Alien 3

Alien 3 (stylized as ALIEN³) is a 1992 American science fiction horror film directed by David Fincher and written by David Giler, Walter Hill, and Larry Ferguson from a story by Vincent Ward. It stars Sigourney Weaver reprising her role as Ellen Ripley. It is the third installment of the Alien franchise.

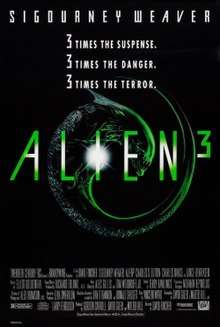

| Alien 3 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Fincher |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Vincent Ward |

| Based on | |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Elliot Goldenthal |

| Cinematography | Alex Thomson |

| Edited by | Terry Rawlings |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50–60 million[2][3][4] |

| Box office | $159.8–$175 million[2][5] |

Set right after the events of Aliens, Ripley and an Alien organism are the only survivors of the Colonial Marine spaceship Sulaco following an escape pod's crash on a planet housing a penal colony populated by violent male inmates. Additional roles are played by Charles Dance, Brian Glover, Charles S. Dutton, Ralph Brown, Paul McGann, Danny Webb, Lance Henriksen, Holt McCallany, Pete Postlethwaite, and Danielle Edmond.

The film faced problems during production, including shooting without a script, with various screenwriters and directors attached. Fincher, in his feature directorial debut, was brought in to direct after a proposed version with Vincent Ward as director was cancelled during pre-production.

Alien 3 was released on May 22, 1992. While it underperformed at the American box office, it earned over $100 million outside North America. The film received mixed reviews and was regarded as inferior to previous installments. Fincher has since disowned the film, blaming studio interference and deadlines. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, seven Saturn Awards (Best Science Fiction Film, Best Actress for Weaver, Best Supporting Actor for Dutton, Best Direction for Fincher, and Best Writing for Giler, Hill, and Ferguson), a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, and an MTV Movie Award for Best Action Sequence. In 2003, a revised version of the film known as the Assembly Cut was released without Fincher's involvement, and received a warmer reception.[6][7][8][9][10]

A sequel, Alien Resurrection, was released in 1997, with Weaver reprising her role as Ripley in the film.

Plot

Following the events of Aliens, a fire starts aboard the Colonial Marine spaceship Sulaco. The computer launches an escape pod containing Ellen Ripley, the young girl Newt, Hicks, and the damaged android Bishop; all four are in cryonic stasis. Scans of the crew's cryotubes show a Queen Facehugger attached to one member. The pod crash-lands on Fiorina "Fury" 161, a foundry and maximum security double-Y chromosome work correctional facility inhabited by male inmates with a genetic mutation which gives the afflicted individual a predisposition for antisocial behavior. The inmates recover the crashed pod and its passengers. The same Facehugger is seen approaching inmate Thomas Murphy's dog, Spike.

Ripley is awakened by Clemens, the prison doctor, who informs her that she is the sole survivor. She is warned by the prison warden, Harold Andrews, that her presence may have disruptive effects. Ripley insists that Clemens perform an autopsy on Newt, secretly fearing that Newt may be carrying an Alien embryo. Despite protests from the warden and his assistant Aaron, the autopsy is conducted and no embryo is found. The bodies of Newt and Hicks are cremated. Elsewhere in the prison, a quadrupedal alien bursts from Spike.

Ripley finds the damaged Bishop in the prison's garbage dump. Just as she is leaving the area, she is cornered by four inmates and almost raped. After being saved by inmate leader Dillon, Ripley returns to the infirmary and re-activates Bishop, who confirms that a Facehugger came with them to Fiorina in the escape pod. Growing to full size, the alien kills Murphy, Boggs, and Rains and returns outcast prisoner Golic to his previously psychopathic state — Golic dubs the creature "the Dragon". Ripley informs Andrews of her previous encounter with the Xenomorphs[11] and suggests everyone work together to hunt down and kill it. The highly skeptical Andrews does not believe her story, and explains that even if she were telling the truth, the facility is without weapons; their only hope is the rescue ship being sent for Ripley by the Weyland-Yutani Corporation.

The Alien ambushes Ripley and Clemens in the prison infirmary, killing him, and almost slays Ripley, but then mysteriously spares her and retreats. Ripley then rushes to the cafeteria to warn the others. Andrews orders Aaron to take her back to the infirmary, but the warden himself is dragged into the vents and killed by the monster. Ripley rallies the inmates and proposes they pour flammable toxic waste into the ventilation system and ignite it to flush out the extraterrestrial. However, its intervention causes a premature explosion and several inmates are killed. With Aaron's help, Ripley scans herself using the escape pod's medical equipment and discovers the embryo of an Alien Queen growing inside her. She also discovers that Weyland-Yutani hopes to turn the aliens into biological weapons.

Deducing that the Alien will not kill her because of the embryo she carries, Ripley begs Dillon to kill her; he agrees only if she helps the inmates kill the Alien first. They form a plan to lure the Alien into the foundry's molding facility, trap it via a series of closing doors, and drown it in molten lead. The bait-and-chase plan results in the deaths of all the remaining prisoners except Dillon and Morse. Dillon sacrifices himself to position the Alien towards the mold as Morse pours the molten lead onto them. Although the alien is covered in molten metal, it escapes the mold but Ripley activates the fire sprinklers, causing its molten metal exoskeleton to cool rapidly and shatter, blowing it apart.

The Weyland–Yutani team arrives, including scientists, heavily armed commandos and a man who looks identical to Bishop,[12] who explains that he is Bishop's creator. He tries to persuade Ripley to undergo surgery to remove the Alien Queen embryo, which he falsely claims will be destroyed. Ripley refuses and steps back onto a mobile platform, which Morse positions over the furnace. The Weyland–Yutani team shoot Morse in the leg in an attempt to stop him; Aaron, believing the Bishop look-alike is an android, strikes the man with a wrench and is killed by the commandos. Ignoring Bishop's pleas to give them the embryo, Ripley throws herself into the furnace, killing herself. The facilities are closed down. Morse, the sole survivor, is led away as Ripley's recording from the first film plays for the final time in the EEV.

Cast

- Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley, reprising her role from the previous two Alien films. Ripley crash-lands on Fiorina 161 and is once again burdened with the task of destroying another of the alien creatures. Sigourney approved of David Twohy's work and signed on, but demanded a larger salary of $4–5 million, plus co-producing credit. She also requested that the action was not to rely on guns.[4]

- Charles S. Dutton as Leonard Dillon, one of Fiorina's inmates who functions as the spiritual and de facto leader amongst the prisoners and attempts to keep the peace in the facility.

- Charles Dance as Jonathan Clemens, a former inmate who now serves as the facility's doctor. He treats Ripley after her escape pod crashes at the start of the film and forms a special bond with her. Before he is killed, Clemens laments to Ripley why he was originally sent to Fiorina, describing it as "more than a little melodramatic." Fincher initially offered the role to Richard E. Grant, hoping to reunite him with Withnail and I co-stars Ralph Brown and Paul McGann.[13]

- Brian Glover as Harold Andrews, the prison warden. He believes Ripley's presence will cause disruption amongst the inmates and attempts to control the rumors surrounding her and the creature. He rejects her claims about the existence of such a creature, only to be killed by it.

- Ralph Brown as Francis Aaron, the assistant of Superintendent Andrews. The prisoners refer to him by the nickname "85", after his IQ score, which annoys him. He opposes Ripley's insistence that the prisoners must try to fight the alien, and repudiates her claim that Weyland–Yutani will collect the alien instead of them.

- Paul McGann as Walter Golic. A mass-murderer and outcast amongst the prison population, Golic becomes very disturbed after being assaulted by the alien in the prison's underground network of tunnels, gradually becoming more and more obsessed with the alien. In the Assembly Cut of the film, his obsession with and defense of the creature lead to murder, and his actions jeopardize the entire plan.

- Danny Webb as Robert Morse, an acerbic, self-centered, and cynical prisoner. Although he is wounded by the Weyland–Yutani team, Morse is the only survivor of the entire incident.

- Lance Henriksen as the voice of the damaged Bishop android, as well as playing a character credited as Bishop II, who appears in the film's final scenes, claiming to be the human designer of the android, who wants the Alien Queen that was growing inside Ripley for use in Weyland-Yutani's bioweapons division. The character is identified as "Michael Bishop Weyland" in tie-in materials to Alien.

- Tom Woodruff Jr. as the alien known as "Dragon".[14] This Alien is different from the ones in previous installments due to its host being quadrupedal (a dog in the theatrical cut, an ox in the assembly cut). Initially a visual effects supervisor, Woodruff decided to take the role of the creature after his company, Amalgamated Dynamics, was hired by Fox.[15] Woodruff said that, following Sigourney Weaver's advice, he approaches the role as an actor instead of a stuntman, trying to make his performance more than "just a guy in a suit." He considered the acting process "as much physical as it is mental."[16]

- Pete Postlethwaite as David Postlethwaite, an inmate smarter than most who is killed by the creature in the bait-and-chase sequence.

- Holt McCallany as Junior, the leader of the group of inmates who attempt to rape Ripley. He has a tattoo of a tear drop underneath his right eye. In the Assembly Cut, he sacrifices himself to trap the alien as redemption.

- Peter Guinness as Peter Gregor, one of the inmates who attempts to rape Ripley, he is bitten in the neck and killed by the Alien during the bait-and-chase sequence.

- Danielle Edmond as Rebecca "Newt" Jorden, the child Ripley forms a maternal bond with in the previous film who briefly returns as a corpse being autopsied. Carrie Henn was unable to reprise her role as Newt as she was too old for the part so Danielle Edmond took over the role in this installment for the brief autopsy scene with Newt's corpse.

- Christopher Fairbank as Thomas Murphy

- Phil Davis as Kevin Dodd

- Vincenzo Nicoli as Alan Jude

- Leon Herbert as Edward Boggs

- Christopher John Fields as Daniel Rains

- Niall Buggy as Eric Buggy

- Hi Ching as Company Man

- Carl Chase as Frank Ellis

- Clive Mantle as Clive William

- DeObia Oparei as Arthur Walkingstick

- Paul Brennen as Yoshi Troy

- Michael Biehn as Corporal Dwayne Hicks (archive picture only)

Development

With the success of Aliens, 20th Century Fox approached Brandywine Productions on further sequels. But Brandywine was less than enthused with an Alien 3 project, with producer David Giler later explaining he and partners Walter Hill and Gordon Carroll wanted to take new directions as "we wouldn't do a reheat of one and two". The trio opted to explore the duplicity of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, and why they were so intent in using the Aliens as biological weapons.[17] Various concepts were discussed, eventually settling on a two-part story, with the treatment for the third film featuring "the underhanded Weyland–Yutani Corporation facing off with a militarily aggressive culture of humans whose rigid socialist ideology has caused them to separate from Earth's society." Michael Biehn's Corporal Hicks would be promoted to protagonist in the third film, with Sigourney Weaver's character of Ellen Ripley reduced to a cameo appearance before returning in the fourth installment, "an epic battle with alien warriors mass-produced by the expatriated Earthlings." Weaver liked the Cold War metaphor, and agreed to a smaller role,[18] particularly due to a dissatisfaction with Fox, who removed scenes from Aliens crucial to Ripley's backstory.[19]

Sigourney Weaver, concerning the future of Ripley.[18]

Although 20th Century Fox were skeptical about the idea, they agreed to finance the development of the story, but asked that Hill and Giler attempt to get Ridley Scott, director of Alien, to make Alien 3. They also asked that the two films be shot back to back to lessen the production costs. While Scott was interested in returning to the franchise, it did not work out due to the director's busy schedule.[18]

1987–1989

In September 1987, Giler and Hill approached cyberpunk author William Gibson to write the script for the third film. Gibson, who told the producers his writing was influenced by Alien, accepted the task. Fearful of an impending strike by the Writers Guild of America, Brandywine asked Gibson to deliver a screenplay by December.[18] Gibson drew heavily from Giler and Hill's treatment, having a strong interest in the "Marxist space empire" element.[20] The following year, Finnish director Renny Harlin was approached by Fox based on his work in A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master.[21] Harlin wanted to go in different directions from the first two movies, having interest in both visiting the Alien homeworld or having the Aliens invading Earth.[17]

Gibson's script was mockingly summed up by him as "Space commies hijack alien eggs—big problem in Mallworld".[18] The story picked up after Aliens, with the Sulaco drifting into an area of space claimed by the "Union of Progressive Peoples". The ship is boarded by people from the U.P.P., who are attacked by a facehugger hiding in the entrails of Bishop's mangled body. The soldiers blast the facehugger into space and take Bishop with them for further study. The Sulaco then arrives at a space station–shopping mall hybrid named Anchorpoint. With Ripley put in a coma, Hicks explores the station and discovers Weyland-Yutani are developing an Alien army. In the meantime, the U.P.P. are doing their own research, which led them to repair Bishop. Eventually Anchorpoint and the U.P.P stations are overrun with the Aliens, and Hicks must team up with the survivors to destroy the parasites. The film ends with a teaser for a fourth movie, where Bishop suggests to Hicks that humans are united against a common enemy, and they must track the Aliens to their source and destroy them.[18] The screenplay was very action oriented, featuring an extended cast, and is considered in some circles as superior to the final film and has a considerable following on the Internet.[22] The producers were on the whole unsatisfied with the screenplay, which Giler described as "a perfectly executed script that wasn't all that interesting",[17] particularly for not taking new directions with the initial pitch. They still liked certain parts, such as the subtext making the Alien a metaphor for HIV, but felt it lacking the human element present in Aliens and Gibson's trademark cyberpunk aesthetic. Following the end of the WGA strike, Gibson was asked to make rewrites with Harlin, but declined, citing various other commitments and "foot dragging on the producers' part."[18] On July 12, 2018, it was announced that William Gibson's unmade screenplay of Alien 3 will be adapted into a comic series.[23] As part of the Alien's 40th anniversary, on May 30, 2019, the audiobook version of William Gibson's unproduced screenplay of Alien 3 was released and made available on Audible.[24]

Following Gibson's departure, Harlin suggested screenwriter Eric Red, writer of the cult horror films The Hitcher and Near Dark. Red worked less than two months to deliver his draft on February 1989,[18] which led him to later describe his Alien 3 work as "the one script I completely disown because it was not 'my script'. It was the rushed product of too many story conferences and interference with no time to write, and turned out utter crap."[25] His approach had a completely new set of characters and subplots, while also introducing new breeds of the Alien.[18] The plot opened with a team of Special Forces marines boarding the Sulaco and finding that all survivors had fallen victim to the aliens. Afterwards, it moved into a small-town U.S. city in a type of bio-dome in space, culminating in an all-out battle with the townsfolk facing hordes of Alien warriors. Brandywine rejected Red's script for deviating too much from their story, and eventually gave up on developing two sequels simultaneously.[18] Writer David Twohy was next to work on the project, being instructed to start with Gibson's script. Once the fall of Communism made the Cold War analogies outdated, Twohy changed his setting to a prison planet, which was being used for illegal experiments on the aliens for a Biological Warfare division.[18] Harlin felt this approach was too similar to the previous movies, and, tired of the development hell, walked out on the project, which led Fox to offer Harlin The Adventures of Ford Fairlane.[26]

Twohy's script was delivered to Fox president Joe Roth, who did not like the idea of Ripley being removed, declaring that "Sigourney Weaver is the centerpiece of the series" and Ripley was "really the only female warrior we have in our movie mythology."[27] Weaver was then called, with a reported $5 million salary, plus a share of the box office receipts.[19] She also requested the story to be suitably impressive, original and non-dependent on guns. Twohy duly set about writing Ripley into his screenplay.[27]

Start-up with Vincent Ward

Once Hill attended a screening of The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey, he decided to invite its director, Vincent Ward. Ward, who was in London developing Map of the Human Heart,[18] only accepted the project on the third call as he at first was uninterested in doing a sequel. Ward thought little of the Twohy script, and instead worked up another idea, involving Ripley's escape pod crash landing on a monastery-like satellite. Having developed this pitch on his flight to Los Angeles, once Ward got with the studio executives he saw his idea approved by the studio. Ward was hired to direct Alien 3, and writer John Fasano was hired to expand his story into a screenplay.[17] Once Twohy discovered through a journalist friend that another script was being written concurrently with his, he went after Fox and eventually left the project.[28]

Ward envisioned a planet whose interior was both wooden and archaic in design, where Luddite-like monks would take refuge. The story begins with a monk who sees a "star in the East" (Ripley's escape pod) and at first believes this to be a good omen. Upon arrival of Ripley, and with increasing suggestions of the Alien presence, the monk inhabitants believe it to be some sort of religious trial for their misdemeanors, punishable by the creature that haunts them. By having a woman in their monastery, they wonder if their trial is partially caused by sexual temptation, as Ripley is the only woman to be amongst the all-male community in ten years. To avoid this belief and (hopefully) the much grimmer reality of what she has brought with her, the Monks of the "wooden satellite" lock Ripley into a dungeon-like sewer and ignore her advice on the true nature of the beast.[29] The monks believe that the Alien is in fact the Devil. Primarily though, this story was about Ripley's own soul-searching complicated by the seeding of the Alien within her and further hampered by her largely solo attempts to defeat it. Eventually Ripley decides to sacrifice herself to kill the Alien. Fox asked for an alternative ending in which Ripley survived, but Weaver would only agree to the film if Ripley died.[17]

Empire magazine described Ward's 'Wooden Planet' concept as 'undeniably attractive—it would have been visually arresting and at the very least, could have made for some astonishing action sequences.' In the same article, Norman Reynolds—Production Designer originally hired by Ward—remembers an early design idea for "a wooden library shaft. You looked at the books on this wooden platform that went up and down". 'Imagine the kind of vertical jeopardy sequence that could have been staged here—the Alien clambering up these impossibly high bookshelves as desperate monks work the platform'.[27]:156 Sigourney Weaver described Ward's overall concept as "very original and arresting."[27]:153 Former Times journalist David Hughes included Ward's version of Alien 3 amongst "The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made" in his book of this title.[30]

However, the concept was divisive among the production crew. The producers at Brandywine discussed the logical problems of creating and maintaining a wooden planet in space, while Fox executive Jon Landau considered Ward's vision to be "more bent on the artsy-fartsy side than the big commercial one" that Ridley Scott and James Cameron employed. Ward managed to dissuade the producers of their idea of turning the planet into an ore refinery and the monks into prisoners, but eventually Fox asked a meeting with the director imposing a list of changes to be made. Refusing to do so, Ward was fired. The main plot of the finished film still follows Ward's basic structure.[17]

Walter Hill and David Giler's script

Hill and Giler did a first draft trying to enhance the story structure on the Fasano script, and feeling creatively drained hired Larry Ferguson as a script doctor. Ferguson's work was not well received in the production, particularly by Sigourney Weaver, who felt Ferguson made Ripley sound like "a pissed-off gym teacher". Short on time before filming was due to commence, producers Walter Hill and David Giler took control of the screenplay themselves, melding aspects of the Ward/Fasano script with Twohy's earlier prison planet screenplay to create the basis of the final film.[18] Sigourney Weaver had also had a clause written into her contract stating the final draft should be written by Hill and Giler, believing that they were the only writers (besides James Cameron) to write the character of Ripley effectively.[17] Fox approached music video director David Fincher to replace Ward.[31] Fincher did further work on the screenplay with author Rex Pickett, and despite Pickett being fired and Hill and Giler writing the final draft of the screenplay, he revised most of the work done by the previous authors.[32] Fincher wanted Gary Oldman to star in the film, but the pair "couldn't work it out".[33]

Production

Filming

Filming began on January 14, 1991, at Pinewood Studios without a finished script and with $7 million already having been spent.[19] While a majority of the film was shot at Pinewood, some scenes were shot at Blyth Power Station in Northumberland, UK.[34] The purpose of these shots were to show the exterior of the planet.[35] Cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth worked only for two weeks before he started suffering from Parkinson's disease, and was forced out of the film by a line producer who had lost his father to the disease several years previously, and knew that if anything, the demanding schedule would likely take a fatal toll on Cronenweth's health. He was replaced by Alex Thomson.[36] Actor Charles Dance said that an alternative ending had been filmed due to fears that the original ending was too similar to the ending of Terminator 2: Judgment Day, released the previous year, but was not used.[37]

Visual effects

Stan Winston, responsible for creature effects in Aliens, was approached but was not available. Winston instead recommended Tom Woodruff Jr. and Alec Gillis, two former workers of his studio who had just started their own company, Amalgamated Dynamics.[15] Even before principal photography had begun, the practical effects crew was developing models of the Alien and the corpses of the Sulaco victims. Richard Edlund's Boss Film Studios was hired for compositing and other post-production effects.[17] A small number of shots contain computer-generated imagery, most notably the cracking alien head once the sprinklers cause thermal shock. Other CGI elements include shadows cast by the rod puppet alien, and airborne debris in outdoor scenes.[38]

David Fincher wanted the alien to be, "more of a puma, or a beast" as opposed to the upright, humanoid posture of the previous films, so the designer of the original alien, H. R. Giger, was contacted to generate new sketch ideas. His revisions included longer, thinner legs, the removal of "pipes" around the spine, and an idea for a sharp alien "tongue" in place of the secondary jaws. Working from his studio in Zurich, Giger produced these new sketches which he faxed to Cornelius de Fries who then created their model counterparts out of plasticine.[39] The only one of Giger's designs that wound up in the final project was a "Bambi Burster" Alien that had long legs and walked on all fours. ADI also built a full-scale Bunraku-style puppet of this design which was operated on-set as an in-camera effect. Scenes using this approach were cut from the final release due to the limitations of chemical compositing techniques, making it exceedingly difficult to remove the puppeteers from the background plate, but can be seen in the "Assembly Cut" of the film.[40]

The Alien is portrayed by both Woodruff Jr. in a suit and a rod puppet filmed against bluescreen and optically composited into the live-action footage, with the rods removed by rotoscoping. A mechanical alien head was also used for close-ups.[38] The suit adapted the design used in Aliens so Woodruff could walk on all fours.[15] Woodruff's head was contained in the neck of the suit, because the head was filled with animatronics to move the mouth of the Alien.[16] Fincher suggested that a Whippet be dressed in an alien costume for on-set coverage of the quadrupedal alien, but the visual effects team was dissatisfied with the comical result and the idea was dropped in favor of the puppet.[38]

The rod-puppet approach was chosen for the production rather than stop-motion animation which did not provide the required smoothness to appear realistic. As a result, the rod-puppet allowed for a fast alien that could move across surfaces of any orientation and be shot from any angle.[40] This was particularly effective as it was able to accomplish movements not feasible by an actor in a suit. The ⅓-scale puppet was 40 inches long and cast in foam rubber over a bicycle chain armature for flexibility.[41] For moving camera shots, the on-set cameras were equipped with digital recorders to track, pan, tilt, and dolly values. The data output was then taken back to the studio and fed into the motion control cameras with the linear dimensions scaled down to match the puppet.[40]

To make syncing the puppet's actions with the live-action shots easier, the effects team developed an instant compositing system using LaserDisc. This allowed takes to be quickly overlaid on the background plate so the crew could observe whether any spatial adjustments were required.[40]

Laine Liska was hired to lead a team of puppeteers in a new process dubbed "Mo-Motion" where the rod puppet would be simultaneously manipulated and filmed with a moving motion control camera.[40] Depending on the complexity of the shot, the puppet was operated by 4–6 people.[41] Sparse sets were created to provide freedom of motion for the puppeteers as well as large, solid surfaces for the puppet to act within a three dimensional space.[40]

The crew was pushed to make the movements of the Alien as quick as possible to the point where they were barely in control, and this led to, according to Edlund, "the occasional serendipitous action that made the alien have a character." The ease of this setup allowed the crew to film 60–70 takes of a single scene.[40]

Hoping to give the destroyed Bishop a more complex look that could not be accomplished by simple make-up, the final product was done entirely through animatronics, while a playback of Lance Henriksen's voice played to guide Sigourney Weaver.[17]

Scenes of the Emergency Escape Vehicle were shot with a 3.5-foot miniature against a blue-screen and composited onto large scale traditional matte paintings of the planet's surface. To make the clouds glow from within as the EEV entered the atmosphere, the painting's values were digitally reversed and animated frame by frame. The scene in which the EEV is moved by a crane-arm (also a miniature) was created by projecting a video of actors onto pieces of cardboard and then compositing them into the scene as silhouettes against the matte-painted background.[40]

Music

The film's composer, Elliot Goldenthal, spent a year composing the score by working closely with Fincher to create music based primarily on the surroundings and atmosphere of the film itself. The score was recorded during the 1992 Los Angeles riots, which Goldenthal later claimed contributed to the score's disturbing nature.[42]

Reception

Box office

The film was released in the United States on May 22, 1992. The film debuted at number two of the box office, behind Lethal Weapon 3, with a Memorial Day weekend gross of $23.1 million. It screened in 2,227 theaters, for an average gross of $8,733 per theater.[2] The film was considered a flop in North America with a total of $55.5 million, although it grossed $104.3 million internationally[43] for a total of $159.8 million. Based on that figure, it is the second-highest-earning Alien film, excluding the effect of inflation, and had the 28th-highest domestic gross in 1992.[2] In October 1992, Fox claimed it was the highest-grossing of the franchise, with a worldwide gross of $175 million.[5]

Critical reception

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 44% from 55 reviews, with an average rating of 5.34/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Alien 3 takes admirable risks with franchise mythology, but far too few pay off in a thinly scripted sequel whose stylish visuals aren't enough to enliven a lack of genuine thrills."[44] Metacritic assigned a weighted average score of 59 out of 100 based on 20 critics, signifying "mixed or average reviews".[45] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "C" on an A+ to F scale.[46]

In his review of Alien Resurrection, Roger Ebert wrote "I lost interest [in Alien 3], when I realized that the aliens could at all times outrun and outleap the humans, so all the chase scenes were contrivances."[47] Ebert later stated in his review of Fight Club that he considered Alien 3 "one of the best-looking bad movies he's ever seen".[48]

A number of cast and crew associated with the series, including actor Michael Biehn, previous director James Cameron, and novelist Alan Dean Foster, expressed their frustration and disappointment with the film's story. Cameron, in particular, regarded the decision to kill off the characters of Bishop, Newt, and Hicks as a "slap in the face" to him and to fans of the previous film. Upon learning of Hicks' demise, Biehn demanded and received almost as much money for the use of his likeness in one scene as he had been paid for his role in Aliens.[49][50]

David Fincher eventually disowned the film, later stating in an interview with The Guardian in 2009 that "No one hated it more than me; to this day, no one hates it more than me."[51] He also blamed the producers for not putting the necessary trust in him.[52][53][54]

Awards

The film's visual effects were nominated for an Academy Award, losing to Death Becomes Her. The film was also nominated for seven Saturn Awards and an MTV Movie Award for Best Action Sequence.[55]

Adaptations

A novelization of the film was authored by Alan Dean Foster. His adaptation includes many scenes that were cut from the final film, some of which later reappeared in the "Assembly Cut". Foster wanted his adaptation to differ from the film's script, which he disliked, but Walter Hill declared he should not alter the storyline. Foster later commented: "So out went my carefully constructed motivations for all the principal prisoners, my preserving the life of Newt (her killing in the film is an obscenity), and much else. Embittered by this experience, that's why I turned down Alien Resurrection."[56]

Dark Horse Comics also released a three-issue comic book adaptation of the film.[57]

The official licensed video game was developed by Probe Entertainment, and released for multiple formats by Acclaim, LJN and Virgin Games, including Amiga, Commodore 64, Nintendo Entertainment System, Super NES, Mega Drive/Genesis and Master System. Rather than being a faithful adaptation of the film, it took the form of a basic platform action game where the player controlled Ripley using the weapons from the film Aliens in a green-dark ambient environment.[58] The Game Boy version, developed by Bits Studios, was different from the console game, being a top-down adventure game. Sega also developed an arcade rail shooter loosely based on the film's events, Alien 3: The Gun, which was released in 1993.

A cartoon series titled Operation: Aliens was conceived by Fox to coincide with the film's release but was ultimately abandoned. Animation on the pilot episode was carried out by a Korean animation studio. Footage has never surfaced, but still images have leaked online. Some merchandising was also released.[59]

William Gibson's Alien 3

In 2018–19, Dark Horse released William Gibson's Alien 3, a five-part comic adaptation of Gibson's unproduced version of the screenplay, illustrated and adapted by Johnnie Christmas, colored by Tamra Bonvillain.[23]

In 2019, Audible released an audio drama of Gibson's script, adapted by Dirk Maggs and with Michael Biehn and Lance Henriksen reprising their roles.[60] The production had music by James Hannigan.

Home media

Alien 3 has been released in various home video formats and packages over the years. The first of these were on VHS and LaserDisc, and several subsequent VHS releases were sold both singly and as boxed sets throughout the 1990s. A VHS boxed set titled The Alien Trilogy containing Alien 3 along with Alien and Aliens was released in facehugger-shaped carrying cases, and included some of the deleted scenes from the LaserDisc editions. When Alien Resurrection premiered in theaters in 1997, another boxed set of the first three films was released titled The Alien Saga, which included a Making of Alien Resurrection tape. A few months later, this set was re-released with the Alien Resurrection film taking the place of the making-of video. In 1999, Alien 3 was released on DVD, both singly and packaged with the other three Alien films as The Alien Legacy boxed set. This set was also released in a VHS version and would be the last VHS release of the film. In 2003, Alien 3 would be included in the 9-disc Alien Quadrilogy DVD set which contained two versions of the film (see below). The first three films were also later packaged as the Alien Triple Pack DVD set (this release was identical to the 1999 Alien Legacy set but excluding Alien Resurrection). Alien 3 was first released on Blu-ray in 2010, as part of the 6-disc Alien Anthology boxed set which included all of the features from the Alien Quadrilogy DVD set and more. The film was also released as a single Blu-ray Disc in 2011.

The bonus disc for Alien 3 in the 2003 Quadrilogy set includes a documentary of the film's production, that lacks Fincher's participation as clips where the director openly expresses anger and frustration with the studio were cut.[61] The documentary was originally named Wreckage and Rape after one of the tracks of Goldenthal's soundtrack, but Fox renamed it simply The Making of Alien 3. These clips were restored for the 2010 Blu-ray release of the Anthology set, with the integral documentary having a slightly altered version of the intended name, Wreckage and Rage.[62]

Assembly Cut

An alternative version of Alien 3 (officially titled the "Assembly Cut")[63] which included 37 minutes and 12 seconds of new and alternative footage was released on the 9-disc Alien Quadrilogy box set in 2003, and later in the Alien Anthology Blu-ray set in 2010. The film's extended and alternative footage includes alternative key plot elements, extended footage, deleted scenes, and new digital effects.[64] This version is 30 minutes longer than the theatrical release, and Fincher was the only director from the franchise who declined to participate in the box-set releases, even though the Assembly Cut received his blessing.

The "Assembly Cut" has several key plot elements that differ from the theatrical release, and the film has subsequently gained more favorable reviews and something of a cult following, being praised as an avant-garde work of depressive realism in cinema.

Sequel

A sequel, Alien Resurrection, was released in 1997.

References

- "ALIEN 3". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- "Alien 3 (1992)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- "Alien 3 – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- Alien 3 at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "The Baddest of Them All (Fox advertisement)". Daily Variety. October 6, 1992. p. 8.

- Baldwin, Daniel (May 2, 2016). "Exhumed & Exonerated: 'Alien 3' (1992)". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- The Arrow (June 5, 2012). "A Look Back at the Two Cuts of Alien 3 (1992)!". Joblo. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- "Scified". Scified. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "In Defense of Alien 3: Assembly Cut". Audiences Everywhere. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "The Destiny of Ellen Ripley". The Drunken Odyssey. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- The Alien species is defined as "Xenomorph" within the previous film Aliens, and is later referred to as "Xenomorph" by Ripley when she is sending an email to Weyland-Yutani.

- Identified as Michael Bishop Weyland in tie-in materials.

- Hewitt-McManus, Thomas (2006). Withnail & I: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know But Were Too Drunk to Ask. Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Press Incorporated. p. 20. ISBN 978-1411658219.

- Alien3 audio commentary, Alien Quadrilogy boxset

- "Tom Woodruff, Jr. interview". Icons of Fright.com. 2007.

- "Interview: Amalgamated Dynamics' Tom Woodruff, Jr". Shock Till You Drop. April 14, 2008. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- Wreckage and Rage: The Making of Alien 3 (Blu-Ray). Alien Anthology Disk 5: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment. 2010.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Bald Ambition". Cinescape. November 1997. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- "Last in Space". Entertainment Weekly. May 29, 1992. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- "William Gibson talks about the script". WilliamGibsonBooks.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- Luke Savage. "Renny Harlin interview: 12 Rounds, Die Hard, and the Alien 3 that never was". Denofgeek.com. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- Mark H. Harris. "10 of the Greatest Horror Movies Never Made". About.com. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- Staley, Brandon (July 12, 2018). "William Gibson's Unproduced Alien 3 Script to be Adapted by Dark Horse". CBR. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Audible UK | Free Audiobook with 30-Day Trial.

- Clint. "Q&A with Eric Red". Movie Hole. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- Bibbiani, William (August 17, 2011). "Interview: Renny Harlin on '5 Days of War'". Crave. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- Jolin, Dan (December 2008). "Backstory Alien III – Alien: Reinvented". Empire: 150–156.

- Stovall, Ada (September 24, 2013). "Riddick's David Twohy". Creative Screenwriting. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- vincentwardfilms.com, Alien 3 Unrequited Vision, retrieved on 2009:10:30 http://www.vincentwardfilms.com/concepts/alien-3/unrequited-vision/%5B%5D

- Hughes, David (2001). The Greatest Sci-fi Movies Never Made. ISBN 978-1556524493.

- Pearce, Garth (1991). "Alien3: Set Visit To A Troubled Sequel". Empire. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015.

- Richardson, John H. (2014). "Mother from Another Planet". In Knapp, Laurence F. (ed.). David Fincher: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-628460-36-0.

- Rebello, Stephen (September 16, 2014). "Interview: David Fincher". Playboy. Archived from the original on September 17, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- "Structure details". SINE Project (Structural Images of the North East). Newcastle University. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- "Alien 3 Workprint (1992) DVD". WTFDVDs. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- Wreckage and Rape: The Making of Alien 3 – Stasis Interrupted: David Fincher's Vision and The Downward Spiral: Fincher vs. Fox (Alien 3 Collector's Edition DVD)

- Kermode, Mark (June 1992). "Dances with Aliens". Fangoria (113): 36–39 – via Internet Archive.

- Fredrick Garvin (Director) (2003). The Making of Alien 3 (DVD). United States: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment.

- Xeno-Erotic: The H.R. Giger Redesign" (DVD). Alien Quadrilogy (Alien 3) bonus disc: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment. 2003.CS1 maint: location (link)

- David Fincher (Director) (2003). Alien Quadrilogy (Alien 3) bonus disc "Optical Fury" (DVD). United States: Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment.

- "H.R. Giger". Imagi-Movies Magazine. 1 (3). 1994.

- "Music, Editing and Sound"; Alien3 bonus disc, Alien Quadrilogy

- Hochman, David (December 5, 1997). "Beauties and the Beast". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- "Alien3 (1992)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Alien 3 Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- Ebert, Roger (November 26, 1997). "Alien Resurrection Roger Ebert review". Sun Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- Ebert, Roger (October 15, 1999). "Fight Club". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- Wreckage and Rape: The Making of Alien 3 – Development Hell: Concluding The Story (Alien 3 Collector's Edition DVD)

- Kirk, Jeremy (June 14, 2012). "36 Things We Learned From the 'Aliens' Commentary". filmschoolrejects.com. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Salisbury, Mark; Fincher, David (January 18, 2009). "Transcript of the Guardian interview with David Fincher at BFI Southbank". The Guardian. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Director's Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century. ASIN 082641902X.CS1 maint: ASIN uses ISBN (link)

- Suderman, Peter (May 22, 2017). "Alien 3 is far from the worst Alien movie. In fact, it's pretty great". Vox. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Spry, Jeff (May 22, 2017). "Embracing the Grime and Grandeur of ALIEN 3 on its 25th Anniversary". SyfyWire. SYFY. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- "1993 MTV Movie Awards". mtv.com. MTV. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- Alan Dean Foster (April 2008). "Planet Error". Empire. p. 100.

- Steven Grant (w). Alien 3 1–3 (June – July 1992), Dark Horse Comics

- "Alien 3 for Amiga (1992) – MobyGames". MobyGames. July 9, 2005. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- "The Failed 'Aliens' Cartoon and the Kenner Toys it Inspired". ComicsAlliance. April 26, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- Alien III Teaser

- "Criticism of Bonus Disc". The Digital Bits. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Latchem, John (July 22, 2010). "Blu-ray Producers: Extras Are for the Fans, By Fans". Home Media Magazine. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "DVD Verdict". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "DVD Verdict Review – Alien3: Collector's Edition". Archived from the original on June 13, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

Further reading

- Gallardo C., Ximena; and C. Jason Smith (2004). Alien Woman: The Making of Lt. Ellen Ripley. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1569-5

- Murphy, Kathleen. "The Last Temptation of Sigourney Weaver." Film Comment 28. 4 (July–August 1992): 17-20.

- Speed, Louise. "Alien3: A Postmodern Encounter with the Abject." Arizona Quarterly 54.1 (Spring 1998): 125-51.

- Syonan-Teo, Kobayashi. "Why Sigourney is Jesus: Watching Alien3 [sic] in the Light of Se7ven." The Flyng Inkpot. 1998.

- Taubin, Amy. "Invading Bodies: Aliens3 [sic] and the Trilogy." Sight and Sound (July -August 1992): 8-10. Reprinted as "The 'Alien' Trilogy: From Feminism to AIDS." Women and Film: A Sight and Sound Reader. Ed. Pam Cook and Philip Dodd. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993. 93-100.

- Thomson, David. "The Bitch is Back." Esquire. December 1997: 56-7.

- Vaughn, Thomas. "Voices of Sexual Distortion: Rape, Birth, and Self-Annihilation Metaphors in the Alien Trilogy." The Quarterly Journal of Speech 81. 4 (November 1995): 423-35.

- Williams, Anne. "Inner and Outer Spaces: The Alien Trilogy." Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alien 3. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alien 3 |

- Alien 3 on IMDb

- Alien 3 at Rotten Tomatoes

- Alien 3 at AllMovie

- Alien 3 at Box Office Mojo

- Alien 3 at the American Film Institute Catalog