Admiralty M-N Scheme

'The Admiralty M-N Scheme' (sometimes given as "Project M-N") was a World War I British plan to close the Strait of Dover in the English Channel to German U-Boats, by means of a chain of either eight or twelve massive towers linked by anti-submarine booms and nets. Only two towers had been constructed before the Armistice with Germany caused the cancellation of the project.

Origin

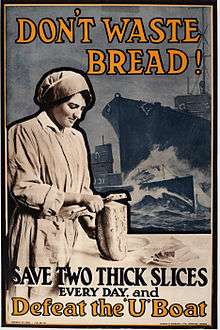

On 31 January 1917, it was announced to the German Reichstag that unrestricted submarine warfare would resume the next day, 1 February.[1] The renewed U-boat campaign was initially a great success; nearly 500,000 tons of shipping being sunk in both February and March, and 860,000 tons in April, when Britain's reserve of wheat fell to 6 weeks' supply.

The British Admiralty redoubled its efforts to find effective remedy. Attention turned to the Strait of Dover, which was used by U-boats based in Bruges in occupied Belgium, to gain fast access to the Atlantic trade routes and the busy Western Approaches. If it could be successfully closed to them, they would have to take the much longer "Northern Route" around the north of Scotland, and therefore be able to spend less time on patrol. Existing countermeasures were the Dover Patrol of cruisers and destroyers, and the Dover Barrage, a line of steel anti-submarine nets supplemented by minefields stretching across the Strait, patrolled by destroyers, armed trawlers and drifters equipped with powerful searchlights, work on which had started in 1915. Although this had been improved by use of the new Mark H2 mine from mid-1917, it was not initially very successful as there was no agreement on the depth at which the mines should be tethered.[2] Until December 1917, only two U-boats had been destroyed by the barrage. Furthermore, the patrolling vessels were vulnerable to attack by German torpedo boats,[3] as in the action of 26–27 October 1916, and the action of 20 April 1917.

The Engineer-in-Chief to the Admiralty, Sir Alexander Gibb, devised a scheme of eight or twelve large concrete and steel towers, placed at intervals on the sea bed across the Dover Strait from Folkestone to Cap Gris Nez. Stretched between the towers would be improved anti-submarine nets; each tower would be equipped with two 4-inch guns, searchlights and hydrophone detection equipment. Gibb had worked with T G Menzies and Colonel William McLellan on a submarine detection system based on a galvanometer, which was also to be incorporated.[4] There would be accommodation for 100 men on each of the towers.

Construction

In June 1918, an advance party of Royal Engineers arrived at Southwick Green in Sussex where they established a camp. Construction of the first two towers was soon underway on the south side of Shoreham harbour nearby, each one consisting of an 80 feet (25 metres) high reinforced concrete raft made from interlocking cells, surmounted by a 1,000 ton steel column 90 feet (27.5m) high and 40 feet (12m) wide. The cost of the whole project was £12 million, an enormous sum for the time. The towers became visible for many miles around and were known locally as the "Shoreham mystery towers". With the Armistice in November 1918, the whole project was cancelled; only Tower Number 1 was approaching completion.[5]

Legacy

The Number One tower soon found an alternative use as a replacement for the Nab Rock lightship, 40 miles away off Bembridge in the Isle of Wight. On 12 September 1920, it was towed out of Shoreham harbour by five Admiralty tugs, watched by a crowd of thousands and was sunk on a sand spit next to the rock on the following day. The Nab Tower is still in use today. The second tower remained at Shoreham until 1924 when it was demolished over a period of 6 months.[6] Amongst the Royal Engineer officers involved in the construction of the towers was Guy Maunsell who would later design the Maunsell Sea Forts in World War II.[7]

References

- This Day in History - 1 Feb 1917: Germany resumes unrestricted submarine warfare

- Robert M. Grant, U-Boats Destroyed: The Effect of Anti-Submarine Warfare 1914-1918, Periscope Publishing Ltd 2002 (pp. 74-75), ISBN 1-904381-00-6

- Lawrence Sondhaus, World War One: The Global Revolution, Cambridge University Press 2011 (p.287), ISBN 978-0-521-51648-8

- Engineering Timelines: Guy Maunsell Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Black Jack (Quarterly Magazine Southampton Branch World Ship Society) Issue No: 152 Autumn 2009: (p.6) SHOREHAM TOWERS - One of the Admiralty’s greatest engineering secrets, Reproduced from Engineering & Technology IET Magazine May 2009

- "This is Findon Village: Giants Codenamed M-N". Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Engineering Timelines: Guy Maunsell