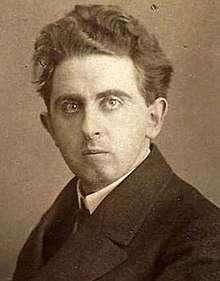

Albert Ehrenstein

Albert Ehrenstein (23 December 1886 – 8 April 1950) was an Austrian-born German Expressionist poet. His poetry exemplifies rejection of bourgeois values and fascination with the Orient, particularly with China.

He spent most of his life in Berlin, but also travelled widely across Europe, Africa, and the Far East. In 1930, he travelled to Palestine, and published his impressions in a series of articles. Shortly before the Nazi take-over, Ehrenstein moved to Switzerland, and in 1941 to New York City, where he died.

Early life

Ehrenstein was born to Jewish-Hungarian parents in Ottakring, Vienna. His father was a cashier at a brewery and the family was poor. His younger brother was the poet Carl Ehrenstein (1892-1971). His mother was able to enroll him in high school, where he was harassed with anti-semitic bullying. From 1905 to 1910 he studied history and philosophy in Vienna and graduated in 1910 with a doctorate (with a thesis on Hungary in 1790). He had already decided on a career of literature, which he described as: "Hardly university studies; but by five years of alleged studies, I secured liberty: Time to do poetic work. Through tolerant overhearing directed to me by mail and offended about to light I put on even a doctorate."

Poetry and writing

In 1910 he wrote the poem "Wanderers song" published by Karl Kraus in the Overnight Torch. The poem is attributed to the early expressionism and was published in 1911 with illustrations by his friend Oskar Kokoschka. Through Kokoschka he came into contact with Herwarth Walden and got it published in Der Sturm, and later in Franz Pfemfert's magazine Die Aktion. Ehrenstein quickly became one of the most important voices of expressionism and came into close contact with Else Lasker-Schüler, Gottfried Benn and Franz Werfel. It was widely circulated Anton Kuh Spottvers wrote about it: "its a high honor of a work, only its verses disturb you."[1]

At the beginning of the First World War, Ehrenstein, who was deemed not fit for military service, was ordered to work in the Vienna War Archives. While many other artists were initially carried away by enthusiasm for the war, Ehrenstein from the beginning was a staunch opponent of the war, which he articulated clearly in a series of articles and poems (The man screams). During the war he came in contact with Walter Hasenclever and Martin Buber. From 1916-17 he belonged to the circle of the first Dadaist magazine The New Youth, in which he published work alongside Franz Jung, George Grosz and Johannes R. Becher. The magazine took a clearly anti-Wilhelm position and was quickly banned. Becher and Ehrenstein worked at the same time as editors in publishing Kurt Wolff. After 1918 he supported the revolution in Germany and signed, along with several others including Franz Pfemfert and Zuckmayer, the manifesto of the Antinational Socialist Party.[2]

During the war Ehrenstein met the actress Elisabeth Bergner and helped with her career breakthrough. He fell hopelessly in love with her and dedicated many of his poems to her. In the 1920s he traveled with Kokoschka through Europe, Africa, the Middle East and China, where he remained for a time. He turned to Chinese literature and wrote numerous adaptations from Chinese works and the quite successful novel Murderer from Justice (1931). By the end of 1932 Ehrenstein went to Switzerland to Brissago.

Fugitive on the run

Along with many other authors he was placed on a black list by the Nazi party. In the book burning of 10 May 1933 his books were thrown on the pyre. In the next few years, he published in exile in several journals of literature. In 1934 he travelled to the Soviet Union, and in 1935 went to Paris to attend the "Congress for the Defense of Culture". In Switzerland he was threatened as a foreigner with deportation to Germany. Hermann Hesse tried to help him to get permanent asylum for Ehrenstein but only managed to get him temporary Residence Papers. He prevented extradition by getting Czechoslovak citizenship. He went to England to his brother Carl, then to France, until he was finally able to leave the country for Spain and then to the United States in 1941.

Later life and death

In New York he met with other exiles, including Thomas Mann, Richard Huelsenbeck, and George Grosz, and was granted a residence permit. Ehrenstein learned English, but found no work and lived on the income of articles he wrote for the newspaper, and by loans from George Grosz. In 1949, he returned to Switzerland, then returned to Germany, but was never published and finally returned, disappointed, to New York. After two years he was placed in a pauper's hospice on Welfare, where he died on 8 April 1950. After his death, friends gathered money so his urn could be shipped to England, where his brother Carl was still living. An honorary urn was finally buried in the Bromley Hill Cemetery in London.

Legacy

Ehrenstein's legacy was documented years later at the National Library of Israel, where he was also later re-interred. In his life he influenced many 20th century authors and had personal relationships with many.[3]

Selected works

Poetry and essays

- Tubutsch, 1911 (veränderte Ausgabe 1914, häufige Neuaufl.)

- Der Selbstmord eines Katers, 1912 [4]

- Die weiße Zeit, 1914 [5]

- Der Mensch schreit, 1916

- Nicht da nicht dort, 1916 [6]

- Die rote Zeit, 1917

- Den ermordeten Brüdern, 1919

- Karl Kraus 1920

- Die Nacht wird. Gedichte und Erzählungen, 1920 (Sammlung alter Arbeiten)

- Der ewige Olymp. Novellen und Gedichte, 1921 (Sammlung alter Arbeiten)

- Wien, 1921

- Die Heimkehr des Falken, 1921 (Sammlung alter Arbeiten)

- Briefe an Gott. Gedichte in Prosa, 1922

- Herbst, 1923

- Menschen und Affen, 1926 (Sammlung essayistischer Werke)

- Ritter des Todes. Die Erzählungen von 1900 bis 1919, 1926

- Mein Lied. Gedichte 1900–1931, 1931

- Gedichte und Prosa. Hg. Karl Otten. Neuwied, Luchterhand 1961

- Ausgewählte Aufsätze. Hg. von M. Y. Ben-gavriêl. Heidelberg, L. Schneider 1961

- Todrot. Eine Auswahl an Gedichten. Berlin, hochroth Verlag 2009

Translations and adaptations

- Schi-King. Nachdichtungen chinesischer Lyrik, 1922

- Pe-Lo-Thien. Nachdichtungen chinesischer Lyrik, 1923

- China klagt. Nachdichtungen revolutionärer chinesischer Lyrik aus drei Jahrtausenden 1924; Neuauflage AutorenEdition, München 1981 ISBN 3761081111

- Lukian, 1925

- Räuber und Soldaten. Roman frei nach dem Chinesischen, 1927; Neuaufl. 1963

- Mörder aus Gerechtigkeit, 1931

- Das gelbe Lied. Nachdichtungen chinesischer Lyrik, 1933

Literature

- Fritz Martini (1959), "Ehrenstein, Albert", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 355–355; (full text online)

- A. Ehrenstein. Lesung im Rahmen der Wiener Festwochen 1993 Hg. Werner Herbst & Gerhard Jaschke. (Reihe: Vergessene Autoren der Moderne 67) Universitätsverlag Siegen, 1996 ISSN 0177-9869 [7]

- Stefan Zweig: Albert Ehrensteins Gedichte, in: Rezensionen 1902–1939. Begegnungen mit Büchern. 1983 (E-Text)

Notes

- Ehrenstein, Albert, article in Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Beigel, A. Erlebnis und Flucht im Werk Albert Ehrensteins (1966).

References

- Neuauflage der 12 s/w Bilder in Armin Wallas: A. E.: Mythenzerstörer und Mythenschöpfer, Boer, Grafrath 1994, mit ausführl. Interpretation Wallas'

- Johannes R. Becher: Tagebuchnotiz vom 2. Mai 1950. In: Adolf Endler, Tarzan am Prenzlauer Berg. Sudelblätter 1981–1993. Leipzig: Leipzig, 1994. S. 178 f.

- Würdigung Albert Ehrensteins zu seinem 125. Geburtstag und Kurzbeschreibung des Nachlasses in der National Library of Israel

- Neufassung unter dem Titel Bericht aus einem Tollhaus, 1919

- erst 1916 ausgeliefert

- Neufassung unter dem Titel Zaubermärchen, 1919

- 37 Seiten, dabei 2 S. aus der „Neue Deutschen Biographie“ - Viele kurze Texte quer durch sein Werk, keine Quellenangaben, eine Art Collage