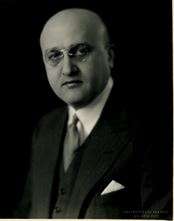

Albert M. Greenfield

Albert Monroe Greenfield (August 4, 1887 – January 5, 1967)[1] was a real estate broker and developer who built his company into a vast East Coast network of department stores, banks, finance companies, hotels, newspapers, transportation companies and the Loft Candy Corporation. His high-rise office buildings and hotels were instrumental in changing the face of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, his base of operations. Uniquely for his time, he formed business relationships across religious, ethnic and social lines and played a major role in reforming politics in Philadelphia as well as at the national level.[2]

Albert Monroe Greenfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Avrum Moishe Grunfeld August 4, 1887 |

| Died | January 5, 1967 (aged 79) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Occupation | Real estate broker and developer, banker, investor, board director, trustee, philanthropist |

| Official name | Albert M. Greenfield (1887-1967) |

| Type | City |

| Criteria | African American, Business & Industry, Government & Politics 20th Century, Religion |

| Designated | April 21, 2016 |

| Location | 1315 Walnut St., Philadelphia 39.94931°N 75.16294°W |

Early life and business activities

Greenfield was born Avrum Moishe Grunfeld to a Jewish family[3] in 1887 to trader Jacob Gruenfeld and wife Esther (née Serody) in Lozovata, a village in what is now south-central Ukraine. After emigrating to New York City in 1892, he and his family (with names anglicized) moved in 1896 to Philadelphia, settling in South Philadelphia where Jacob Greenfield ironed shirts in a factory and operated a grocery in the family's home.[4] Albert left high school at age 14 to become a clerk for a prominent local real estate lawyer.[5] In this position, Greenfield found his calling as a real estate broker.[6]

In May 1905, Greenfield opened his own real estate firm at 218 South 4th Street, with $500 that his mother borrowed for him from her brother.[7] Within seven years Greenfield was earning $60,000 a year; by 1917, his personal wealth had increased to $15 million.[8] During the 1920s he largely rebuilt the face of downtown Philadelphia, creating numerous landmark office buildings and hotels, including what was then the world's largest hotel, the Benjamin Franklin, in 1925.[9]

The alliances created through his growing real estate business led to investments in motion picture theaters, building and loan associations, and mortgage financing. By the early 1920s he controlled 27 building and loan associations. In 1924, Greenfield and his father-in-law Sol C. Kraus formed Bankers Bond & Mortgage Company to handle first mortgages on real estate in Philadelphia. After expanding to the New York City market, the firm was renamed Bankers Bond & Mortgage Company of America. By 1930 his real estate concern, known as Albert M. Greenfield & Co. since 1911, was the largest real estate company in the U.S.[10] and Greenfield sought to become a commercial banker.

In late 1926 he bought a controlling interest in a small West Philadelphia bank and, through a series of acquisitions, built it over the next four years into Bankers Trust Company, Philadelphia's tenth largest bank, with $50 million in deposits.[11] In May 1928, Greenfield formed the Bankers Securities Corporation (BSC) for general investment banking and trading in securities, which eventually became the parent company for virtually all of Greenfield's financial interests. But a run on his bank forced the closing of Bankers Trust on December 22, 1930, and ended Greenfield's career as a banker, leaving him millions in debt. But in the depth of the Great Depression, he refused to seek bankruptcy protection and instead reinvented himself as a retailing magnate, gaining control of the insolvent City Stores Company, a chain that operated seven department stores in six states. The company expanded throughout the East Coast over the next 20 years.[12] When asked much later about his negative experiences during the Depression, Greenfield replied, "It wasn't too bad. I've always treated both success and failure as imposters. I like making money, but I can get along without it. I never worried about having it because I knew I could always make more."[1]

Politics

In 1917, Greenfield was elected to a seat on the Philadelphia Common Council and served until 1920. Originally a Republican, he switched parties with the advent of the New Deal in 1933 and remained a strong Democratic supporter until his death. He enjoyed a close relationship with many Presidents from Herbert Hoover to Lyndon Johnson. In 1951 he played a major role in the defeat of Philadelphia's long-entrenched Republican machine. As chairman of Philadelphia's City Planning Commission under Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1956–58), he laid the foundation for the development of Society Hill as a unique upper-middle-class enclave capable of luring suburbanites back to downtown.[13] Because of his political activism, in 1948 Philadelphia hosted both the Republican and the Democratic party conventions.

Board memberships

Greenfield's reputation for producing results placed him in high demand. He was involved or interested in almost everything, becoming known in his time as "Mr. Philadelphia".[14] At one point in the 1940s, he sat on 43 boards. A few significant ones included the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company and successor Philadelphia Transportation Company (predecessors of SEPTA), Girard College, the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, the Urban Land Institute, the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the American Jewish Tercentenary Committee, the Sesquicentennial Exposition, Albert Einstein Medical Center, and the Federation of Jewish Charities.

Philanthropy and legacy

In the early 1950s, Greenfield donated $1 million to the University of Pennsylvania for creation of the Albert M. Greenfield Center for Human Relations, the nation's first institution specifically designed to train students to promote interfaith and interracial relations.[15]

In 1953, he established The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation to provide grants to a variety of local Philadelphia institutions. The Foundation has supported the Albert Monroe Greenfield Memorial Lecture in Human Relations, an annual event at the University of Pennsylvania held under the terms of the endowment of the Greenfield Professorship of Human Relations. The professorship was established in 1972.[16] In 1992, the Foundation endowed The Albert M. Greenfield Student Competition, The Philadelphia Orchestra, to recognize extraordinary young musical talent in the Greater Delaware Valley region.[17] The Foundation has also funded the Albert M. Greenfield Digital Imaging Center at The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia,[18] the Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia,[19] and the digital and print Albert M. Greenfield Center for 20th-Century History at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.[20]

Since 1984, the University of Pennsylvania has also hosted the Albert M. Greenfield Intercultural Center. Its original mission was "to provide support for student of color and to foster intercultural understanding on campus". Over the years the center has maintained this mission while expanding its programs.[21]

His philanthropic endeavors transcended religious and racial lines. He was praised for his work by such organizations as the National Conference of Christians and Jews, the World Brotherhood Organization, the Urban League, and the Catholic Interracial Council. For his philanthropic work, he was bestowed with the rank of Commander of the Order of Pius IX by Pope Pius XI.[1] He was the first Jew in America to receive such an honor. In 2016, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission placed a marker honoring Greenfield near the corner of Walnut and Juniper Streets in Center City. The marker notes that Greenfield "supported equality for African Americans and received a papal award for promoting Catholic/Jewish harmony."

The Albert M. Greenfield Library is one of two libraries at The University of the Arts, on Broad Street in Center City Philadelphia.

The Albert M. Greenfield Elementary School (part of the School District of Philadelphia), located at 22nd and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, is named in his honor.

Greenfield died on January 5, 1967, at his estate, "Sugar Loaf", in Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. He was survived by his third wife, the former Elizabeth Hallstrom, as well as five children (two sons and three daughters) from his first marriage, 21 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.[22] The Sugar Loaf estate remained in the hands of the Greenfield Foundation as its headquarters, and as the Albert M. Greenfield Conference Center of Temple University, until 2006 when the entire property was sold for $11 million to Chestnut Hill College.[23][24]

References

- "Albert M. Greenfield, Financier, Is Dead at 79". Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. January 5, 1967.

- Dan Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. xi-xiii.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 13

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 17-21.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, 21-24.

- "A Philadelphia Legend". The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 27.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p.28.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 53.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p.28, 35.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 4

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 155-163.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 235-248.

- "Mr. Philadelphia". The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Rottenberg, The Outsider, p. 212.

- University of Pennsylvania, Jerry Lee Center of Criminology website (accessed Sep 1, 2008) Archived September 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- "Philadelphia Orchestra Albert M. Greenfield Student Competition". Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Grant Highlights: The Academy of Natural Sciences Albert M. Greenfield Digital Imaging Center". The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Grant Highlights: Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment". The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Albert M. Greenfield Center for 20th-Century History". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- University of Pennsylvania. "Albert M. Greenfield Intercultural Center". Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- "Albert M. Greenfield Dies at 79; Built Realty and Store Empire". New York Times. January 6, 1967.

- "Chestnut Hill College buying Sugar Loaf," Philadelphia Business Journal, Apr 14, 2006 (accessed Sep 1, 2008)

- "SugarLoaf Hill". Chestnut Hill College. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Finding Aid to the Albert M. Greenfield Papers, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Collection 1959 (accessed August 29, 2008).

- Baltzell, E. Digby (1989) Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class, (Transaction Publishers) ISBN 978-0-88738-789-0.

- Rottenberg, Dan (2014), The Outsider: Albert M. Greenfield and the Fall of the Protestant Establishment (Temple University Press) ISBN 978-1-4399-0841-9.

External links

- Albert M. Greenfield & Co., Inc.

- The Albert M. Greenfield Foundation

- The Albert M. Greenfield Papers, including correspondence, news clippings and office files, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.