on the beam,

- the mermaid Kulianna on the footboard,

- “white substance” (gaṣṣa, gypsum[4]), on the forward part of the yoke,

- strong copper (urudû[5] níg kal-ga) on the inside pole pin,

- the Anzu-bird on the front guard and

- the seven-headed serpent (Sumerian: muš sag-imin) possibly Mušmaḫḫū on another illegible part.[2]

He then journeys with his attendants, Udanna, the all-seeing god, Lugalanbadra, the bearded lord, and Lugalkudub, with full battle regalia in a terrifying procession to Nippur. Nusku warns him that he is frightening the gods, the Ananna, and, if he can tone it down a little, Enlil will reward him. In the Ekur, he displays his trophies and booty to the general astonishment of the gods – including his brother, the moon god Sin, father, Enlil, and mother Ninlil. Ninurta then extols his virtues in a long hymn of self-praise in an effort to solicit the establishment of his own cult. On his departure from the Ekur, he is petitioned by the god Ninkarnunna to extend his blessings to the king, perhaps the underlying purpose of the whole poem. The work ends with: d"Ninurta dumu mah é-kur-ra" ("Ninurta, the magnificent scion of Ekur").[6]

The ancient use of the text is uncertain. It may have been recited during some kind of cultic activity, such as the annual transport of the Ninurta idol between the temples, Ešumeša and Ekur.[2]

References

- Gonzalo Rubio (2009). "Sumerian Literature". In Carl S. Ehrlich (ed.). From an Antique Land: An Introduction to Ancient Near Eastern Literature. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 27.

- Jerrold S. Cooper (1978). The return of Ninurta to Nippur: An-gim dím-ma (AnOr 52). Pontificium institutum biblicum. pp. 2–3, 10–13, 53ff.

- William W. Hallo (2009). The World's Oldest Literature: Studies in Sumerian Belles-Lettres. Brill. pp. 60–61.

- gaṣṣa CAD g, p. 54.

- urudû CAD u pp. 269–270.

- Charles Penglase (1994). Greek Myths and Mesopotamia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 55–57.

External links

- Ninurta's return to Nibru: a šir-gida to Ninurta at The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL)