Alphabetic numeral system

An alphabetic numeral system is a type of numeral system. Developed in classical antiquity, it flourished during the early Middle Ages.[1] In alphabetic numeral systems, numbers are written using the characters of an alphabet, syllabary, or another writing system. Unlike acrophonic numeral systems, where a numeral is represented by the first letter of the lexical name of the numeral, alphabetic numeral systems can arbitrarily assign letters to numerical values. Some systems, including the Arabic, Georgian and Hebrew systems, use an already established alphabetical order.[2] Alphabetic numeral systems originated with Greek numerals around 600 BC and became largely extinct by the 16th century.[3] After the development of positional numeral systems like Hindu–Arabic numerals, the use of alphabetic numeral systems dwindled to predominantly ordered lists, pagination, religious functions, and divinatory magic.[4]

History

The first attested alphabetic numeral system is the Greek alphabetic system (named the Ionic or Milesian system due to its origin in west Asia Minor). The system's structure follows the structure of the Egyptian demotic numerals; Greek letters replaced Egyptian signs. The first examples of the Greek system date back to the 6th century BC, written with the letters of the archaic Greek script used in Ionia.[5]

Other cultures in contact with Greece adopted this numerical notation, replacing the Greek letters with their own script; these included the Hebrews in the late 2nd century BC. The Gothic alphabet adopted their own alphabetic numerals along with the Greek-influenced script.[6] In North Africa, the Coptic system was developed in the 4th century AD,[7] and the Ge'ez system in Ethiopia was developed around 350 AD.[8] Both were developed from the Greek model.

The Arabs developed their own alphabetic numeral system, the abjad numerals, in the 7th century AD, and used it for mathematical and astrological purposes even as late as the 13th century far after the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.[9] After the adoption of Christianity, Armenians and Georgians developed their alphabetical numeral system in the 4th or early 5th century, while in the Byzantine Empire Cyrillic numerals and Glagolitic were introduced in the 9th century. Alphabetic numeral systems were known and used as far north as England, Germany, and Russia, as far south as Ethiopia, as far east as Persia, and in North Africa from Morocco to Central Asia.

By the 16th century AD, most alphabetic numeral systems had died out or were in little use, displaced by Arabic positional and Western numerals as the ordinary numerals of commerce and administration throughout Europe and the Middle East.[10]

The newest alphabetic numeral systems in use, all of them positional, are part of tactile writing systems for visually impaired. Even though 1829 braille had a simple ciphered-positional system copied from Western numerals with a separate symbol for each digit, early experience with students forced its designer Louis Braille to simplify the system, bringing the number of available patterns (symbols) from 125 down to 63, so he had to repurpose a supplementary symbol to mark letters a–j as numerals. Besides this traditional system, another one was developed in France in the 20th century, and yet another one in the US.

Systems

An alphabetic numeral system employs the letters of a script in the specific order of the alphabet in order to express numerals.

In Greek, letters are assigned to respective numbers in the following sets: 1 through 9, 10 through 90, 100 through 900, and so on. Decimal places are represented by a single symbol. As the alphabet ends, higher numbers are represented with various multiplicative methods. However, since writing systems have a differing number of letters, other systems of writing do not necessarily group numbers in this way. The Greek alphabet has 24 letters; three additional letters had to be incorporated in order to reach 900. Unlike the Greek, the Hebrew alphabet's 22 letters allowed for numerical expression up to 400. The Arabic abjad's 28 consonant signs could represent numbers up to 1000. Ancient Aramaic alphabets had enough letters to reach up to 9000. In mathematical and astronomical manuscripts, other methods were used to represent larger numbers. Roman numerals and Attic numerals, both of which were also alphabetic numeral systems, became more concise over time, but required their users to be familiar with many more signs. Acrophonic numerals do not belong to this group of systems because their letter-numerals do not follow the order of an alphabet.

These various systems do not have a single unifying trait or feature. The most common structure is ciphered-additive with a decimal base, with or without the use of multiplicative-additive structuring for the higher numbers. Exceptions include the Armenian notation of Shirakatsi, which is multiplicative-additive and sometimes uses a base 1,000, and the Greek and Arabic astronomical notation systems.

Numeral signs

The tables below show the alphabetic numeral configurations of various writing systems.

Greek alphabetic numerals – "Ionian" or "Milesian numerals" – (minuscule letters)

units α β γ δ ε ϛ ζ η θ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 tens ι κ λ μ ν ξ ο π ϟ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 hundreds ρ σ τ υ φ χ ψ ω ϡ 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 thousands ͵α ͵β ͵γ ͵δ ͵ε ͵ϛ ͵ζ ͵η ͵θ 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000

Some numbers represented with Greek alphabetic numerals:

- ͵γϡμβ = (3000 + 900 + 40 + 2) = 3942

- χξϛ = (600 + 60 + 6) = 666

units א ב ג ד ה ו ז ח ט 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 tens י כ ל מ נ ס ע פ צ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 hundreds ק ר ש ת 100 200 300 400 thousands 'א 'ב 'ג 'ד 'ה 'ו 'ז 'ח 'ט 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000

The Hebrew writing system has only twenty-four consonant signs, so numbers can be expressed with single individual signs only up to 400. Higher hundreds – 500, 600, 700, 800, and 900 – can be written only with various cumulative-additive combinations of the lower hundreds (direction of writing is right to left):[11]

- תק = (400+100) 500

- תר = (400+200) 600

- תש = (400+300) 700

- תת = (400+400) 800

- תררק = 400+200+200+100 = 900

Armenian numeral signs (minuscule letters):

units ա բ գ դ ե զ է ը թ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 tens ժ ի լ խ ծ կ հ ձ ղ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 hundreds ճ մ յ ն շ ո չ պ ջ 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 thousands ռ ս վ տ ր ց ւ փ ք 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000 ten-thousands օ ֆ 346 = յխզ

Unlike many alphabetic numeral systems, the Armenian system does not use multiplication by 1,000 or 10,000 in order to express higher values. Instead, higher values were written out in full using lexical numerals.[12]

Higher numbers

As the alphabet ended, various multiplicative methods were used for the expression of higher numbers in the different systems. In the Greek alphabetic system, for multiples of 1,000, the hasta sign was placed to the left below a numeral-sign to indicate that it should be multiplied by 1,000.[13]

- β = 2

- ͵β = 2,000

- ͵κ = 20,000

With a second level of multiplicative method – multiplication by 10,000 – the numeral set could be expanded. The most common method, used by Aristarchus, involved placing a numeral-phrase above a large M character (M = myriads = 10,000) to indicate multiplication by 10,000.[14] This method could express numbers up to 100,000,000 (108).

20,704 − (2 ⋅ 10,000 + 700 + 4) could be represented as:

ψδ = 20,704

According to Pappus of Alexandria's report, Apollonius of Perga used another method. In it, the numerals above M = myriads = 10,000 represented the exponent of 10,000. The number to be multiplied by M was written after the M character.[15] This method could express 5,462,360,064,000,000 as:

͵EYZB ͵ΓX ͵FY 100003 × 5462 + 100002 × 3600 + 100001 × 6400

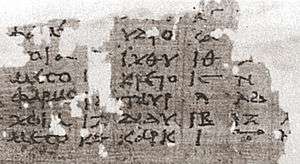

Distinguishing numeral-phrases from text

Alphabetic numerals were distinguished from the words with special signs, most commonly a horizontal stroke above the numeral-phrase, but occasionally with dots placed to either side of it. The latter was manifested in the Greek alphabet with the hasta sign.

![]()

In Ethiopic numerals, known as Geʽez, the signs have marks both above and below them to indicate that their value is numerical. The Ethiopic numerals are the exception, where numeral signs are not letters of their script. This practice became universal from the 15th century onwards.[16]

Numeral signs of Ethiopic numerals with marks both above and below the letters:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 × 1 ፩ ፪ ፫ ፬ ፭ ፮ ፯ ፰ ፱ × 10 ፲ ፳ ፴ ፵ ፶ ፷ ፸ ፹ ፺ × 100 ፻ × 10,000 ፼

The direction of numerals follows the writing system's direction. Writing is from left to right in Greek, Coptic, Ethiopic, Ghotic, Armenian, Georgian, Glagolitic, and Cyrillic alphabetic numerals along with Shirakatsi's notation. Right-to-left writing is found in Hebrew and Syriac alphabetic numerals, Arabic abjad numerals, and Fez numerals.

Fractions

Unit fractions

Unit fractions were a method to express fractions. In Greek alphabetic notation, unit fractions were indicated with the denominator – alphabetic numeral sign – followed by small accents or strokes placed to the right of a numeral, known as a keraia (ʹ). Therefore, γʹ indicated one third, δʹ one fourth, and so on. These fractions were additive and were also known as Egyptian fractions.

For example: δ´ ϛ´ = 1⁄4 + 1⁄6 = 5⁄12.

A mixed number could be written as such: ͵θϡϟϛ δ´ ϛ´ = 9996 + 1⁄4 + 1⁄6

Astronomical fractions

In many astronomical texts, a distinct set of alphabetic numeral systems blend their ordinary alphabetical numerals with a base of 60, such as Babylonian sexagesimal systems. In the 2nd century BC, a hybrid of Babylonian notation and Greek alphabetic numerals emerged and was used to express fractions.[17] Unlike the Babylonian system, the Greek base of 60 was not used for expressing integers.

With this sexagesimal positional system – with a subbase of 10 – for expressing fractions, fourteen of the alphabetic numerals were used (the units from 1 to 9 and the decades from 10 to 50) in order to write any number from 1 through 59. These could be a numerator of a fraction. The positional principle was used for the denominator of a fraction, which was written with an exponent of 60 (60, 3,600, 216,000, etc.). Sexagesimal fractions could be used to express any fractional value, with the successive positions representing 1/60, 1/602, 1/603, and so on.[18] The first major text in which this blended system appeared was Ptolemy's Almagest, written in the 2nd century AD.[19]

Astronomical fractions (with Greek alphabetic signs):

units α β γ δ ε ϛ ζ η θ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 tens ι κ λ μ ν 10 20 30 40 50

͵αφιε κ ιε = 1515 + (20 x 1/60) + (15 x 1/3600) = 1515.3375

This blended system did not use a radix point, but the astronomical fractions had a special sign to indicate zero as a placeholder. Some late Babylonian texts used a similar placeholder. The Greeks adopted this technique using their own sign, whose form and character changed over time from early manuscripts (1st century AD) to an alphabetic notation.[20]

This sexagesimal notation was especially useful in astronomy and mathematics because of the division of the circle into 360 degrees (with subdivisions of 60 minutes per degree and 60 seconds per minute). In Theon of Alexandria's (4th century AD) commentary on the Almagest, the numeral-phrase ͵αφιε κ ιε expresses 1515 (͵αφιε) degrees, 20 (κ) minutes, and 15 (ιε) seconds.[21] The degree's value is in the ordinary decimal alphabetic numerals, including the use of the multiplicative hasta for 1000, while the latter two positions are written in sexagesimal fractions.

Arabs adopted astronomical fractions directly from the Greeks, and similarly Hebrew astronomers used sexagesimal fractions, but Greek numeral signs were replaced by their own alphabetic numeral signs to express both integers and fractions.

Alphabetic numeral systems

- Abjad numerals

- Armenian numerals

- Āryabhaṭa numeration

- Attic numerals

- Coptic numerals

- Cyrillic numerals

- Ethiopic numerals

- Fez numerals

- Glagolitic numerals

- Georgian numerals

- Gothic numerals

- Greek alphabetic

- Hebrew numerals

- Roman numerals

- Shirakatsi's numeral system

- Syriac alphabetic numerals

References

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521878180. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521878180. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521878180. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780521878180. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) pp. 135–138.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 155.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 148.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 152.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p.166.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 185.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 156

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 174.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 138

- Heath, Thomas L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–41.

- Greek number systems – MacTutor

- Ifrah (1998) pp. 246–247.

- Ifrah (1998) p. 156.

- S. Chrisomalis (2010) p. 169)

- Heath (1921) pp. 44–45

- Irani 1955

- Thomas, Ivor. 1962. Selections Illustrating the History of Greek Mathematics, vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 50–51.

Sources

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–187. ISBN 9780521878180.

- Georges Ifrah (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer; translated from the French by David Bellos. London: Harvill Press. ISBN 9781860463242.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Otto Neugebauer (1979). Ethiopic Astronomy and Computus. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Megally, Fuad (1991). Numerical system, Coptic. Coptic Encyclopedia, Azis S. Atiya, ed. New York: Macmillan. pp. 1820–1822..

- Messiha, Heshmat. 1994. Les chiffres coptes. Le Monde Copte 24: 25–28.

- Braune, Wilhelm and Ernst Ebbinghaus. 1966. Gotische Grammatik. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- Gandz, Solomon. 1933. Hebrew numerals. Proceedings of the American Academy of Jewish Research 4: 53–112.

- Millard, A. 1995. Strangers from Egypt and Greece – the signs for numbers in early Hebrew. In Immigration and Emigration within the Ancient Near East, K. van Lerberghe and A. Schoors, eds., pp. 189–194. Leuven: Peeters.

- Colin, G.S. 1960. Abdjad. In Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 1, pp. 97–98. Leiden: Brill.

- Colin, G.S. 1971. Hisab al-djummal. In Encyclopedia of Islam, vol. 3, p. 468. Leiden: Brill.

- Bender, Marvin L., Sydney W. Head, and Roger Cowley. 1976. The Ethiopian writing system. In Language in Ethiopia, M.L. Bender, J.D. Bowen, R.L. Cooper, and CA. Ferguson, eds., pp. 120–129. London: Oxford University Press.

- Shaw, Allen A. 1938–9. An overlooked numeral system of antiquity. National Mathematics Magazine 13: 368–372.

- Cubberley, Paul. 1996. Tlie Slavic alphabets. In The World's Writing Systems, Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, eds., pp. 346–355. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pankhurst, Richard K. P., ed. 1985. Letters from Ethiopian Rulers (Early and Mid-Nineteenth Century), translated by David L. Appleyard and A.K. Irvine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, David E. and L. C Karpinski. 1911. The Hindu-Arabic Numerals. Boston: Ginn

- Gandz, Solomon. 1933. Hebrew numerals. Proceedings of the American Academy of Jewish Research 4: pp. 53–112.

- Schanzlin, G.L. 1934. The abjad notation. The Moslem World 24: 257–261.