Henry Fitz

Henry Fitz was a notable American telescope manufacturer.[1]

Henry Fitz | |

|---|---|

self-portrait, 1839 | |

| Born | 31 December 1808 |

| Died | 6 November 1863 (aged 54) |

| Resting place | New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | businessman |

| Known for | manufacturer of telescopes |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Ann Wells m. June 1844. |

Early life

Fitz was born in 1808 in Newburyport, Massachusetts. The family moved to Albany, New York, some eleven years later and to New York City later on. Fitz as a boy was already very interested in science and mechanics. He initially learned the printing trade from his father. They printed the religious weekly publication called "The Gospel Herald". With his mechanical ability he learned the locksmith trade. One of the many hobbies he enjoyed was astronomy. In the 1830s Fitz was already well known as an amateur astronomer when he was a boy. His first telescope was made using a lens from a pair of eyeglasses when he was fifteen years old.[1]

Mid life

Fitz knew Alexander Wolcott, who was working on a speculum mirror for a Cassegrain reflector in the early 1830s. Fitz was able to obtain the half-finished blank that Wolcott had done. He then completed the mirror in 1837 to make a telescope.[1]

Fitz traveled to Europe from August to November 1839 learning astronomical and photographic optics. He learned the French were the best makers of high quality glass. The English and German opticians taught Fitz the techniques of sawing and grinding glass. By the 1840s Fitz had turned his amateur astronomer hobby into a successful business building telescopes.[1]

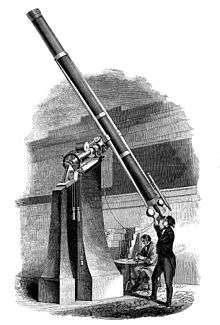

Fitz pioneered techniques of correcting poor quality glass which made him one of the first important American telescope makers. He was the first American to make very large professional refracting telescopes.[2] Fitz made the largest refractor telescopes in America, five different times.[3]

Fitz made forty percent of all the telescopes sold in the United States from 1840 to 1855. He also manufactured eighty percent of all astronomical telescopes made in the United States at this time. American made telescopes were significantly less expensive than comparable instruments from Europe. Manufacturing locally in the United States instead of Europe was an important factor in the proliferation of observatories in the nineteenth century in America.[1]

Fitz contributed considerably in the development of astronomical photography. Making telescopes and related astronomical components was a labor of love for him. Often he would be found working after midnight. He was the best known American maker of telescopes and achromatic instruments before the Civil War.[4] Fitz was in partnership with Wolcott and developed a patented Daguerrotype camera. They had a photographic studio in Baltimore in 1841. Fitz invented and built foot power machines for the grinding of lenses. He also had employees do all the other tasks involved and trained them accordingly in the process of making lenes and mirrors. The critical final mirror polishing he did himself, however, and did not allow his employees to do that. Fitz made a six-inch (152 mm) refractor telescope in 1845 for the American Institute Fair for which he received a gold medal.[1]

The South Carolina College at Columbia in 1851 bought a 6.375-inch (161.9 mm) telescope form Fitz for $1,200. The telescope was used by the college for the next decade. After the Civil War it was stolen for scrap brass. The Haverford College in Pennsylvania purchased an eight-inch (203 mm) refractor telescope from Fitz in 1852. The West Point Academy purchased from Fitz in 1856 a 9.75-inch (248 mm) refractor telescope costing $5,000.[1]

Later life and death

After his death his wife recalled Fitz making doublet lenses, with the flint element ground from the bottom of a tumbler and the crown element made from plate glass. The original workshop of Fitz’s is now in storage at the U.S. National Museum of American History.[1]

Fitz’s telescope business was successful, so in 1863 he was in the process of building a new house. Fitz, however, died suddenly at the end of the year. Some have reported that the cause was when a large chandelier fell from the ceiling of his new home. Obituaries report, however, his demise was from tuberculosis.[1] Before his final illness and death, he was about to sail for Europe to select a glass for a 24-inch (610 mm) telescope, and to procure patents for a camera involving a new form of lens.[5]

Notes

- Abrahams, 1994.

- The Observatory, 1888: Henry Fitz, of New York, is credited with being the first American who obtained special distinction for the manufacture of refractors; he constructed 30 with object-glasses varying from 6 to 16 inches (410 mm) in diameter.

- Abrahams, 1994: Fitz was the first important American telescope maker because his pioneering techniques of local correction of poor quality glass allowed him to construct the largest American made refractor on five different occasions.

- Lankford, p. 211

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Bibliography

- Abrahams, Peter; “Henry Fitz, American telescope maker,” Journal of the Antique Telescope Society, v. 6, 1994.

- Lankford, John; History of Astronomy: An Encyclopedia, published by Taylor & Francis, 1997, ISBN 0-8153-0322-X

- The Observatory by NASA Astrophysics Data System Abstract Service, Royal Greenwich Observatory, published by editors of The Observatory, 1888

- Sperling, Norman; Fair Play for Fitz: Henry Fitz Introduces the All-American Telescope. Rittenhouse, v. 3, no. 2 (Feb. 1989).

- Bell, Trudy; In the Shadow of Giants: Forgotten Nineteenth Century American Telescope Makers and Their Crucial Role in Popular Astronomy. Griffith Observer, Sept. 1986

- Howell, Julia Fitz; Henry Fitz, 1808-1863. Holcomb, Fitz, and Peate: Three 19th Century American Telescope Makers. U.S. National Museum Bulletin 228, 1962

- The Griffith Observer, by Griffith Observatory, published by Griffith Observatory, 1939, Item notes: v.49-50