Alamanno da Costa

Alamanno da Costa (active 1193–1224, died before 1229) was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstanding conflict with Pisa and in the origin of its conflict with Venice. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz called him a "famous prince of pirates".[1]

Early free-lance career

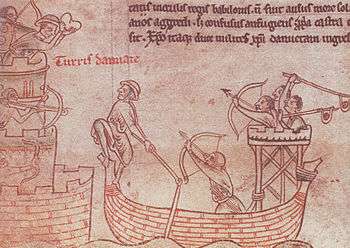

Alamanno came from Genoa's mercantile class, and the earliest record of him dates from 1193, when he joined an accomende, a commercial partnership, directed towards Sicily.[2] In 1204, Alamanno and his son Benvenuto, on their own initiative, set out aboard the Carroccia in search of the Pisan corsair Leopardo.[2] The Carroccia and Leopardo were both classed as navi—broad-beamed, lateen-rigged ships.[3] The former had on board 500 armed men, and the latter probably half as many. The inventory taken after Alamanno successfully captured the Leopardo and integrated her into his force lists 280 suits of armour among the booty. Presumably this represents the number of marines she carried.[4]

In 1162 the Emperor Frederick I signed a treaty with the Republic of Genoa, offering it the city of Syracuse with its countryside as far as Noto if they would provide naval assistance against the Kingdom of Sicily. In 1194, his son, the Emperor Henry VI, confirmed the treaty and with Genoese help took Syracuse in his conquest of Sicily. He refused to honour the treaty and, because they supported the vicar of Sicily, Markward von Anweiler, in 1202 the Pisans, under Count Ranieri di Manenta, took possession of it.[5] It was not until 1204, seven years after Henry's death, that Genoa took possession of the city.[6] Leading a Genoese fleet towards Crete, Alamanno changed course at Malta and, in agreement with Enrico Pescatore, attacked Syracuse, which had only recently been occupied by Pisa.[7] On 6 August, after a six-day siege, during which Alamanno destroyed two Pisan ships, the city fell.[2] Alamanno was acclaimed count in the name of Genoa.[2]

Count of Syracuse

Alamanno took the pompous and probably self-appointed title "by the grace of God, the king and the commune of Genoa, Count of Syracuse [comes Siracuse] and familiaris of the lord king".[1][6] As historian David Abulafia asserts, "it [is] hard to understand what say the Genoese had in the appointment of the counts of a foreign kingdom", yet during the minority of the Sicilian king Frederick I they seem to have had a say.[8] During his tenure, Sicily fell under Genoese hegemony, acting as a trading post, waystation and granary for the republic.[2] It also became a centre of piracy. Alamanno's claim on Syracuse was not recognised by King Frederick I, who was also the Emperor Frederick II.[1] He was thus excluded from the treaty between Genoa and Marseille in 1208, which excluded all "corsairs who reside in or work out of Sicily" (cursales qui in Siciliam morantur vel consuetudinem).[1]

Alamanno was in a close alliance with Enrico Pescatore, to whom he lent the use of the Leopardo.[9] They raided the eastern Mediterranean as far as the County of Tripoli; and both hosted the trobador Peire Vidal, who repaid them with lavish praise.[6] In 1205, off the coast of Provence, three Pisan navi captured a Genoese nave, the Viola, on its way to al-Bijāya. The captured ship was taken to Cagliari and thence to Messina. There it joined a combined Pisan force of navi and twelve galleys and landed a party to attack a Genoese force in the area.[10] The sources are unclear if there were four navi or ten. Two of the galleys were dispatched to Palermo, where they were intercepted and captured by a force of galleys under Alamanno, one of whose ships was commanded by his son.[10] Shortly after, a Pisan fleet of ten navi and twelve galleys (with "many other vessels") and an army under Count Ranieri di Manenta besieged Syracuse for three-and-a-half months. In December 1205, a combined force under Alamanno—who had been leading the defence of the city—and Enrico lifted the siege.[2] Enrico had been at Messina gathering a relief force. Originally it comprised four galleys, some taride (horse transports) and two Genoese navi that were returning from Outremer. The Genoese convinced him to augment this force with more galleys and smaller vessels, as well as sixteen more navi, apparently the most powerful ship class, before attacking the Pisan fleet at Syracuse. The latter contained some nine navi, twelve galleys and fourteen other ships the chronicler refers to merely as buciisque et barchis (bucios and barche).[10]

Activities in the East

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer Byzantine Crete, to which Venice made claim.[6][5] In June 1217, he was captured by the Venetians under Marco Zorzano and imprisoned in an iron cage.[2][1] In 1218 Enrico renounced any claim he had on Crete in favour of Venice and Alamanno was released.[6] In 1219, Alamanno led one galley in support of the Fifth Crusade, and was present at the fall of Damietta.[2]

In 1220 Frederick II began asserting royal rights in Syracuse, attempting to throw out the Genoese, and proclaiming the city "most faithful" (fidelissima).[6] The emperor expropriated the warehouses and other properties belonging to Genoa.[11] After he was expelled from the city in 1221, Alamanno went to Terracina, where Pope Honorius III recommended him to the consuls of the city. In February 1224, Honorius took Alamanno, his family and his possessions under his protection while he was away on crusade. He had agreed to assist the margrave William VI of Montferrat in the reconquest of the Kingdom of Thessalonica in exchange for "one hundred knights or knight's fees" (centum militias seu militaria feuda) or one thousand marks of silver, guaranteed by Honorius.[2] He probably died during the expedition. He was certainly deceased by 1229, when the podestà of Genoa, Iacopo di Balduino, wrote to the judge of Logudoro, Marianus II, ordering him not to give assistance to Caroccino, the illegitimate son of Alamanno, accused of "acts of piracy after the fashion of his father" (exercere pyraticam more patris).[2]

Notes

- Cheyette 1970, p. 46.

- Oreste 1960.

- Dotson 2006, p. 65. The Italian term nave derives from the Latin navis, which also gives rise to the French nef. It was a general term meaning "ship", but modern historians use it in a more technical sense.

- Dotson 2006, p. 66. The primary source is the continuation of the Annales ianuenses by Ogerio Pane.

- Pryor 1999, p. 424. Enrico first began trying to conquer Crete in 1205, when he embarked on a campaign in the eastern Mediterranean, in which he first utilised the Leopardo.

- Abulafia 2004, pp. 1064–65.

- Dotson 2006, p. 68. These Pisans were described as pirati by Ogerio, but the word was a mere pejorative, although the Pisans did prey on Genoese shipping.

- Abulafia 1988, p. 103.

- Dotson 2006, p. 67.

- Dotson 2006, p. 68–69.

- Abulafia 1988, p. 142.

Sources

- Abulafia, David (1988). Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abulafia, David (2004). "Syracuse". In Christopher Kleinheinz (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 1064–65.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cheyette, Fredric L. (1970). "The Sovereign and the Pirates, 1332". Speculum. 45 (1): 40–68. doi:10.2307/2855984. JSTOR 2855984.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dotson, John E. (2006). "Ship Types and Fleet Composition at Genoa and Venice in the Early Thirteenth Century". In John H. Pryor (ed.). Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 63–76.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oreste, Giuseppe (1960). "Alamanno da Costa". In Alberto Maria Ghisalberti (ed.). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. 1. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia italiana. Retrieved 25 April 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pryor, John H. (1999). "The Maritime Republics". In David Abulafia (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 419–46.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)