Ahwahnechee

The Ahwahnechee or Awahnichi (″People of The Mouth″) are a Miwok people who traditionally lived in the Yosemite Valley, which they called Ahwahnee. They were known to their Northern Paiute cousins as Wea Dukadu ("Acorn Eaters").[1] The Ahwahnechee people's heritage can be found all over Yosemite National Park.[2][3]

History

Traces of human habitation in the valley go back to as long about 3,000 years. Mariposa Phase settlements, which show archaeological continuity with the historical Ahwahnechee, appear from about 800 years ago.[4]

Early Settler Colonialism

Presence of the Ahwahnechee was first recorded by white people in the context of the California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century. In 1850 a settler named James D. Savage set up a mining camp down below the valley, and spent most of his time mining for gold and trading with the few other white men in the area. He stole several Indian women and took them as "wives" and developed influential relations with the nearby natives. After taken indigenous women, later that year, Savage's camp and post were attacked by the Ahwahnechee, who raided his supplies, and killed two of his men in a likely attempt to free their community members. This, in turn, sparked the Mariposa Indian War of 1850 to 1851. In 1851, during the Mariposa War, California State Militia troops of the Mariposa Battalion burned Ahwahnechee villages and took their food stores in an act of war and genocide.[5]

The state militia with Savage as their major and the Indian Commissioners from Washington were called out to either force the natives to sign treaties. Six tribes made agreements with the government to accept reservation land further down into the foothills. One of the tribes that refused to meet was the Ahwahnechees. When the soldiers, led by Savage, moved towards their camp to force them out, their chief, Teneiya, finally appeared alone and attempted to conceal the location and number of his people. Major Savage told Teneiya that he would travel to the valley to find them. Chief Teneiya said that he would go back and return with his tribe. When the chief appeared again Savage noticed that there were very few of the natives present. He asked the chief where the rest of his people were, and Teneiya denied having any more people than were there at the moment. Savage was convinced that if he found the rest of the tribe he could persuade them to come with him back to the negotiations. The Major kidnapped some of the men, taking them with him to the north through the mountains and came upon the valley. This was the first entry into Yosemite Valley by any white men. Camping that night, the men debated what to call the valley they had just discovered. They agreed upon the name that the white men had already called the tribe, Yosemite. The date was March 25, 1851.[6] Once they reached the village of Teneiya's people a search was made but no more Indians were found there or in the valley at all. The soldiers returned to the meeting place but Chief Teneiya and the part of the tribe that was already in their custody escaped and returned to the mountains.

That May, a second expedition of militia travelled north to capture the chief and his band. Only a few indigenous people, among them two of Chief Teneiya's sons, were found. The chief was eventually brought in to find that his sons had been shot for trying to escape. Within a few days, the chief also tried to escape by jumping into the river.

After the recapture of Chief Teneiya, the rest of the band was found and brought to the Fresno reservation in the foothills. They then petitioned for their freedom to return to their mountain home and returned to their secluded valley of “Ahwahnee.”[6]

In 1852, a Mariposa expedition of US federal troops heard a report that Ahwahnechee Indians killed two European-American miners at Bridalveil Meadows. Soldiers were again dispatched and the troops executed five Ahwahnechee men.[7] Later, the tribe fled over the mountains to shelter with a neighboring people, the Mono tribe. They stayed the year and then returned to their native valley.

Later history

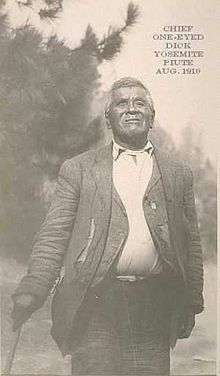

Chief Teneiya (d. 1853) was a leader in Yosemite Valley. His father was Ahwahnechee.[8] He led his band away from Yosemite to settle with Paiutes in eastern California.[9] Teneiya has descendants living today.

The official canon says that the Ahwahnechee of Yosemite "became extinct" as a people in the 19th century; however, the US federal government has evicted Yosemite Native people from the park in 1851, 1906, 1929, and 1969.[10]

Jay Johnson, an Ahwahnechee leader in the Mariposa Indian Council, hopes to get federal recognition for Yosemite Indians.[10]

Plant use

The Ahwahnechee performed controlled burns in the Yosemite Valley that controlled undergrowth and maintained the oak population. Acorns were a central staple to their diet. Black oak acorns provided almost 60% of their diet.[11] These acorns were taken out of a big stash and lain on a slab of rock in the sun to dry. Once they had dried, the acorns were ground up in small holes atop big granite slabs also called a mortar and pestal. Once they had been sufficiently ground down to a fine powder, the acorn “flour” was put into a shallow depression at the edge of the river. This depression was lined, often with nearby ferns, to keep the acorn powder from being lost in the sand. Rocks were then heated in a fire and placed into the small depression with the acorn flour to heat and potentially boil the bitter taste out, to make it more palatable. When soaked and edible, the flour, now turned to a mush due to the water, was taken out and put into willow cooking baskets. It was heated over a fire, and consumed either as a mush, or baked into a flat bread.[12]

National Park Service naturalist, Will Neely created a list of the plants commonly used by the Ahwahnechee. Black oak, sugar pine, western juniper, canyon live oak, interior live oak, foothill pine, buckeye, pinyon pine nuts provided acorns and seeds for food. Other plants provided smaller seeds. Mariposa tulip, golden brodiaea, common camas, squaw root, and Bolander's yampah provided edible bulbs and roots. Greens eaten by the Ahwahnechee included broad-leaved lupine, common monkey flower, nude buckwheat, California thistle, miner's lettuce, sorrel, clover, umbrella plant, crimson columbine, and alum root. Strawberry, blackberry, raspberry, thimbleberry, wild grape, gooseberry, currant, blue elderberry, western choke cherry, Sierra plum, and greenleaf manzanita provided berries and fruits.[11]

The Ahwahnechee brewed drinks from whiteleaf manzanita and western juniper. Commonly used medicine plants included Yerba santa, yarrow, giant hyssop, Brewer's angelica, sagebrush, showy milkweed, mountain dogbane, balsamroot, California barberry, fleabane, mint, knotweed, wild rose, meadow goldenrod, mule ears, pearly everlasting, and the California laurel.[11]

The tribe used soap plant and meadow rue to make soap. They used fibers from Mountain dogbane, showy milkweed, wild grape, and soap plant for cordage.[11]

Baskets were woven from splints of American dogwood, big-leaf maple, buckbrush, deer brush, willow, and California hazelnut[11] Additional bracken fern would add black colors to the basket and redbud would provide red.

The tribe made bows from incense-cedar, and Pacific dogwood. They built homes from Incense-cedar.[11]

Dwellings

The people lived in camps at the bottom of the valley, in huts known as o-chum. These small homes were built with pine for the framing and supports, using the wood in a teepee like structure with a diameter of about twelve feet. For the insulation of the homes, cedar bark was used to cover the pine poles to create a sturdy and durable covering for the family housed inside. There were two openings in the huts: One was big enough to be used as an entrance, and the latter is a small opening at the top of the teepee to allow some ventilation for smoke.

A small fire was built in the colder months, and easily kept the dwellers warm. These o-chums were able to provide housing to a family of six. To make the bedding, the natives would often use the skins of the animals that they shared the land with. The mattress was made from the skins of bigger animals such as bears and deer. And the blanket was made from the skins of smaller animals, cut into strips and woven together for extra warmth.

Another sort of building that the Ahwahnechees often used was a sweat house. These structures were somewhat similar to the o-chum except for the fact that the top, instead of being at a point, was rounded and the entire structure was covered with mud. The sweat houses were used by the young hunters, before they went on a trip, to rid their bodies of the human smell that could betray their presence to the prey. And provided the men with a way to relax and cleanse themselves for religious and health purposes.[12]

Hunting

When it came to game, the natives had a wide range of quarry. They hunted everything from deer and large game, to worms and small insects. The animals provided much more than just food. They provided skins for clothing, sinew for tying, and other purposes. The whole animal was used in some way, with little waste. Whatever meat that was not eaten right away was hung to dry and made into jerky for later consumption. The braves went on hunting trips that could take days or even weeks, trying to get enough to take back to the tribe without diminishing the future game supply.[12]

Ahwahnechee place names

Some Ahwahnechee tribal names for areas around Yosemite Valley include the following:

- Ahwahne: Yosemite Valley

- Tissaack (Tis-se'-yak): Half Dome (South Dome) - meaning “Face of a Young Woman Stained with Tears” for the dark vertical dripping stripes of lichens[13]

- Loya: Sentinel Rock

- Tutocanula or Tutockahnulah: El Capitan

- Ahwiyah: Mirror Lake

- Patillima or Ernating Lawootoo: Glacier Point

- Pohono: Bridalveil Fall

- Piwyack: Tenaya Lake

- Yonapah: Vernal Fall

- Yowihe: Nevada Fall

- Mahtah: Liberty Cap[14]

Namesakes

The Ahwahnee Hotel and Ahwahneechee Village, a recreated 19th-century tribal village in Yosemite Valley, are both named for the tribe, as are the Ahwahnee Heritage Days. Ahwahnee, California and Ahwahnee Estates, California are also named after the tribe.

Notes

- Northern Paiute Language Project

- "Above California". Above California. Archived from the original on 2007-02-17. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- Fragnoli, D. (2004). Naming yosemite. ATQ (The American Transcendental Quarterly), 18(4), 263.

- Wuerthner, George (1994). Yosemite: A Visitors Companion. Stackpole Books, p. 13

- Mazel, 100

- Bingaman, John W. The Ahwahnechees: A Story of Yosemite Indians. 1966. October 2014. <http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/the_ahwahneechees/chapter_1.html>.

- Mazel, 98-99

- L. H. Bunnell: Discovery of Yosemite: Chapter XVIII. Archived 2007-02-17 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved 8 Dec 2009)

- Mazel, 99

- Mazel, 162

- Schaffer, Jeffrey P. "The Living Yosemite–The Ahwahnechee." Archived 2014-05-28 at the Wayback Machine 100 Yosemite Hikes. (retrieved 8 Dec 2009)

- Wilson, Herbert Earl. The Lore and Lure of Yosemite. n.d.

- My Yosemite: A Guide for Young Adventurers, Mike Graf

- Jackson, Helen Hunt. "Bits of Travel at Home (1878)." Yosemite Online Library. (retrieved 10 Dec 2009)

References

- Mazel, David. American Literary Environmentalism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8203-2180-6.