Akkad (city)

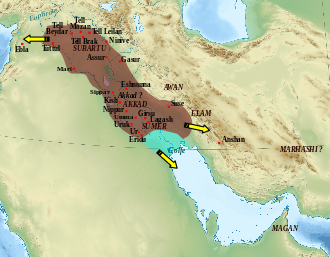

Akkad (/ˈækæd/; or Agade, cuneiform 𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠, A-ga-deki3 in Akkadian, also 𒌵𒆠 URIKI in Sumerian during the Ur III period)[1] was the name of a Mesopotamian city and its surrounding area.[2] Akkad was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, which was the dominant political force in Mesopotamia during a period of about 150 years in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC.

Its location is unknown, although there are a number of candidate sites, mostly situated east of the Tigris, roughly between the modern cities of Samarra and Baghdad.[3]

Textual sources

Before the decipherment of cuneiform in the 19th century, the city was known only from a single reference in Genesis 10:10[4] where it is written אַכַּד ( 'Akkad), rendered in the KJV as Accad. The name is given in a list of cities of Nimrod in Sumer (Shinar).

Sallaberger and Westenholz (1999) cite the number of 160 known mentions of the city in the extant cuneiform corpus, in sources ranging in date from the Old Akkadian period itself down to the Neo-Babylonian period. The name is spelled logographically as URIKI, or phonetically as a-ga-dèKI, variously transcribed into English as Akkad, Akkade or Agade.[5]

The etymology of the name is unclear, but not of Akkadian (Semitic) origin. Various suggestions have proposed Sumerian, Hurrian or Lullubian etymologies. The non-Akkadian origin of the city's name suggests that the site may have already been occupied in pre-Sargonic times, as also suggested by the mentioning of the city in one pre-Sargonic year-name.[6]

The inscription on the Bassetki Statue records that the inhabitants of Akkad built a temple for Naram-Sin after he had crushed a revolt against his rule.[7]

The main goddess of Akkad was Ishtar-Astarte (Inanna), who was called ‘Aštar-annunîtum or "Warlike Ishtar".[8] Her husband Ilaba was also revered in Akkad. Ishtar and Ilaba were later worshipped at Sippar in the Old Babylonian period, possibly because Akkad itself had been destroyed by that time.[5] The city was certainly in ruins by the mid-first millennium BC.[9]

Location

Many older proposals put Akkad on the Euphrates, but more recent discussions conclude that a location on the Tigris is more likely.[10]

The identification of Akkad with Sippar ša Annunîtum (modern Tell ed-Der), along a canal opposite Sippar ša Šamaš (Sippar, modern Tell Abu Habba) was rejected by Unger (1928) based on a Neo-Babylonian text (6th century BC) that lists Sippar ša Annunîtum and Akkad as separate places.[11]

Harvey Weiss (1975) proposed Ishan Mizyad, a large site 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) northwest from Kish.[12] Excavations have shown that the remains at Ishan Mizyad date to the Ur III period and not to the Akkadian period.[5]

Discussion since the 1990s has focused on sites along or east of the Tigris. Wall-Romana (1990) suggested a location near the confluence of the Diyala River with the Tigris, and more specifically Tell Muhammad in the south-eastern suburbs of Baghdad as the likeliest candidate for Akkad, although admitting that no remains datable to the Akkadian period had been found at the site.[13]

Sallaberger and Westenholz (1999) suggested a location close to the confluence of the ʿAdhaim river east of Samarra (at or near Dhuluiya).[3] Similarly, Reade (2002) suggested a site in this vicinity, by Qādisiyyah, based on a fragment of an Old Akkadian statue (now in the British Museum) found there.[14] This had been suggested much earlier by Lane.[15]

Based on an Old Babylonian period itinerary from Mari, Akkad would be on the Tigris just downstream of the current city of Baghdad. Mari documents also indicate that Akkad is sited at a river crossing.[16]

See also

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- History of Mesopotamia

References

- Miller, Douglas B.; Shipp, R. Mark (1996). An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List. Eisenbrauns. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-931464-86-7.

- Foster (2013): "Akkad was originally the name of an area and city near the confluence of the Diyala and Tigris rivers in Mesopotamia (Adams 1965; Weiss 1997). The meaning of the word is unknown. After it became the seat of the Sargonic Dynasty around 2300 bce, Akkad as a territory expanded to mean northern Babylonia, from north of Nippur to Sippar. The city of the same name is first attested in the late Early Dynastic period, became an imperial capital in the Sargonic period, and was still occupied in the second millennium. By the mid‐first millennium the city's cults had been transferred elsewhere and the former capital was a famous ruin. In modern scholarship, the city is often distinguished from the region by calling it Agade. Its location has not been identified."

- "Akkade may thus be one of the many large tells on the confluence of the Adheim River with the Tigris" (Sallaberger, and Westenholz 1999, p. 32.

- Genesis 10:10, King James Version (Oxford Standard, 1769)

- Sallaberger & Westenholz 1999, pp. 31–32

- Wall-Romana 1990, pp. 205–206

- van de Mieroop 2007, pp. 68–69

- Meador 2001, p. 8

- Foster 2013, p. 266

- Wall-Romana 1990, p. 209

- Unger 1928, p. 62

- Weiss 1975, p. 451

- Wall-Romana 1990, pp. 243–244

- Reade 2002, p. 269

- Lane, W. H., Babylonian Problems, John Murray, London, 1923

- Andrew George, "Babylonian and Assyrian: a history of Akkadian", In: Postgate, J. N. (ed.), Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2007, p. 35

Sources

- Foster, Benjamin R. (2013), "Akkad (Agade)", in Bagnall, Roger S. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Chicago: Blackwell, pp. 266–267, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah01005

- Meador, Betty De Shong (2001), Inanna, Lady of the Largest Heart. Poems by the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9

- Pruß, Alexander (2004), "Remarks on the Chronological Periods", in Lebeau, Marc; Sauvage, Martin (eds.), Atlas of Preclassical Upper Mesopotamia, Subartu, 13, pp. 7–21, ISBN 2503991203

- Reade, Julian (2002), "Early Monuments in Gulf Stone at the British Museum, with Observations on Some Gudea Statues and the Location of Agade", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, 92 (2): 258–295, doi:10.1515/zava.2002.92.2.258

- Sallaberger, Walther; Westenholz, Aage (1999), Mesopotamien: Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 160/3, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 352553325X

- Unger, Eckhard (1928), "Akkad", in Ebeling, Erich; Meissner, Bruno (eds.), Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), 1, Berlin: W. de Gruyter, p. 62, OCLC 23582617

- van de Mieroop, Marc (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. Second Edition, Blackwell History of the Ancient World, Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 9781405149112

- Wall-Romana, Christophe (1990), "An Areal Location of Agade", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 49 (3): 205–245, doi:10.1086/373442, JSTOR 546244

- Weiss, Harvey (1975), "Kish, Akkad and Agade", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (3): 434–453, doi:10.2307/599355, JSTOR 599355