Actaea racemosa

Actaea racemosa, the black cohosh, black bugbane, black snakeroot, or fairy candle (syn. Cimicifuga racemosa), is a species of flowering plant of the family Ranunculaceae. It is native to eastern North America from the extreme south of Ontario to central Georgia, and west to Missouri and Arkansas. It grows in a variety of woodland habitats, and is often found in small woodland openings. The roots and rhizomes were used in traditional medicine by Native Americans. Although its extracts are manufactured as herbal medicines and dietary supplements, black cohosh is not well-studied or recommended for safe and effective use in treating menopause symptoms or any disease.[2]

| Actaea racemosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Ranunculales |

| Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Genus: | Actaea |

| Species: | A. racemosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Actaea racemosa | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

Description

Black cohosh is a smooth (glabrous) herbaceous perennial plant that produces large, compound leaves from an underground rhizome, reaching a height of 25–60 cm (9.8–23.6 in).[3][4] The basal leaves are up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long and broad, forming repeated sets of three leaflets (tripinnately compound) having a coarsely toothed (serrated) margin. The flowers are produced in late spring and early summer on a tall stem, 75–250 cm (30–98 in) tall, forming racemes up to 50 cm (20 in) long. The flowers have no petals or sepals, and consist of tight clusters of 55–110 white, 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long stamens surrounding a white stigma. The flowers have a distinctly sweet, fetid smell that attracts flies, gnats, and beetles.[3] The fruit is a dry follicle 5–10 mm (0.20–0.39 in) long, with one carpel, containing several seeds.[5]

Taxonomy

The plant species has a history of taxonomic uncertainty dating back to Carl Linnaeus, who—on the basis of morphological characteristics of the inflorescence and seeds—had placed the species into the genus Actaea. This designation was later revised by Thomas Nuttall reclassifying the species to the genus Cimicifuga. Nuttall's classification was based solely on the dry follicles produced by black cohosh, which are typical of species in Cimicifuga.[5] However, recent data from morphological and gene phylogeny analyses demonstrate that black cohosh is more closely related to species of the genus Actaea than to other Cimicifuga species. This has prompted the revision to Actaea racemosa as originally proposed by Linnaeus.[5] Blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides), despite its similar common name belongs to another family, the Berberidaceae, is not closely related to black cohosh, and may be unsafe if used together.[6]

Cultivation

A. racemosa grows in dependably moist, fairly heavy soil. It bears tall tapering racemes of white midsummer flowers on wiry black-purple stems, whose mildly unpleasant, medicinal smell at close range gives it the common name "Bugbane". The drying seed heads stay handsome in the garden for many weeks. Its deeply cut leaves, burgundy colored in the variety "atropurpurea", add interest to gardens, wherever summer heat and drought do not make it die back, which make it a popular garden perennial. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[7]

Traditional medicine

Native Americans used black cohosh to treat gynecological and other disorders.[2][4][8] Following the arrival of European settlers in the U.S. who continued the use of black cohosh, the plant appeared in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia under the name "black snakeroot".[2] In the 19th century, the root was used to treat snakebite, inflamed lungs, and pain from childbirth.[9]

Black cohosh is used as a dietary supplement marketed mainly to women for treating gynecological problems,[4] but there is no high-quality scientific evidence to support such uses.[8][6][10]

Safety and health concerns

Rigorous studies on the long-term safety of using black cohosh, and its safety as a traditional medicine or dietary supplement, have not been published,[2][8][6] mainly because most black cohosh materials are harvested from the wild with lack of proper authentication and adulteration of commercial preparations by other plant species.[4][11] High doses of black cohosh may cause nausea, dizziness, visual effects, a lower heart rate, and increased perspiration.[8]

Worldwide, some 83 cases of liver damage, including hepatitis, liver failure, and elevated liver enzymes, have been associated with using black cohosh, although a cause-and-effect relationship remains undefined.[2] Women have taken black cohosh without reporting adverse health effects,[6] and a meta-analysis of clinical trials found no evidence that black cohosh preparations had adverse effects on liver function.[12] According to Cancer Research UK: "Doctors are worried that using black cohosh long term may cause thickening of the womb lining. This could lead to an increased risk of womb cancer." They also caution that people with liver problems should not take it as it can damage the liver,[6][13] although a 2011 meta-analysis of research evidence suggested this concern may be unfounded.[12] In 2007, the Australian Government warned that black cohosh may cause liver damage, although rarely, and should not be used without medical supervision.[14] Other studies concluded that liver damage from use of black cohosh is unlikely.[15]

Phytochemicals

Black cohosh contains diverse phytochemicals, such as polyphenols[16][17] and estrogen-like compounds (isoflavones) implicated in effects of black cohosh extracts on hot flashes in menopausal women, although there is no effect confirmed by high-quality clinical research.[6][8][18]

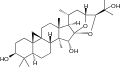

Cimigenol a constituent of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Cohosh)[19]

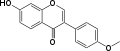

Cimigenol a constituent of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Cohosh)[19] Formononetin a constituent of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Cohosh)[19]

Formononetin a constituent of Cimicifuga racemosa (Black Cohosh)[19]

See also

- Caffeic acid

- Ferulic acid

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Phenylpropanoids

- Triterpenoids

References

- "International Plant Names Index". www.ipni.org.

- "Black cohosh: Fact sheet for health professionals". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 30 August 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Richo Cech (2002). Growing at-risk medicinal herbs. Horizon Herbs. pp. 10–27. ISBN 0-9700312-1-1.

- Predny ML, De Angelis P, Chamberlain JL (2006). "Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa): An annotated Bibliography". General Technical Report SRS–97. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station: 99. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- Compton JA, Culham A, Jury SL (1998). "Reclassification of Actaea to include Cimicifuga and Souliea (Ranunculaceae): Phylogeny inferred from morphology, nrDNA ITS, and epDNA trnL-F sequence variation". Taxon. 47 (3): 593–634. doi:10.2307/1223580. JSTOR 1223580.

- "Black cohosh". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Actaea racemosa". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Black cohosh". Drugs.com. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Niering, William A.; Olmstead, Nancy C. (1985) [1979]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. Knopf. p. 732. ISBN 0-394-50432-1.

- Leach, MJ; Moore, V (12 September 2012). "Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD007244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007244.pub2. PMC 6599854. PMID 22972105.

- Teschke R, Schmidt-Taenzer W, Wolff A (2011). "Herb induced liver injury presumably caused by black cohosh: a survey of initially purported cases and herbal quality specifications" (PDF). Annals of Hepatology. 10 (3): 249–59. doi:10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31536-4. PMID 21677326.

- Naser, Belal; Schnitker, Jörg; Minkin, Mary Jane; De Arriba, Susana Garcia; Nolte, Klaus-Ulrich; Osmers, Rüdiger (2011). "Suspected black cohosh hepatotoxicity". Menopause. 18 (4): 366–75. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181fcb2a6. PMID 21228727.

- "Black Cohosh". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa): New labelling requirements and consumer information for medicines containing Black cohosh". Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health, Australian Government. 29 May 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Teschke R, Schmidt-Taenzer W, Wolff A (2011). "Spontaneous reports of assumed herbal hepatotoxicity by black cohosh: is the liver-unspecific Naranjo scale precise enough to ascertain causality?". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 20 (6): 567–82. doi:10.1002/pds.2127. PMID 21702069.

- Viereck V, Emons G, Wuttke W (2005). "Black cohosh: just another phytoestrogen?". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 16 (5): 214–221. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.002. PMID 15927480.

- Nuntanakorn P, Jiang B, Yang H, Cervantes-Cervantes M, Kronenberg F, Kennelly EJ (2007). "Analysis of polyphenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity of four American Actaea species". Phytochem Anal. 18 (3): 219–28. doi:10.1002/pca.975. PMC 2981772. PMID 17500365.

- Hill, DA; Crider, M; Hill, SR (1 November 2016). "Hormone Therapy and Other Treatments for Symptoms of Menopause". American Family Physician. 94 (11): 884–889. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 27929271.

- Murray, edited by Joseph E. Pizzorno, Jr., Michael T. (2012). Textbook of natural medicine (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 661. ISBN 9781437723335.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Actaea racemosa. |