Acheiropoietos Monastery

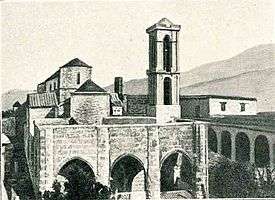

The Acheiropoietos Monastery (Greek: Μονή Ἀχειροποίητου, also Παναγία Ἀχειροποίητος and Acheripoetos) in Lambousa near the village of Karavas in the Kyrenia District, was a medieval Byzantine Orthodox Monastery.The monastery is currently under the conservation of the International Center for Heritage Studies of Girne American University.[1]

| Acheiropoietos Monastery | |

|---|---|

| Μονή Ἀχειροποίητου | |

| |

Acheiropoietos Monastery | |

| 35°21′10″N 33°11′26″E | |

| Location | Lambousa |

| Country | De jure De facto |

| Denomination | Greek Orthodox |

| History | |

| Founded | 11th century |

| Dedication | Virgin Mary |

| Cult(s) present | Holy Trinity |

| Relics held | Shroud of Joseph of Arimathea |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Byzantine architecture |

| Specifications | |

| Number of domes | 2 |

| Number of spires | 1 |

| Administration | |

| Metropolis | Church of Cyprus |

History

According to tradition, the monastery got its name from an acheiropoietos (meaning made without hands), an icon believed to have been miraculously moved from its original location in Asia Minor by the Virgin Mary in order to save it from destruction due to the Turkish conquest.[2][3]

The monastery soon gained prominence and eventually became the religious center of the region. The monastery was the headquarters of the Bishop of Lambousa, one of the 15 Bishops on the island until 1222.[4][5]

According to legend, the shroud of Joseph of Arimathea was once held in the monastery and was taken to Turin, Italy, in 1452 where it remains today and is now known as the Shroud of Turin.[4]

In 1735 the Russian Monk Vasily Barsky visited the monastery and noted that there were nine to ten monks on the premises.[6] Some years later, in about 1760, Petermann, a German traveler who visited the monastery in 1851, recalled that ninety years before his time Turkish raiders from Karaman had looted and burnt the monastery.[6] By the nineteenth century, the number of monks had been reduced further, and by the twentieth the monastery counted no resident monks.[4] Following independence, Greek soldiers were billeted in the residential buildings of the monastery and after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, the monastery became a military encampment and barracks for the Turkish Army.[6] The complex continues to be closed to the public.

Architecture

The Monastery was built in the 11th century on the foundations of a ruined 6th-century Christian church.[4] Through the centuries, constant rebuilding has given the complex different architectural styles from different time periods, including early Christian, Byzantine, Lusignan, Gothic and Frankish.[4][5] The present structure has two domes and a Gothic narthex.[6][7]

Lambousa Treasure

In 1897 a hoard of early Byzantine silver items was uncovered near the monastery. Known as the Lamboussa Treasure, or First Cyprus Treasure, it comprised a variety of liturgical objects dating from 6th or 7th century, perhaps deliberately hidden during the Arab invasion of Cyprus in 653 AD. The hoard was acquired by the British Museum in 1899.

External links

References

- "Faculty of Architecture, Design & Fine Arts The American University". Architecture.gau.edu.tr. Retrieved 2017-04-08.

- Darke, Diana (2008). North Cyprus : the Bradt travel guide (6th ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 152. ISBN 9781841622446.

Just 200m beyond the headland to the west, you can see the little churches of Akhiropitos Monastery and Ayios Eulalios, now unfortunately firmly within a military camp.

- "Ancient Cyprus in the British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Akhiropiitos Monastery,". A Guide for Residents and Visitors. Whatson-Northcyprus. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- "Girne'deki Diğer Gezilecek Yerler:" (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ΠΑΝΑΓΙΑ Η ΑΧΕΙΡΟΠΟΙΗΤΟΣ (ΛΑΠΗΘΟΥ ΚΥΠΡΟΣ) (in Greek). Retrieved 9 February 2013.

Μετά την Τουρκική εισβολή στη Κύπρο το Μοναστήρι λεηλατήθηκε και μετατράπηκε σε στρατώνα του Τουρκικού Στρατού και παραμείνει έτσι μέχρι σήμερα.

- Documents: working papers, 2002 ordinary session (third part). Council of Europe: Parliamentary Assembly. 2002. p. 114. ISBN 9789287149688. Retrieved 9 February 2013.