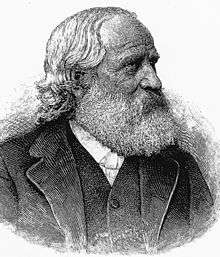

Adolph Douai

Karl Daniel Adolph Douai (1819 – 1888), known to his peers as "Adolph", was a German Texan teacher as well as a socialist and abolitionist newspaper editor. Douai was driven from Texas in 1856 due to his published opposition of slavery, living out the rest of his life as a school operator in the New England city of Boston. Douai is remembered as one of the leading American Marxists of the 19th century as well as a pioneer of the Kindergarten movement in America.

Biography

Early years

Karl Daniel Adolph Douai was born February 22, 1819, in Altenburg, Thuringia in the Duchy of Saxon-Altenburg, the son of a school teacher.[1] The Douai family was of French extraction, having fled to Dresden after the fall of the French Revolution.[1]

The Douai family was poor and Adolph went to work at the age of 8.[1] Nevertheless, as a boy he was well educated, graduating from the Altenburg Gymnasium and the University of Leipzig, where he studied philology and history.[2] He worked variously in his boyhood years as a newsboy, as an assistant to his father in teaching peasant children, as a crocheter of home manufactured wollen shawls, among other small jobs.[1]

Douai was poorly nourished as a child and short of stature, standing just 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 m) tall at age 19.[1]

While at university, Douai found the stipends insufficient and therefore sought to supplement his income by writing. In a short autobiography published at the time of his death, Douai claimed to have authored several novels and two theological papers during his undergraduate years.[1]

Following his graduation from the University of Leipzig, Douai sought admission to the University of Jena as a student of philosophy and pedagogy. He was denied admission, however, and was forced to enter the workforce to earn enough money to study as a paying student.[1] Douai took a job as a private tutor in Russia as the most lucrative course of employment during this interval. As he sought to be married to Baroness Agnes von Beust and faced a 2-year deadline for obtaining permanent employment placed upon him by her family, Douai instead took and passed imperial examinations at the University of Dorpat, which entitled him to the title of Doctor and enabled his employment by the government of Russia.[1]

Douai married Baroness Agnes von Beust on September 26, 1843, in the city of Königsberg. Together they eventually had ten children.

Life in Russia had a radicalizing impact upon Douai and after 5 years in the country he returned to his native Altenburg, convinced that a revolution for constitutional and democratic government was in the wings. There he bought a building and hired assistants and established a private preparatory school.[1]

With the coming of the Revolutions of 1848, Douai helped organize clubs for workers and students and took an active part in the political movement, sitting as a member of the revolutionary Landtag of Saxe-Altenberg.[1] His political activity brought him to the attention of the government of Saxony, which arrested him and charged him with high treason and rioting in the summer of 1848.[1] Douai prevailed on the charge of treason but was nevertheless sentenced to one year in prison on three of the counts against him, a result which forced him to close his school and disburse its property.[1]

Texas years

Following his release from prison,[2] Douai was pressured by the government to emigrate and did so. Douai came to the United States and made his new home in the country's new state of Texas in the German colony of New Braunfels.[3] There he helped to raise funds to launch the Neue Braunfelser Zeitung in November 1852, a publication edited by his friend Ferdinand Lindheimer (1801-1879).[4]

Douai also attempted to establish another school, but the efforts of the free-thinker Douai were impeded by a local Catholic priest, who spoke out against the schoolmaster, prompting parents to withdraw their children from his school.[1] Douai subsequently fell ill with cholera, resulting in the termination of the school.[1]

With his first business effort a failure, Douai moved to nearby San Antonio and turned his attention to newspaper work, launching a newspaper, the San Antonio Deutsche Zeitung (German News).[3] In his paper's pages, Douai unflinchingly denounced slavery as an evil incompatible with democracy and urged its abolition.[2] Douai advocated in favor of establishing a slavery free state in the territory of western Texas.[2] These controversial positions in slave-state Texas resulted in widespread public antipathy and the loss of advertisers and lead to the necessary sale of his publication in 1856.[1]

Northern years

With the American Civil War in the wind, Douai moved north to Boston, Massachusetts, where he began working as a private tutor, also teaching at a New England institute for the blind in South Boston.[1] While in Boston, Douai established a German workingmen's club which in 1859 sponsored a three-classroom school featuring the first Kindergarten in America.[1][2]

In 1860, Douai became editor of the New York Demokrat, a position which he soon abandoned to assume the position of Principal of the Hoboken Academy. He taught there for six years, moving to New York City in 1866 to establish a new school of his own.[1] This New York school lost its leased building as part of an expansion of Broadway in 1871, prompting Douai to move to Newark, New Jersey, to accept a post as principal of the Green Street School there. Douai remained in Newark in this position until 1876, at which time a new Board of Directors were elected who were opposed to him.[1]

After being removed from his position in Newark, Douai accepted an offer to start a new educational academy in Irvington, New Jersey, but no suitable building could be had to bring the project to fruition. This event essentially brought Douai's teaching career to a close.[1]

He was an early and prominent member of the Socialist Labor Party of America, the first Marxist political party in America, established as the "Workingmen's Party of the United States" in 1876.[5]

In the fall of 1877 there was a short-lived plan for Douai to serve as English-language translator of Das Kapital, the magnum opus of Karl Marx first published in 1867.[6] In January 1878, the German-language socialist daily newspaper the New Yorker Volkszeitung (New York People's News) was established, and Douai began to write extensively for the publication.[1] It was there that Douai gained his greatest public fame as a journalist and publicist.

Death and legacy

Adolph Douai died on January 21, 1888, in New York after having suffered chronic "throat trouble."[1] A public memorial was held January 23 at the Brooklyn Labor Lyceum.[1]

An unpublished typescript of an English translation of Adolph Douai's autobiography resides at the San Antonio Public Library.

Footnotes

- "Dr. Adolph Douai, the Gifted and Tireless Agitator Dead...," Workmen's Advocate [New Haven, CT], vol. 4, no. 4 (January 28, 1888), pp. 1-2.

- Marilyn M. Sibley, "Carl Daniel Adolph Douai," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, 2010.

- Glen E. Lich, The German Texans. San Antonio: University of Texas Institute of Texas Cultures, 1996; pg. 140.

- Marjorie Cook, "New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State HIstorical Society, 2010.

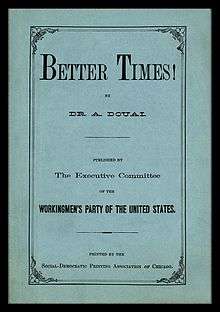

- Douai was the author of Better Times! (1876), called by historians Frank Girard and Ben Perry "one of the [Workingmen's Party's] first pamphlets." See: Frank Girard and Ben Perry, The Socialist Labor Party, 1876-1991: A Short History. Philadelphia: Livra Books, 1991; pg. 7.

- Karl Marx to Friedrich Adolph Sorge, September 27, 1877, and October 16, 1877. Published in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Marx-Engels Collected Works: Volume 45. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1991; pp. 276-277; 282-283.

Works

- A Practical and Complete German Grammar. Boston, MA: Crosby, Nichols, Lee & Co., 1858.

- The Kindergarten: A Manual for the Introduction of Froebel's System of Primary Education into Public Schools; and for the Use of Mothers and Private Teachers. New York: E. Steiger, 1872.

- Better Times! Chicago: Executive Committee, Workingmen's Party of the United States, n.d. [1876].

- "Labor and Work," Workmen's Advocate [New Haven, CT], vol. 3, no. 17 (April 23, 1887), pg. 1.

- "Testimony to the United States Senate on Behalf of the Socialist Labor Party of America," in Report of the Committee of the Senate upon the Relations of Labor and Capital and Testimony Taken by the Committee: In Five Volumes: Volume II – Testimony. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1885; pp. 702–743.

Further reading

- Justine Davis Randers-Pehrson, Adolf Douai, 1819-1888: The Turbulent Life of a German Forty-Eighter in the Homeland and in the United States. New York: Peter Lang, 2000.

- Paul Mitzenheim, "Adolf Douai: Vermittler Fröbelscher Ideen nach den USA und Japan." In Helmut Heiland and Karl Neumann (eds.): Friedrich Fröbel in Japan und Deutschland. Weinheim, Germany: Dt. Studien-Verlag, 1998.

- Carl Wittke, Refugees of Revolution: The German Forty-Eighters in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1952.

External links

- Bibliographic Listing of Adolph Douai's Autobiography, San Antonio Public Library, San Antonio, Texas. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- "Douai, Carl Daniel Adolph" in the Handbook of Texas Online