Abu Qubays, Syria

Abu Qubays (Arabic: أبو قبيس also spelled Abu Qobeis, Abu Qubais or Bu Kubais; also known as Qartal) is a former medieval castle and currently an inhabited village in northwestern Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate, located northwest of Hama. It is situated in the al-Ghab plain, west of the Orontes River. Nearby localities include Daliyah 21 kilometers to the west,[1] al-Laqbah to the south, Deir Shamil to the southeast, Tell Salhab to the northeast and Nahr al-Bared further northeast. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Abu Qubays had a population of 758 in the 2004 census.[2] Its inhabitants are predominantly Alawites.[3][4]

Abu Qubays أبو قبيس Qal'at Abu Qobeis | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Skyline of Abu Qubays fortress, 2004 | |

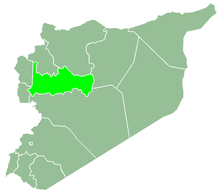

Abu Qubays Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 35°14′10″N 36°18′52″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Hama |

| District | Al-Suqaylabiyah |

| Subdistrict | Tell Salhab |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 758 |

History

Medieval era

Abu Qubays was originally built by the Arabs during the Abbasid era and was further strengthened by the Byzantines in the late 10th century. The castle was round, relatively small and overlooks the Orontes River.[5] During a second campaign against Muslim-held Syria by Byzantine emperor Basil II, Abu Qubays was burned along with a number of other fortresses in the province of Homs.[6]

Following the Crusader conquest of the coastal Levant in 1099, the Fatimid commander Iftikhar ad-Daula left his post in Jerusalem and moved to Abu Qubays of which he became lord,[7] along with the castles of al-Qadmus and al-Kahf.[8] The rulers of Abu Qubays, namely Iftikhar and his family, maintained a high income and social stature similar to the lords from the Banu Munqidh family of the Shaizar fortress to the south.[9] The Isma'ilis (known as the Assassins) purchased Abu Qubays,[1][5] as well as al-Qadmus and al-Kahf,[5] from Saif al-Mulk ibn Amrun, the local ruler of the Banu Munqidh family,[1] in the 1130s.[5] The Crusaders referred to it as Bokabeis.[10] The Isma'ilis of Abu Qubays paid a yearly tribute to the Knights Hospitallers of Margat (Qal'at Marqab),[1] a prominent Catholic military order, consisting of 800 gold pieces and a fixed number of bushels of barley and wheat.[1][11]

Nasih al-Din Khumartekin, a member of the Banu al-Daya nobility and lord of Abu Qubays—which was no longer under Isma'ili control—alerted Ayyubid sultan Saladin of an assassination attempt against him by the Isma'ilis during the unsuccessful siege against Zengid-held Aleppo on 11 May 1175. Khumartekin, who was in Saladin's camp, was killed by the group of Assassins after questioning them as they approached the camp. Saladin managed to avoid being harmed when they rushed towards him afterward and the attackers were slain by Saladin's guards.[12][13] In 1176 Sabiq al-Din was allotted Abu Qubays and Shaizar by Saladin after the latter freed him from Zengid imprisonment in Aleppo for opposing the ascension of al-Salih Isma'il al-Malik as ruler of that city.[14] By 1182, Mankarus, a son of Khumartekin, was lord of Abu Qubays and served as the commander of Saladin's troops in Hama.[15]

In 1222 the Shia Yemeni lord of Sinjar, al-Makzun al-Sinjari, led a force of roughly 50,000 fighters to support the Alawites of the coastal region against their Kurdish rivals after the latter had killed several Alawites celebrating Nowruz in the Sahyun Fortress. One of the fortresses he captured during the ensuing conquest was Abu Qubays.[16] In 1233 al-Aziz Muhammad, the Ayyubid ruler of Aleppo and successor of az-Zahir Ghazi, ended the semi-autonomous rule of the Banu al-Daya who had since repossessed the fortress, forcing their lord Shihab al-Din ibn al-Daya to relinquish both Abu Qubays and Shaizar after the latter slighted al-Aziz by not adequately abiding a request for supplies. He was allowed to keep his properties Aleppo in return for not putting up resistance to the Ayyubid army.[17] Damascus-born Arab geographer al-Dimashqi noted in 1300, during Mamluk rule, that Abu Qubays was one of several fortresses held by the Ismailis and that it was part of the Province of Tripoli.[18]

Ottoman era

The Levant was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1516 after Sultan Selim I's forces decisively defeated the Mamluk Sultanate at Marj Dabiq. After entering Aleppo, Sultan Selim waged a military campaign against the Alawites, summoning and executing 9,400 Alawite leaders and driving out the Alawite population from the coastal cities of Latakia and Jableh. Unable to subdue the Alawites in the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, their heartland, he dispatched thousands of Turkic tribes from Anatolia and Khurasan to the settle the region, establishing some of them in several of the mountainous area's most strategic fortresses, including in Abu Qubays, which was referred to as Qartal.[3]

Selim's strategy ultimately failed in the long-term as many of these tribes, particularly the Shia Muslim Turks of Khurasan, assimilated with the Alawite population. The Turks who originally resided in Abu Qubays, and who are Alawites in the present day, later became known as "Qaratila," deriving their name from "Qartal."[3] In 1785 Abu Qubays's inhabitants were unable to pay their land tax and as a result, sold one-third of their farmland to a Christian moneylender based in Hama, meeting the amount owed to the state treasury.[4]

Architecture

The castle at Abu Qubays is currently in a ruinous state, but most of its remains strongly indicate the architectural features typical of Isma'ili fortresses, namely small-sized and irregular masonry. It is circular in shape and consists of an exterior defensive wall with five towers, a small keep for provisions and residence and numerous subterranean storage chambers. The interior storage area is made up of a number rooms, a vaulted chamber and the ruins of a tower. The castle itself, situated on an eastern slope of the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, is surrounded by olive trees and overlooks the al-Ghab plain below.[1]

References

- Lee, p. 137.

- General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Hama Governorate. (in Arabic)

- Moosa, 1987, p. 275.

- Douwes, 2000, p. 185.

- Willey, p. 240.

- Bury, 1926, vol. 5, p. 252

- Nicolle, p. 91.

- Nicolle, p. 19.

- Tonghini, p. 17.

- Ball, 2007, p. 120.

- Boulanger, 1966, p. 451.

- Nicolle, 2011, p. 20

- Lyons, p. 87.

- Tonghini, p. 21.

- Lyons, p. 195.

- Friedman, p. 52.

- Tonghini, pp. 22-23.

- le Strange, 1890, p. 352.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abu Qobeis Castle. |

- Ball, Warwick (2007). Syria: A Historical and Architectural Guide. Interlink Books. ISBN 9781566566650.

Abu Qubais.

- Boulanger, Robert (1966). The Middle East, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran. Hachette.

- Douwes, Dick (2000). The Ottomans in Syria: a history of justice and oppression. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860640311.

- Friedman, Yaron (2010). The Nuṣayrī-ʻAlawīs: An Introduction to the Religion, History, and Identity of the Leading Minority in Syria. BRILL. ISBN 9004178929.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2005). The Leper King And His Heirs: Baldwin IV And the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521017475.

- Lee, Jess (2010). Syria Handbook. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1907263039.

- Lyons, M. C.; Jackson, D.E.P. (1982). Saladin: the Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31739-9.

- Moosa, Matti (1987). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2411-5.

- Nicolle, David (2003). The First Crusade 1096-99: Conquest of the Holy Land. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841765155.

- Nicolle, David (2011). Saladin: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1849083177.

- le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Tonghini, Cristina (2011). Shayzar I: The Fortification of the Citadel. BRILL. ISBN 9004217363.

- Willey, Peter; Institute of Ismaili Studies (2005). Eagle's nest: Ismaili castles in Iran and Syria. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.