Amasa Holcomb

Amasa Holcomb (1787–1875) was an American farmer, surveyor, civil engineer, businessman, and manufacturer of surveying instruments and telescopes.[1]

Amasa Holcomb | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 18, 1787 |

| Died | March 1875 |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | self-taught |

| Occupation | businessman |

| Known for | first American maker of telescopes |

| Spouse(s) | Gillett Kendall, m. 1808 |

| Parent(s) | Elijah Holcomb Junior, d. 1841 Lucy Holcomb, b. 1767 d. 1800 |

| Relatives | Paternal grandparents: Elijah Holcomb and Violet Cornish Maternal grandparents: Silas Holcomb and Mary Post |

Early life

Holcomb grew up in Southwick, Massachusetts, the son of Elijah Holcomb and Lucy Holcomb, and a descendant of the immigrant Thomas Holcomb. There were no schools in his district, so he didn't have formal schooling, but gave himself an education. He studied books on geometry, navigation, optics and astronomy that were previously owned by his uncle Abijah, who was lost at sea. At fifteen years of age Holcomb became a tutor at a private school in Suffield, Connecticut, teaching college preparatory courses to students older than himself.[1]

Mid life

Holcomb went into the business of surveying land about 1808 since he was familiar with optics and associated equipment. For a while he also did private tutoring in the fields of surveying, optics, and astronomy. In the 1820s he manufactured many sets of surveyors' instruments. His buyers were his students as well as other civil engineers.[1]

Holcomb wrote his own almanac in 1807 and 1808, when he was twenty-one years old, because he found Nehemiah Strong's almanac was in need of much improvement. It did not predict the 1806 solar eclipse that he viewed on January 4 of that year. Holcomb had made astronomical computations from the books he had on hand and predicted this eclipse himself. Holcomb observed the eclipse with instruments he had made himself.[1]

Sometime around 1810 he decided to fabricate surveying instruments, selling chains, compasses, and small transit telescopes. He also fabricated for sale magnets, electrical apparatus and leveling instruments. He was quite successful in the surveying trade, however left it in 1825 and went into civil engineering.[1]

Holcomb’s telescopes

Holcomb fabricated the first telescopes manufactured in the United States.[2] The first reflecting telescope Holcomb made to order was for John A. Fulton of Chillicothe, Ohio, about 1826. It was fourteen feet long with a ten-inch (254 mm) aperture with six eye pieces with a magnification of from 90 to 960 times. He fabricated and manufactured telescopes in earnest soon thereafter, probably around 1828,[3] which marked the first such manufacturing business in the United States.[1] He enjoyed making telescopes and at the beginning of his manufacturing venture he never thought of it ever becoming a profitable business, just a labor of love.[1]

The telescopes he made were in four sizes:

- fourteen feet long with a ten-inch (254 mm) aperture

- ten feet long with an eight-inch (203 mm) aperture

- seven and a half feet long with a six-inch (152 mm) aperture

- five feet long with a four-inch (102 mm) aperture

In 1830 Holcomb brought an achromatic telescope to Professor Benjamin Silliman at Yale University in New Haven. After inspection the professor ordered one for Yale University and published a notice of it in the American Journal of Science.[3] Around 1833 he began to get orders for his telescopes. Holcomb's telescopes in 1834, 1835, and 1836 were inspected by a committee at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia and granted awards for their outstanding workmanship. On the committee to examine his telescopes were Robert M. Patterson (director of the United States Mint), Alexander D. Bach (superintendent of the Coast survey), Dr Robert Hare (chemist), Sears Cook Walker, James Pollard Espy, and Isiah T. Lukens.[4] In 1834, he was awarded the John Scott award, presented by the City of Philadelphia, under the recommendation of the Franklin Institute.[5]

Holcomb's 8.5-inch (0.22 m) telescope fabricated in 1835 was the largest telescope in America in its day. Institutional customers of Holcomb's were Brown University, Delaware College, and Williston Academy. A telescope of Holcomb's went to the East Indies and one to the Hawaiian Islands. Holcomb remained the only telescope maker in the United States until Henry Fitz and Alvan Clark began making refractor telescopes. Holcomb retired from telescope making in 1846.[1]

Smithsonian

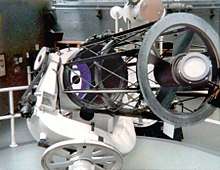

Two telescopes manufactured by Holcomb were donated by Holcomb's descendants to the Smithsonian Institution in 1933. Until then they were in the attic of the family home in Southwick, Massachusetts.[1]

- Herschelian reflector, 8.5-inch (220 mm) aperture, 9 feet 4 inches (2.84 m) in length, shown at the Franklin Institute in 1835, USNM 310598.

- Transit telescope, 1.5-inch (38 mm) refractor, 21 inches in length, mounted on a 14-inch (360 mm) cross tube with graduated circle, but lacking the base, USNM 310599.

Other aspects of his life

In 1816 Holcomb was chosen a "father" in his town he lived in. He held a city office position there during four successive years and occasionally by subsequent elections. In 1832 he was chosen to represent the town in the Legislature of Massachusetts. In 1852 Holcomb was elected to the State senate.[1]

He served three terms in the Massachusetts legislature, was a Justice of the Peace for the county of Hampden for over 50 years, and had been a Methodist minister since 1831, preaching until he was 80 years old. Holcomb was also a trustee of Wesleyan University. In 1837 he received from Williams College the Honorary degree of A.M.

Holcomb died when he was 87 years old in March 1875.[1]

Asteroid 45512 Holcomb, discovered by astronomers with the Catalina Sky Survey in 2000, was named after him.[6] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 8 November 2019 (M.P.C. 118220).[7]

Notes

- "Amasa Holcomb, autobiography". Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- "He was the first that sold a telescope of American manufacture.". Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- Loomis, p. 376

- Journal of the Franklin Institute, volume 14, p. 169, volume 16, p. 11, and volume 18, p. 312

- The Franklin Institute Awards - Laureate Database page on Amasa Holcomb

- "(45512) Holcomb". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

Primary sources

- Holcomb, Amasa. Autobiography written in 1867 when he was 80 years old.

- Holcomb, Amasa. (Almanac for 1807.) Kept at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Holcomb, Amasa. Handwritten text, believed to be autobiographical, unsigned and undated; kept at the Smithsonian Institution. (Reprinted in Holcomb, Fitz, and Peate)

- Holcomb, Amasa. Manuscript notebook kept by Holcomb between 1834 and 1841, on meteorology and astronomy. The Smithsonian Institution, U.S. National Museum catalog 310600.

- Holcomb, Fitz, and Peate: Three 19th Century American Telescope Makers. Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology. United States National Museum Bulletin 228. Washington, D.C., 1962. Introduction, Robert Multhauf.

- "Report on Amasa Holcomb's Reflecting Telescope," Journal of the Franklin Institute, July 1834, new series vol. 14 (whole no. 18), pp. 169–172. (Reprinted in Holcomb, Fitz, and Peate)

- "Report on Holcomb's Reflecting Telescopes," Journal of the Franklin Institute, July 1835, new series vol. 16 (whole no. 20), pp. 11–13. (Reprinted in Holcomb, Fitz, and Peate)

- "Report on Holcomb's Telescope," Journal of the Franklin Institute, August 1836, new ser. vol. 18, whole no. 22, p110)

- "Report on Holcomb's Telescope", American Journal of Science and Arts, various issues, between 1833 and 1836.

Secondary sources

- Davis, Maud Etta Gillett. Historical Facts and Stories About Southwick. July, 1951. Unpublished manuscript kept at Southwick Public Library. (Davis, great grand daughter of Holcomb.)

- Der Bagdasarian, Nicholas. "Amasa Holcomb: Yankee Telescope Maker." Sky & Telescope, June, 1986, p620-622.

- Loomis, Elias, The Recent Progress of Astronomy, Especially the United States, Harper & Brothers, 1856