Achilles tendon rupture

Achilles tendon rupture is when the Achilles tendon, at the back of the ankle, breaks.[5] Symptoms include the sudden onset of sharp pain in the heel.[3] A snapping sound may be heard as the tendon breaks and walking becomes difficult.[4]

| Achilles tendon rupture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Achilles tendon tear,[1] Achilles rupture[2] |

| |

| The achilles tendon | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain in the heel[3] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[3] |

| Causes | Forced plantar flexion of the foot, direct trauma, long-standing tendonitis[4] |

| Risk factors | Fluoroquinolones, significant change in exercise, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, corticosteroids[1][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination, supported by medical imaging[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Achilles tendinitis, ankle sprain, avulsion fracture of the calcaneus[5] |

| Treatment | Casting or surgery[6][5] |

| Frequency | 1 per 10,000 people per year[5] |

Rupture typically occurs as a result of a sudden bending up of the foot when the calf muscle is engaged, direct trauma, or long-standing tendonitis.[4][5] Other risk factors include the use of fluoroquinolones, a significant change in exercise, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or corticosteroid use.[1][5] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and examination and supported by medical imaging.[5]

Prevention may include stretching before activity.[4] Treatment may be by surgery repair or casting with the toes somewhat pointed down.[6][2] Relatively rapid return to weight bearing (within 4 weeks) appears okay.[6][7] While surgery traditionally results in a small decrease in the risk of re-rupture, the risk of other complications is greater.[2] Additionally rapid rehabilitation may remove this difference in ruptures.[2] If appropriate treatment does not occur within 4 weeks of the injury outcomes are not as good.[8]

Achilles tendon rupture occurs in about 1 per 10,000 people per year.[5] Males are more commonly affected than females.[1] People in their 30s to 50s are most commonly affected.[5] The tendon itself was named in 1693 after the Greek hero Achilles.[9]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is typically the sudden onset of sharp pain in the heel.[3] A snapping sound may be heard as the tendon breaks and walking then becomes difficult.[4]

Causes

The Achilles tendon is most commonly injured by sudden plantarflexion or dorsiflexion of the ankle, or by forced dorsiflexion of the ankle outside its normal range of motion.

Other mechanisms by which the Achilles can be torn involve sudden direct trauma to the tendon, or sudden activation of the Achilles after atrophy from prolonged periods of inactivity. Some other common tears can occur from overuse while participating in intense sports. Twisting or jerking motions can also contribute to injury.

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics, famously ciprofloxacin, are known to increase the risk of tendon rupture, particularly Achilles.

People who commonly fall victim to Achilles rupture or tear include recreational athletes, people of old age, individuals with previous Achilles tendon tears or ruptures, previous tendon injections or quinolone use, extreme changes in training intensity or activity level, and participation in a new activity.

Most cases of Achilles tendon rupture are traumatic sports injuries. The average age of patients is 29–40 years with a male-to-female ratio of nearly 20:1. Direct steroid injections into the tendon have also been linked to rupture.

The use of quinolone antibiotics can cause several forms of tendinitis and tendon rupture, including rupture of the Achilles tendon. The risk is higher in people who are older than 60, who are also taking corticosteroids, or have kidney disease; it also increases with dose and taking them for longer periods of time. As of 2016 the mechanism through which quinolones cause this, was unclear.[10]

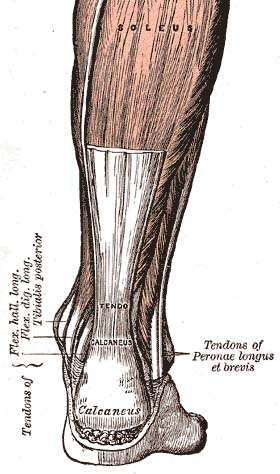

Anatomy

The Achilles tendon is the strongest and thickest tendon in the body, connecting the gastrocnemius, soleus and plantaris to the calcaneus. It is approximately 15 centimeters (5.9 inches) long and begins near the middle portion of the calf. Contraction of the gastrosoleus plantar flexes the foot, enabling such activities as walking, jumping, and running. The Achilles tendon receives its blood supply from its musculotendinous junction with the triceps surae and its innervation from the sural nerve and to a lesser degree from the tibial nerve.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be based on symptoms and the history of the event; typically people say it feels like being kicked or shot behind the ankle. Upon examination a gap may be felt just above the heel unless swelling has filled the gap and the Simmonds' test (aka Thompson test) will be positive; squeezing the calf muscles of the affected side while the person lies on their stomach, face down, with his feet hanging loose results in no movement (no passive plantarflexion) of the foot, while movement is expected with an intact Achilles tendon and should be observable upon manipulation of the uninvolved calf. Walking will usually be severely impaired, as the person will be unable to step off the ground using the injured leg. The person will also be unable to stand up on the toes of that leg, and pointing the foot downward (plantarflexion) will be impaired. Pain may be severe, and swelling is common.

Sometimes an ultrasound scan may be required to clarify or confirm the diagnosis and is recommended over MRI.[11] MRI is generally not needed.[12]

Imaging

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can be used to determine the tendon thickness, character, and presence of a tear. It works by sending extremely high frequencies of sound through the body. Some of these sounds are reflected back off the spaces between interstitial fluid and soft tissue or bone. These reflected images can be analyzed and computed into an image. These images are captured in real time and can be very helpful in detecting movement of the tendon and visualising possible injuries or tears. This device makes it very easy to spot structural damages to soft tissues, and consistent method of detecting this type of injury. This imaging modality is inexpensive, involves no ionizing radiation and, in the hands of skilled ultrasonographers, may be very reliable.

MRI can be used to discern incomplete ruptures from degeneration of the Achilles tendon, and MRI can also distinguish between paratenonitis, tendinosis, and bursitis. This technique uses a strong uniform magnetic field to align millions of protons running through the body. These protons are then bombarded with radio waves that knock some of them out of alignment. When these protons return they emit their own unique radio waves that can be analysed by a computer in 3D to create sharp cross sectional image of the area of interest. MRI can provide unparalleled contrast in soft tissue for an extremely high quality photograph making it easy for technicians to spot tears and other injuries.

Radiography can also be used to indirectly identify Achilles tears. Radiography uses X-rays to analyse the point of injury. This is not very effective at identifying injuries to soft tissue. X-rays are created when high energy electrons hit a metal source. X-ray images are acquired by utilising the different attenuation characteristics of dense (e.g. calcium in bone) and less dense (e.g. muscle) tissues when these rays pass through tissue and are captured on film. X-rays are generally exposed to optimise visualisation of dense objects such as bone while soft tissue remains relatively undifferentiated in the background. Radiography has little role in assessment of Achilles' tendon injury and is more useful for ruling out other injuries such as calcaneal fractures.[13]

Treatment

Treatment options include surgical and non-surgical approaches.[2] Surgery has traditionally been shown to have a lower risk of re-rupture however it has a higher rate of short term complications compared to non-surgical approaches.[2] Additionally certain rehabilitation techniques (early weight-bearing in an orthosis and early range of movement exercises) appear to have shown similar rates of re-rupture compared to surgery.[2]

In centers that do not have early range of motion rehabilitation available, surgical repair is preferred to decrease re-rupture rates.[14]

Surgery

There are two different types of surgeries; open surgery and percutaneous surgery.

During an open surgery an incision is made in the back of the leg and the Achilles tendon is stitched together. In a complete or serious rupture the tendon of plantaris or another vestigial muscle is harvested and wrapped around the Achilles tendon, increasing the strength of the repaired tendon.[15] If the tissue quality is poor, e.g. the injury has been neglected, the surgeon might use a reinforcement mesh (collagen, Artelon or other degradable material).

In percutaneous surgery, the surgeon makes several small incisions, rather than one large incision, and sews the tendon back together through the incision(s). Surgery may be delayed for about a week after the rupture to let the swelling go down.[16] For sedentary patients and those who have vasculopathy or risks for poor healing, percutaneous surgical repair may be a better treatment choice than open surgical repair.[17]

Rehabilitation

Non-surgical treatment used to involve very long periods in a series of casts, and took longer to complete than surgical treatment. But both surgical and non-surgical rehabilitation protocols have recently become quicker, shorter, more aggressive, and more successful. It used to be that patients who underwent surgery would wear a cast for approximately 4 to 8 weeks after surgery and were only allowed to gently move the ankle once out of the cast. Recent studies have shown that patients have quicker and more successful recoveries when they are allowed to move and lightly stretch their ankle immediately after surgery. To keep their ankle safe these patients use a removable boot while walking and doing daily activities. Modern studies including non-surgical patients generally limit non-weight-bearing (NWB) to two weeks, and use modern removable boots, either fixed or hinged, rather than casts. Physiotherapy is often begun as early as two weeks following the start of either kind of treatment.

There are three things that need to be kept in mind while rehabilitating a ruptured Achilles: range of motion, functional strength, and sometimes orthotic support. Range of motion is important because it takes into mind the tightness of the repaired tendon. When beginning rehab a patient should perform stretches lightly and increase the intensity as time and pain permits. Putting linear stress on the tendon is important because it stimulates connective tissue repair, which can be achieved while performing the “runners stretch,” (putting your toes a couple inches up the wall while your heel is on the ground). Doing stretches to gain functional strength are also important because it improves healing in the tendon, which will in turn lead to a quicker return to activities. These stretches should be more intense and should involve some sort of weight bearing, which helps reorient and strengthen the collagen fibers in the injured ankle. A popular stretch used for this phase of rehabilitation is the toe raise on an elevated surface. The patient is to push up onto the toes and lower his or her self as far down as possible and repeat several times. The other part of the rehab process is orthotic support. This doesn’t have anything to do with stretching or strengthening the tendon, rather it is in place to keep the patient comfortable. These are custom made inserts that fit into the patients shoe and help with proper pronation of the foot, which is otherwise a problem that can lead to problems with the Achilles.

To briefly summarize the steps of rehabilitating a ruptured Achilles tendon, you should begin with range of motion type stretching. This will allow the ankle to get used to moving again and get ready for weight bearing activities. Then there is functional strength, this is where weight bearing should begin in order to start strengthening the tendon and getting it ready to perform daily activities and eventually in athletic situations.[18][19]

References

- "Achilles Tendon Tears". MSD Manual Professional Edition. August 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Ochen, Yassine; Beks, Reinier B; van Heijl, Mark; Hietbrink, Falco; Leenen, Luke P H; van der Velde, Detlef; Heng, Marilyn; van der Meijden, Olivier; Groenwold, Rolf H H; Houwert, R Marijn (7 January 2019). "Operative treatment versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ: k5120. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5120. PMC 6322065.

- Hubbard, MJ; Hildebrand, BA; Battafarano, MM; Battafarano, DF (June 2018). "Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders". Primary Care. 45 (2): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. PMID 29759125.

- Gossman, WG; Bhimji, SS (January 2018). "Achilles Tendon, Rupture". StatPearls. PMID 28613594.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2015). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2016 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 19. ISBN 9780323378222.

- El-Akkawi, AI; Joanroy, R; Barfod, KW; Kallemose, T; Kristensen, SS; Viberg, B (March 2018). "Effect of Early Versus Late Weightbearing in Conservatively Treated Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 57 (2): 346–352. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2017.06.006. PMID 28974345.

- van der Eng, DM; Schepers, T; Goslings, JC; Schep, NW (2012). "Rerupture rate after early weightbearing in operative versus conservative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 52 (5): 622–8. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2013.03.027. PMID 23659914.

- Maffulli, N; Ajis, A (June 2008). "Management of chronic ruptures of the Achilles tendon". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 90 (6): 1348–60. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01241. PMID 18519331.

- Taylor, Robert B. (2017). The Amazing Language of Medicine: Understanding Medical Terms and Their Backstories. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 9783319503288.

- Bidell, MR; Lodise, TP (June 2016). "Fluoroquinolone-Associated Tendinopathy: Does Levofloxacin Pose the Greatest Risk?". Pharmacotherapy. 36 (6): 679–93. doi:10.1002/phar.1761. PMID 27138564.

- Dams, Olivier C.; Reininga, Inge H.F.; Gielen, Jan L.; van den Akker-Scheek, Inge; Zwerver, Johannes (2017). "Imaging Modalities in the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Achilles Tendon Ruptures: A Systematic Review". Injury. 48 (11): 2383–2399. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.09.013. ISSN 0020-1383. PMID 28943056.

- "American Podiatric Medical Association | Choosing Wisely". www.choosingwisely.org. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Achilles Tendon Injuries~differential at eMedicine

- Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M (December 2012). "Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 94 (23): 2136–43. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00917. PMC 3509775. PMID 23224384.

- "Achilles tendon rupture". Mayo Clinic. August 20, 2014.

- "Surgery for an Achilles Tendon Rupture". WebMD. January 3, 2013.

- Khan-Farooqi, Waqqar; Anderson, Robert B. (April 28, 2010). "Achilles tendon evaluation and repair". Rheumatology Network.

- Cluett, Jonathan (April 29, 2007). "Achilles Tendon Rupture: What is an Achilles Tendon Rupture".

- Christensen, K.D. (July 20, 2003). "Rehab of the Achilles Tendon". Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |