Aida

Aida (Italian: [aˈiːda]) is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Set in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, it was commissioned by Cairo's Khedivial Opera House and had its première there on 24 December 1871, in a performance conducted by Giovanni Bottesini. Today the work holds a central place in the operatic canon, receiving performances every year around the world; at New York's Metropolitan Opera alone, Aida has been sung more than 1,100 times since 1886. Ghislanzoni's scheme follows a scenario often attributed to the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, but Verdi biographer Mary Jane Phillips-Matz argues that the source is actually Temistocle Solera.[1]

| Aida | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Giuseppe Verdi | |

Cover of a very early vocal score, c. 1872 | |

| Librettist | Antonio Ghislanzoni |

| Language | Italian |

| Premiere | |

Elements of the opera's genesis and sources

Isma'il Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, commissioned Verdi to write an opera for performance to celebrate the opening of the Khedivial Opera House, paying him 150,000 francs,[2] but the premiere was delayed because of the Siege of Paris (1870–71), during the Franco-Prussian War, when the scenery and costumes were stuck in the French capital, and Verdi's Rigoletto was performed instead. Aida eventually premiered in Cairo in late 1871. Contrary to popular belief, the opera was not written to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, for which Verdi had been invited to write an inaugural hymn, but had declined.[3] The plot bears striking, though unintentional, similarities to Metastasio's libretto La Nitteti (1756).[3]

Performance history

Cairo premiere and initial success in Italy

Verdi originally chose to write a brief orchestral prelude instead of a full overture for the opera. He then composed an overture of the "potpourri" variety to replace the original prelude. However, in the end he decided not to have the overture performed because of its—his own words—"pretentious insipidity". This overture, never used today, was given a rare broadcast performance by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra on 30 March 1940, but was never commercially issued.[4]

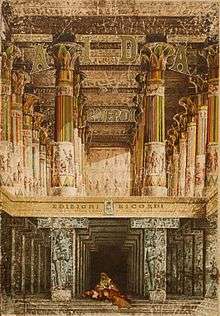

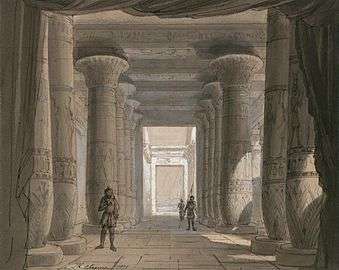

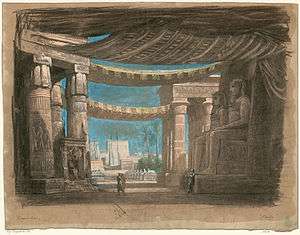

Aida met with great acclaim when it finally opened in Cairo on 24 December 1871. The costumes and accessories for the premiere were designed by Auguste Mariette, who also oversaw the design and construction of the sets, which were made in Paris by the Opéra's scene painters Auguste-Alfred Rubé and Philippe Chaperon (acts 1 and 4) and Édouard Desplechin and Jean-Baptiste Lavastre (acts 2 and 3), and shipped to Cairo.[5] Although Verdi did not attend the premiere in Cairo, he was most dissatisfied with the fact that the audience consisted of invited dignitaries, politicians and critics, but no members of the general public.[6] He therefore considered the Italian (and European) premiere, held at La Scala, Milan on 8 February 1872, and a performance in which he was heavily involved at every stage, to be its real premiere.

Verdi had also written the role of Aida for the voice of Teresa Stolz, who sang it for the first time at the Milan premiere. Verdi had asked her fiancé, Angelo Mariani, to conduct the Cairo premiere, but he declined, so Giovanni Bottesini filled the gap. The Milan Amneris, Maria Waldmann, was his favourite in the role and she repeated it a number of times at his request.[7]

Aida was received with great enthusiasm at its Milan premiere. The opera was soon mounted at major opera houses throughout Italy, including the Teatro Regio di Parma (20 April 1872), the Teatro di San Carlo (30 March 1873), La Fenice (11 June 1873), the Teatro Regio di Torino (26 December 1874), the Teatro Comunale di Bologna (30 September 1877, with Giuseppina Pasqua as Amneris and Franco Novara as the King), and the Teatro Costanzi (8 October 1881, with Theresia Singer as Aida and Giulia Novelli as Amneris) among others.[8]

Other 19th-century performances

Details of important national and other premieres of Aida follow:

- Argentina: 4 October 1873, at the original Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, located at Rivadavia and Reconquista, then replaced by the headquarters of the Bank of the Argentine Nation.

- United States: 26 November 1873, Academy of Music in New York City, with Ostava Torriani in the title role, Annie Louise Cary as Amneris, Italo Campanini as Radamès, Victor Maurel as Amonasro, and Evasio Scolara as the King[9]

- Germany: 20 April 1874, Berlin State Opera, with Mathilde Mallinger as Aida, Albert Niemann as Radamès, and Franz Betz as Amonasro[10]

- Austria: 29 April 1874, Vienna State Opera, with Amalie Materna as Amneris

- Hungary: 10 April 1875, Hungarian State Opera House, Budapest[8]

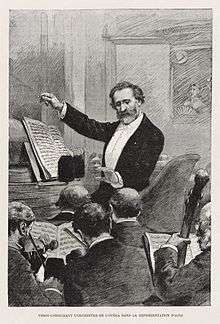

- France: 22 April 1876, Théâtre-Lyrique Italien, Salle Ventadour, Paris, with almost the same cast as the Milan premiere,[8] but with Édouard de Reszke making his debut as the King.[11] This performance was conducted by Verdi.

- United Kingdom: 22 June 1876, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, with Adelina Patti as Aida, Ernesto Nicolini as Radamès, and Francesco Graziani as Amonasro[12]

- Australia: 6 September 1877, Royal Theatre, Melbourne[13]

- Munich: 1877, Bavarian State Opera, with Josephine Schefsky as Amneris[14]

- Stockholm: 16 February 1880, Royal Swedish Opera in Swedish, with Selma Ek in the title role[15][16]

- Palais Garnier, Paris: 22 March 1880, sung in French, with Gabrielle Krauss as Aida, Rosine Bloch as Amnéris, Henri Sellier as Radamès, Victor Maurel as Amonasro, Georges-François Menu as the King, and Auguste Boudouresque as Ramphis.[17]

- Metropolitan Opera, New York: 12 November 1886, conducted by Anton Seidl, with Therese Herbert-Förster (the wife of Victor Herbert) in the title role, Carl Zobel as Radamès, Marianne Brandt as Amneris, Adolf Robinson as Amonasro, Emil Fischer as Ramfis, and Georg Sieglitz as the King.[8]

- Rio de Janeiro: 30 June 1886, Theatro Lyrico Fluminense. During rehearsals at the Theatro Lyrico there was an ongoing quarrel between the performers of the Italian touring opera company and the local inept conductor, with the result that substitute conductors were rejected by the audience. Arturo Toscanini, at the time a 19-year-old cellist who was assistant chorus master, was persuaded to take up the baton for the performance. Toscanini conducted the entire opera from memory, with great success. This would be the start of a promising career.[18][19]

20th century and beyond

A complete concert version of the opera was given in New York City in 1949. Conducted by Toscanini with Herva Nelli as Aida and Richard Tucker as Radamès, it was televised on the NBC television network. Due to the length of the opera, it was divided into two telecasts, preserved on kinescopes, and later released on video by RCA and Testament. The audio portion of the broadcast, including some remakes in June 1954, was released on LP and CD by RCA Victor. Other notable performances from this period include a 1955 performance conducted by Tullio Serafin with Maria Callas as Aida and Richard Tucker as Radamès and a 1959 performance conducted by Herbert von Karajan with Renata Tebaldi as Aida and Carlo Bergonzi as Radamès.[21]

La Scala mounted a lavish new production of Aida designed by Franco Zeffirelli for the opening night of its 2006/2007 season. The production starred Violeta Urmana in the title role and Roberto Alagna as Radamès. Alagna subsequently made the headlines when he was booed for his rendition of "Celeste Aida" during the second performance, walked off the stage, and was dismissed from the remainder of the run. The production continued to cause controversy in 2014 when Zeffirelli protested La Scala's rental of the production to the Astana Opera House in Kazakhstan without his permission. According to Zeffirelli, the move had doomed his production to an "infamous and brutal" fate.[22][23][24]

Aida continues to be a staple of the standard operatic repertoire.[25] It is frequently performed in the Verona Arena, and is a staple of its renowned opera festival.[26]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 24 December 1871[27] Cairo (Conductor: Giovanni Bottesini) |

European premiere 8 February 1872[28] La Scala, Milan (Conductor: Franco Faccio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aida, an Ethiopian princess | soprano | Antonietta Anastasi-Pozzoni | Teresa Stolz |

| The King of Egypt | bass | Tommaso Costa | Paride Pavoleri |

| Amneris, daughter of the King | mezzo-soprano | Eleonora Grossi | Maria Waldmann |

| Radamès, Captain of the Guard | tenor | Pietro Mongini | Giuseppe Fancelli |

| Amonasro, King of Ethiopia | baritone | Francesco Steller | Francesco Pandolfini |

| Ramfis, High Priest | bass | Paolo Medini | Ormando Maini |

| A messenger | tenor | Luigi Stecchi-Bottardi | Luigi Vistarini |

| Voice of the High Priestess[29] | soprano | Marietta Allievi | |

| Priests, priestesses, ministers, captains, soldiers, officials, Ethiopians, slaves and prisoners, Egyptians, animals and chorus | |||

Instrumentation

3 flutes (3rd also piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, triangle, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, harp, strings; on-stage banda: 6 Egyptian trumpets ("Aida trumpets"), military band, harp[30]

Setting

The libretto does not specify a precise time period, so it is difficult to place the opera more specifically than the Old Kingdom.[31] For the first production, Mariette went to great efforts to make the sets and costumes authentic.[32] Given the consistent artistic styles throughout the 3000-year history of ancient Egypt, a given production does not particularly need to choose a specific time period within the larger frame of ancient Egyptian history.[31]

Synopsis

Backstory: The Egyptians have captured and enslaved Aida, an Ethiopian princess. An Egyptian military commander, Radamès, struggles to choose between his love for her and his loyalty to the King of Egypt. To complicate the story further, the King's daughter Amneris is in love with Radamès, although he does not return her feelings.

Act 1

Scene 1: A hall in the King's palace; through the rear gate the pyramids and temples of Memphis are visible

Ramfis, the high priest of Egypt, tells Radamès, the young warrior, that war with the Ethiopians seems inevitable, and Radamès hopes that he will be chosen as the Egyptian commander (Ramfis, Radamès: "Sì, corre voce l'Etiope ardisca" / Yes, it is rumored that Ethiopia dares once again to threaten our power).

Radamès dreams both of gaining victory on the battlefield and of Aida, an Ethiopian slave, with whom he is secretly in love (Radamès: "Se quel guerrier io fossi! ... Celeste Aida" / Heavenly Aida). Aida, who is also secretly in love with Radamès, is the captured daughter of the Ethiopian King Amonasro, but her Egyptian captors are unaware of her true identity. Her father has invaded Egypt to deliver her from servitude.

Amneris, the daughter of the Egyptian King, enters the hall. She too loves Radamès, but fears that his heart belongs to someone else (Radamès, Amneris: "Quale insolita gioia nel tuo sguardo" / In your looks I trace a joy unwonted).

Aida appears and, when Radamès sees her, Amneris notices that he looks disturbed. She suspects that Aida could be her rival, but is able to hide her jealousy and approach Aida (Amneris, Aida, Radamès: "Vieni, o diletta, appressati" / Come, O delight, come closer).

The King enters, along with the High Priest, Ramfis, and the whole palace court. A messenger announces that the Ethiopians, led by King Amonasro, are marching towards Thebes. The King declares war and proclaims that Radamès is the man chosen by the goddess Isis to be the leader of the army (The King, Messenger, Radamès, Aida, Amneris, Ramfis, chorus: "Alta cagion v'aduna .. Guerra, guerra, guerra!" / Oh fate o'er Egypt looming .. War, war, war!). Upon receiving this mandate from the King, Radamès proceeds to the temple of Vulcan to take up the sacred arms (The King, Radamès, Aida, Amneris, chorus: "Su! del Nilo al sacro lido" .. (reprise) "Guerra, guerra guerra!" / On! Of Nilus' sacred river, guard the shores .. (reprise) War, war, war!).

Alone in the hall, Aida feels torn between her love for her father, her country, and Radamès (Aida: "Ritorna vincitor" / Return a conqueror).

Scene 2: Inside the Temple of Vulcan

Solemn ceremonies and dances by the priestesses take place (High Priestess, chorus, Radamès: "Possente Ftha ... Tu che dal nulla" / O mighty Ptah). This is followed by the installation of Radamès to the office of commander-in-chief (High Priestess, chorus, Ramfis, Radamès: "Immenso Ftha .. Mortal, diletto ai Numi" / O mighty one, guard and protect!). All present in the temple pray fervently for the victory of Egypt and protection for their warriors ("Nume, custode e vindice"/ Hear us, O guardian deity).

Act 2

Scene 1: The chamber of Amneris

Dances and music to celebrate Radamès' victory take place (Chorus, Amneris: "Chi mai fra gli inni e i plausi" / Our songs his glory praising). However, Amneris is still in doubt about Radamès' love and wonders whether Aida is in love with him. She tries to forget her doubt, entertaining her worried heart with the dance of Moorish slaves (Chorus, Amneris: "Vieni: sul crin ti piovano" / Come bind your flowing tresses).

When Aida enters the chamber, Amneris asks everyone to leave. By falsely telling Aida that Radamès has died in the battle, she tricks her into professing her love for him. In grief, and shocked by the news, Aida confesses that her heart belongs to Radamès eternally (Amneris, Aida: "Fu la sorte dell'armi a' tuoi funesta" / The battle's outcome was cruel for your people).

This confession fires Amneris with rage, and she plans on taking revenge on Aida. Ignoring Aida's pleadings (Amneris, Aida, chorus: "Su! del Nilo al sacro lido" / Up! at the sacred shores of the Nile), Amneris leaves her alone in the chamber.

Scene 2: The grand gate of the city of Thebes

Radamès returns victorious and the troops march into the city (Chorus, Ramfis: "Gloria all'Egitto, ad Iside" / Glory to Egypt, [and] to Isis!).

The Egyptian king decrees that on this day the triumphant Radamès may have anything he wishes. The Ethiopian captives are led onstage in chains, Amonasro among them. Aida immediately rushes to her father, who whispers to her to conceal his true identity as King of Ethiopia from the Egyptians. Amonasro deceptively proclaims to the Egyptians that the Ethiopian king (referring to himself) has been slain in battle. Aida, Amonasro, and the captured Ethiopians plead with the Egyptian King for mercy, but Ramfis and the Egyptian priests call for their death (Aida, Amneris, Radamès, The King, Amonasro, chorus: "Che veggo! .. Egli? .. Mio padre! .. Anch'io pugnai .. Struggi, o Re, queste ciurme feroci" / What do I see?.. Is it he? My father? .. Destroy, O King, these ferocious creatures).

Claiming the reward promised by the King of Egypt, Radamès pleads with him to spare the lives of the prisoners and to set them free. The King grants Radamès' wish, and declares that he (Radamès) will be his (the King's) successor and will marry the King's daughter (Amneris). (Aida, Amneris, Radamès, Ramfis, The King, Amonasro, chorus: "O Re: pei sacri Numi! .. Gloria all'Egitto" / O King, by the sacred gods ... Glory to Egypt!). At Ramfis' suggestion to the King, Aida and Amonasro remain as hostages to ensure that the Ethiopians do not avenge their defeat.

Act 3

On the banks of the Nile, near the Temple of Isis

Prayers are said (Chorus, High Priestess, Ramfis, Amneris: "O tu che sei d'Osiride" / O thou who to Osiris art) on the eve of Amneris and Radamès' wedding in the Temple of Isis. Outside, Aida waits to meet with Radamès as they had planned (Aida: "Qui Radamès verra .. O patria mia" / Oh, my dear country!).

Amonasro appears and orders Aida to find out the location of the Egyptian army from Radamès. Aida, torn between her love for Radamès and her loyalty to her native land and to her father, reluctantly agrees. (Aida, Amonasro: "Ciel, mio padre! .. Rivedrai le foreste imbalsamate" / Once again shalt thou gaze). When Radamès arrives, Amonasro hides behind a rock and listens to their conversation.

Radamès affirms that he will marry Aida ("Pur ti riveggo, mia dolce Aida .. Nel fiero anelito"; "Fuggiam gli ardori inospiti .. Là, tra foreste vergini" / I see you again, my sweet Aida!), and Aida convinces him to flee to the desert with her.

In order to make their escape easier, Radamès proposes that they use a safe route without any fear of discovery and reveals the location where his army has chosen to attack. Upon hearing this, Amonasro comes out of hiding and reveals his identity. Radamès realizes, to his extreme dismay, that he has unwittingly revealed a crucial military secret to the enemy. At the same time, Amneris and Ramfis leave the temple and, seeing Radamès in conference with the enemy, call for the imperial guards. Amonasro draws a dagger, intending to kill Amneris and Ramfis before the guards can hear them, but Radamès disarms him, quickly orders him to flee with Aida, and surrenders himself to the imperial guards as Aida and Amonasro run off. The guards arrest him as a traitor.

Act 4

Scene 1: A hall in the Temple of Justice. To one side is the door leading to Radamès' prison cell

Amneris desires to save Radamès ("L'aborrita rivale a me sfuggia" / My hated rival has escaped me). She calls for the guard to bring him to her.

She asks Radamès to deny the accusations, but Radamès, who does not wish to live without Aida, refuses. He is relieved to know Aida is still alive and hopes she has reached her own country (Amneris, Radamès: "Già i Sacerdoti adunansi" / Already the priests are assembling).

Offstage, Ramfis recites the charges against Radamès and calls on him to defend himself, but he stands mute, and is condemned to death as a traitor. Amneris, who remains onstage, protests that Radamès is innocent, and pleads with the priests to show mercy. The priests sentence him to be buried alive; Amneris weeps and curses the priests as he is taken away (Judgment scene, Amneris, Ramfis, and chorus: "Ahimè! .. morir mi sento .. Radamès, e deciso il tuo fato" / Alas .. I feel death .. Radamès, your fate is decided).

Scene 2: The lower portion of the stage shows the vault in the Temple of Vulcan; the upper portion represents the temple itself

Radamès has been taken into the lower floor of the temple and sealed up in a dark vault, where he thinks that he is alone. As he hopes that Aida is in a safer place, he hears a sigh and then sees Aida. She has hidden herself in the vault in order to die with Radamès (Radamès: "La fatal pietra sovra me si chiuse" / The fatal stone now closes over me). They accept their terrible fate (Radamès: "Morir! Si pura e bella" / To die! So pure and lovely!) and bid farewell to Earth and its sorrows (duet "O terra addio").[33] Above the vault in the temple of Vulcan, Amneris weeps and prays to the goddess Isis. In the vault below, Aida dies in Radamès' arms as the priests, offstage, pray to the god Ptah. (Chorus, Aida, Radamès, Amneris: "Immenso Ftha" / Almighty Ptah).

Adaptations

The opera has been adapted for motion pictures on several occasions, most notably in a 1953 production which starred Lois Maxwell as Amneris and Sophia Loren as Aida, and a 1987 Swedish production. In both cases, the lead actors lip-synched to recordings by actual opera singers. In the case of the 1953 film, Ebe Stignani sang as Amneris, while Renata Tebaldi sang as Aida. The opera's story, but not its music, was used as the basis for a 1998 musical of the same name written by Elton John and Tim Rice.

Recordings

References

Notes

- Phillips-Matz, pp. 570–573

- Greene 1985, p. .

- The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, accessed through Oxford Music Online

- Frank 2002, p. 28.

- Auguste Mariette to Paul Draneht (General Manager of the Cairo Opera House), Paris, 28 September 1871. (Translated and annotated), Busch 1978, pp. 224–225.

- The Cairo Opera House could only hold 850 spectators (Pitt & Hassan 1992).

- Verdi's Falstaff in Letters and Contemporary Reviews on questia-online-library.com (subscription required)

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Aida performance history". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- McCants, Clyde (2005). Verdi's Aida: A Record of the Life of the Opera On and Off the Stage. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786423286.

- Busch 1978, p. .

- Phillips-Matz 1993, p. 628.

- David Kimbell, in Holden, p. 983

- Irvin

- "Biography of Josephine Schefsky at theaterspielen.ch (in German)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- Ek Biography at operissimo.com (in German) Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Loewenberg 1978, column 1019 (exact date, language).

- Wolff 1962, p. 27; Phillips-Matz 1993, pp. 652–653.

- Tarozzi, p. 36

- Nicotra,

- Collins, Liat (4 June 2011). "Conquering Masada". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- OCLC 807743126; OCLC 65964014

- Christiansen, Rupert (9 December 2006). "Zeffirelli's triumphant Aida at La Scala". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- BBC News (11 December 2006). "Booed tenor quits La Scala's Aida". Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Day, Michael (9 October 2014). "Franco Zeffirelli takes on La Scala: Legendary opera director in battle with theatre over sale of one of his 'greatest' productions to Kazakhstan". The Independent. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Operabase. Performances during the 2008/09 to 2012/13 seasons. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "Aida alla recita 14 per l'opera Festival 2018" (in Italian). Economic Veronese. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Budden 1984, p. 160.

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Aida, 8 February 1872". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- The High Priestess's name was Termuthis in early documentation.

- The music of Aida, Utah Opera, 7 March 2016

- "Aida and Ancient Egyptian History on the Met Opera website". Archived from the original on 2003-05-03.

- Weisgall, The New York Times

- The original draft included a speech by Aida (excised from the final version) that explained her presence beneath the Temple: "My heart knew your sentence. For three days I have waited here." The line most familiar to audiences translates as: "My heart forewarned me of your condemnation. In this tomb that was opened for you I entered secretly. Here, away from human sight, in your arms I wish to die."

Cited sources

- Budden, Julian (1984). The Operas of Verdi, Volume 3: From Don Carlos to Falstaff. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-30740-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Busch, Hans (1978). Verdi's Aida. The History of an Opera in Letters and Documents. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0798-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (hardcover); ISBN 978-0-8166-5715-5 (paperback).

- Frank, Morton H. (2002). Arturo Toscanini: The NBC Years. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 1-57467-069-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greene, David Mason (1985). Greene's Biographical Encyclopedia of Composers. Reproducing Piano Roll Fnd. ISBN 0-385-14278-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Irvin, Eric (1985). Dictionary of the Australian Theatre, 1788–1914, Sydney: Hale & Iremonger. ISBN 0-86806-127-1 ISBN 0-86806-127-1

- Kimbell, David (2001), in Holden, Amanda, editor (2001), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

- "Aida" in The Oxford Dictionary of Music, (Ed.) Michael Kennedy. 2nd ed. rev., (Accessed 19 September 2010) (subscription required)

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1978). Annals of Opera 1597–1940 Totowa, New Jersey: Rowman and Littlefield. (third edition, revised.) ISBN 978-0-87471-851-5.

- Melitz, Leo (1921). The Opera Goer's Complete Guide. Dodd, Mead and Company. (Source of synopsis with updating to its language)

- Nicotra, Tobia (2005). Arturo Toscanini. Kessinger Publ. Co. ISBN 978-1-4179-0126-5.

- Osborne, Charles (1969). The Complete Operas of Verdi, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc. ISBN 0-306-80072-1

- Parker, Roger (1998). "Aida", in Stanley Sadie, (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. 1. London: Macmillan Publishers, Inc. 1998 ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (1993). Verdi: A Biography, London & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-313204-4.

- Pitt, Charles; Hassan, Tarek H. A. (1992). "Cairo" in Sadie 1992, vol. 1, p. 682.

- Simon, Henry W. (1946). A Treasury of Grand Opera. Simon and Schuster, New York, New York.

- Tarozzi, Giuseppe (1977). Non muore la musica – La vita e l'opera di Arturo Toscanini. Sugarco Edizioni.

- Weisgall, Deborah. "Looking at Ancient Egypt, Seeing Modern America", The New York Times, 14 November 1999. Retrieved 2 July 2011

- Wolff, Stéphane (1962). L'Opéra au Palais Garnier (1875–1962). Paris: Deposé au journal L'Entr'acte OCLC 7068320, 460748195. Paris: Slatkine (1983 reprint) ISBN 978-2-05-000214-2.

Other sources

- De Van, Gilles (trans. Gilda Roberts) (1998). Verdi's Theater: Creating Drama Through Music. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14369-4 (hardback), ISBN 0-226-14370-8 (paperback)

- Forment, Bruno (2015). "Staging Verdi in the Provinces: The Aida Scenery of Albert Dubosq", in Staging Verdi and Wagner, ed. Naomi Matsumoto (pp. 263–286). Turnhout: Brepols.

- Gossett, Philip (2006). Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30482-5

- Martin, George Whitney (1963). Verdi: His Music, Life and Times. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. ISBN 0-396-08196-7

- Parker, Roger (2007). The New Grove Guide to Verdi and His Operas, Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531314-7

- Pistone, Danièle (1995). Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera: From Rossini to Puccini, Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-82-9

- Rous, Samual Holland (1924). The Victrola Book of the Opera: Stories of One Hundred and Twenty Operas with Seven-Hundred Illustrations and Descriptions of Twelve-Hundred Victor Opera Records. Victor Talking Machine Co.

- Toye, Francis (1931). Giuseppe Verdi: His Life and Works, New York: Knopf.

- Walker, Frank (1982). The Man Verdi. New York: Knopf, 1962, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87132-0

- Wells, John (2009). "Aida". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8117-3.

- Warrack, John and West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Opera New York: OUP. ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Werfel, Franz and Stefan, Paul (1973). Verdi: The Man and His Letters, New York, Vienna House. ISBN 0-8443-0088-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aida (opera). |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Aida: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Opera Guide, Synopsis – Libretto – Highlights

- "Opera in a nutshell" Soundfiles (MIDI)

- Complete libretto of the opera

- Score

- Aria Database list of arias

- Further Aida discography

- San Diego OperaTalk! with Nick Reveles: Verdi's Aida

- Aida by Antonio Ghislanzoni, music by Giuseppe Verdi (1871), Online Library of Liberty