Al-Musta'sim

Al-Musta'sim Billah (full name: al-Musta'sim-Billah Abu-Ahmad Abdullah bin al-Mustansir-Billah; Arabic: المستعصم بالله أبو أحمد عبد الله بن المستنصر بالله; 1213 – February 20, 1258) was the 37th and last caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate; he ruled from 1242 until his death in 1258.

| Al-Musta'sim Billah المستعصم باللّٰہ | |

|---|---|

| Khalīfah Amir al-Mu'minin | |

Dinar coined under Al-Musta'sim's rule. | |

| Last Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad | |

| Reign | 5 December 1242 – 20 February 1258 (15 years 2 months 15 days) |

| Predecessor | al-Mustansir Billah |

| Successor | Ahmad al-Mustansir as Caliph of Cairo |

| Born | 1213 Baghdad |

| Died | 20 February 1258 (aged 45) |

| Consort | Qurrat al-Ayn, Bab Bachir[1] |

| Dynasty | Abbasid |

| Father | al-Mustansir Billah |

| Mother | Hajir [2] |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Biography

Al-Musta'sim succeeded his father in late 1242.

He is noted for his opposition to the rise of Shajar al-Durr to the Egyptian throne during the Seventh Crusade. He sent a message from Baghdad to the Mamluks in Egypt that said: "If you do not have men there tell us so we can send you men."[3] However, Al-Musta'sim had to face the greatest menace against the caliphate since its establishment in 632: the invasion of the Mongol forces that, under Hulagu Khan, had already wiped out any resistance in Transoxiana and Khorasan. In 1255/1256 Hulagu forced the Abbasid to lend their forces for the campaign against Alamut.

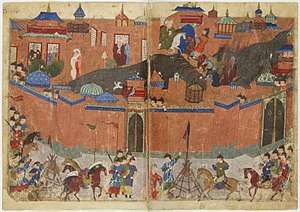

In 1258, Hulagu invaded the Abbasid domain, which then consisted of only Baghdad, its immediate surroundings, and southern Iraq. In his campaign to conquer Baghdad, Hulagu Khan had several columns advance simultaneously on the city, and laid siege to it. The Mongols kept the people of Abbasid Caliphate in their capital and executed those who tried to flee.

Baghdad was sacked on February 10 and the caliph was killed by Hulagu Khan soon afterward. It is reckoned that the Mongols did not want to shed "royal blood", so they wrapped him in a rug and trampled him to death with their horses. Some of his sons were massacred as well; one of the surviving sons was sent as a prisoner to Mongolia, where Mongolian historians report he married and fathered children, but played no role in Islam thereafter.

The Travels of Marco Polo reports that upon finding the caliph's great stores of treasure which could have been spent on the defense of his realm, Hulagu Khan locked him in his treasure room without food or water, telling him "eat of thy treasure as much as thou wilt, since thou art so fond of it."[4][5]

Fall of Abbasids

Hulagu sent word to Al-Musta'sim, demanding his acquiescence to the terms imposed by Möngke. Al-Musta'sim refused, in large part due to the influence of his advisor and grand vizier, Ibn al-Alkami. Historians have ascribed various motives to al-Alkami's opposition to submission, including treachery[6] and incompetence,[7] and it appears that he lied to the Caliph about the severity of the invasion, assuring Al-Musta'sim that, if the capital of the Caliphate was endangered by a Mongol army, the Islamic world would rush to its aid.[7]

Although he replied to Hulagu's demands in a manner that the Mongol commander found menacing and offensive enough to break off further negotiation,[8] Al-Musta'sim neglected to summon armies to reinforce the troops at his disposal in Baghdad. Nor did he strengthen the city's walls. By January 11 the Mongols were close to the city,[7] establishing themselves on both banks of the Tigris River so as to form a pincer around the city. Al-Musta'sim finally decided to do battle with them and sent out a force of 20,000 cavalry to attack the Mongols. The cavalry were decisively defeated by the Mongols, whose sappers breached dikes along the Tigris River and flooded the ground behind the Abbasid forces, trapping them.[7]

Siege of Baghdad

The Abbasid Caliphate could supposedly call upon 50,000 soldiers for the defense of their capital, including the 20,000 cavalry under al-Musta'sim. However, these troops were assembled hastily, making them poorly equipped and disciplined. Although the Caliph technically had the authority to summon soldiers from other Sultanates (Caliphate's deputy states) to defence, he neglected to do so. His taunting opposition had lost him the loyalty of the Mamluks, and the Syrian emirs, who he supported, were busy preparing their own defenses.[9]

On January 29, the Mongol army began its siege of Baghdad, constructing a palisade and a ditch around the city. Employing siege engines and catapults, the Mongols attempted to breach the city's walls, and, by February 5, had seized a significant portion of the defenses. Realizing that his forces had little chance of retaking the walls, Al-Musta'sim attempted to open negotiations with Hulagu, who rebuffed the Caliph. Around 3,000 of Baghdad's notables also tried to negotiate with Hulagu but were murdered.[10] Five days later, on February 10, the city surrendered, but the Mongols did not enter the city until the 13th, beginning a week of massacre and destruction.

Abbasid Dynasty of Cairo

The Mamluk Sultans of Egypt and Syria later appointed an Abbasid Prince as Caliph of Cairo, but these Mamluk Abbasid Caliphs were marginalized and merely symbolic Caliphs, with no temporal power and little religious influence. Even though they kept the title for about 250 years more, other than installing the Sultan in ceremonies, these Caliphs had little importance. After the Ottomans conquered Egypt in 1517, the Caliph of Cairo, Al-Mutawakkil III was transported to Constantinople.

Centuries later, a tradition developed saying that at this time Al-Mutawakkil III formally surrendered the title of caliph as well as its outward emblems—the sword and mantle of Muhammad—to the Ottoman sultan Selim I, establishing the Ottoman sultans as the new caliphal line. Some historians have noted that this story does not appear in the literature until the 1780s, suggesting that it was advanced to bolster the claims of caliphal jurisdiction over Muslims outside of the empire, as asserted in the 1774 Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca.[11]

See also

- Sulaiman Shah Governor of Kurdistan and an Abbasid officer.

- Yaqut al-Musta'simi a well-known calligrapher and secretary of the last abbasid caliph Al-Musta'sim.

- Siege of Baghdad (1258)

- Mongol invasions of the Levant

- Berke Muslim Mongolian ruler.

- Berke–Hulagu war

- Tekuder son of Hulagu and a Muslim Convert.

References

- Al-Hawadith al-Jami'a . Ibn al-Fuwaṭi

- Al-Hawadith al-Jami'a . Ibn al-Fuwaṭi

- Al-Maqrizi, p.464/vol1

- Yule-Cordier Edition

- Ibn al-Furat; translated by le Strange, 1900, pp. 293–300

- Zaydān, Jirjī (1907). History of Islamic Civilization, Vol. 4. Hertford: Stephen Austin and Sons, Ltd. p. 292. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- Davis, Paul K. (2001). Besieged: 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 67.

- Nicolle

- James Chambers, "The Devil's Horsemen," p. 144.

- Fattah, Hala. A Brief History of Iraq. Checkmark Books. p. 101.

- Lewis, Bernard (1961). The Emergence of Modern Turkey. Oxford University Press.

Sources

- Al-Maqrizi, Al Selouk Leme'refatt Dewall al-Melouk, Dar al-kotob, 1997.

- Ibn al-Furat; le Strange (1900). "The Death of the Last Abbasid Caliph, from the Vatican MS. of Ibn al-Furat". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 32: 293–300.

Al-Musta'sim Abbasid dynasty Cadet branch of the Banu Hashim Born: 1213 Died: 20 February 1258 | ||

| Sunni Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Al-Mustansir |

Last Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate Caliph of Islam Abbasid Caliph 5 December 1242 – 20 February 1258 |

Vacant Title next held by Al-Mustansir |