Abraham Goldfaden

Abraham Goldfaden[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (born Avrum Goldnfoden; 24 July 1840 – 9 January 1908) was a Russian-born Jewish poet, playwright, stage director and actor in the languages Yiddish and Hebrew, author of some 40 plays. Goldfaden is considered the father of modern Jewish theatre.

Abraham Goldfaden | |

|---|---|

Abraham Goldfaden | |

| Born | Avrum Goldnfoden 24 July 1840 Starokostiantyniv, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) |

| Died | 9 January 1908 (aged 67) New York City, United States |

| Genre | |

| Years active | 1876–1908 |

In 1876 he founded in Romania what is generally credited as the world's first professional Yiddish-language theater troupe. He was also responsible for the first Hebrew-language play performed in the United States. The Avram Goldfaden Festival of Iaşi, Romania, is named and held in his honour.

Jacob Sternberg called him "the Prince Charming who woke up the lethargic Romanian Jewish culture."[1] Israil Bercovici wrote of his works: "we find points in common with what we now call 'total theater'. In many of his plays he alternates prose and verse, pantomime and dance, moments of acrobatics and some of jonglerie, and even of spiritualism..."[2]

Early life

Goldfaden was born in Starokonstantinov (Russia; present day Ukraine). His birthdate is sometimes given as July 12, following the "Old Style" calendar in use at that time in the Russian Empire. He attended a Jewish religious school (a cheder), but his middle-class family was strongly associated with the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, and his father, a watchmaker,[3] arranged that he receive private lessons in German and Russian. As a child, he is said to have appreciated and imitated the performances of wedding jesters and Brody singers to the degree that he acquired the nickname Avromele Badkhen, "Abie the Jester."[4] In 1857 he began studies at the government-run rabbinical school at Zhytomyr,[5] from which he emerged in 1866 as a teacher and a poet (with some experience in amateur theater), but he never led a congregation.

Goldfaden's first published poem was called "Progress"; his The New York Times obituary described it as "a plea for Zionism years before that movement developed."[6] In 1865 he published his first book of poetry, Tzitzim u-Ferahim (in Hebrew); The Jewish Encyclopedia (1901–1906) says that "Goldfaden's Hebrew poetry ... possesses considerable merit, but it has been eclipsed by his Yiddish poetry, which, for strength of expression and for depth of true Jewish feeling, remains unrivaled." The first book of verse in Yiddish was published in 1866, and in 1867 he took a job teaching in Simferopol.

A year later, he moved on to Odessa (in Ukraine). He lived initially in his uncle's house, where a cousin who was a good pianist helped him set some of his poems to music. In Odessa, Goldfaden renewed his acquaintance with fellow Yiddish-language writer Yitzkhok Yoel Linetzky, whom he knew from Zhytomyr[3] and met Hebrew-language poet Eliahu Mordechai Werbel (whose daughter Paulina would become Goldfaden's wife) and published poems in the newspaper Kol-Mevaser. He also wrote his first two plays, Die Tzwei Sheines (The Two Neighbors) and Die Murneh Sosfeh (Aunt Susie), included with some verses in a modestly successful 1869 book Die Yidene (The Jewish Woman), which went through three editions in three years. At this time, he and Paulina were living mainly on his meagre teacher's salary of 18 rubles a year, supplemented by giving private lessons and taking a job as a cashier in a hat shop.

In 1875, Goldfaden headed for Munich, intending to study medicine. This did not work out, and he headed for Lvov/Lemberg in Galicia, where he again met up with Linetsky, now editor of a weekly paper, Isrulik or Der Alter Yisrulik (which was well reputed, but was soon shut by the government). A year later, he moved on to Chernivtsi in Bukovina, where he edited the Yiddish-language daily Dos Bukoviner Israelitishe Folksblatt. The limits of the economic sense of this enterprise can be gauged from his inability to pay a registration fee of 3000 ducats. He tried unsuccessfully to operate the paper under a different name, but soon moved on to Iaşi on the invitation of Isaac Librescu (1850–1930), a young wealthy communitary activist interested in theatre.

Iaşi

Arriving in Iaşi (Jassy) in 1876, Goldfaden was fortunate to be better known as a good poet — many of whose poems had been set to music and had become popular songs — than as a less-than-successful businessman. Nevertheless, when he sought funds from Isaac Librescu for another newspaper, Librescu was uninterested in that proposition. Librescu's wife remarked that Yiddish-language journalism was just a way to starve; she suggested that there would be a lot more of a market for Yiddish-language theater. Librescu offered Goldfaden 100 francs for a public recital of his songs in the garden of Shimen Mark, Grădina Pomul Verde ("the Green Fruit-Tree Garden").

Instead of a simple recital, Goldfaden expanded the program into something of a vaudeville performance; either this or an indoor performance he and his fellow performers gave later that year in Botoşani is generally counted as the first professional Yiddish theatre performance. However, in the circumstances, the designation of a single performance as "the first" may be nominal: Goldfaden's first actor, Israel Grodner, was already singing Goldfaden's songs (and others) in the salons of Iaşi; also, in 1873, Grodner sang in a concert in Odessa (songs by Goldfaden, among others) that apparently included significant improvised material between songs, although no actual script.

Although Goldfaden, by his own account, was familiar at this time with "practically all of Russian literature", and also had plenty of exposure to Polish theater, and had even seen an African American tragedian, Ira Aldridge, performing Shakespeare,[3] the performance at Grădina Pomul Verde was only a bit more of a play than Grodner had participated in three years earlier. The songs were strung together with a bit of character and plot and a good bit of improvisation. The performance by Goldfaden, Grodner, Sokher Goldstein, and possibly as many as three other men went over well. The first performance was either Di bobe mitn einikl (Grandmother and Granddaughter) or Dos bintl holts (The Bundle of sticks); sources disagree. (Some reports suggest that Goldfaden himself was a poor singer, or even a non-singer and poor actor; according to Bercovici, these reports stem from Goldfaden's own self-disparaging remarks or from his countenance as an old man in New York, but contemporary reports show him to have been a decent, though not earth-shattering, actor and singer.)

After that time, Goldfaden continued miscellaneous newspaper work, but the stage became his main focus.

As it happens, the famous Romanian poet Mihai Eminescu, then journalist, saw one of the Pomul Verde performances later that summer. He records in his review that the company had six players. (A 1905 typographical error would turn this into a much-cited sixteen, suggesting a grander beginning for Yiddish theater.) He was impressed by the quality of the singing and acting, but found the pieces "without much dramatic interest.[7] His generally positive comments would seem to deserve to be taken seriously: Eminescu was known generally as "virulently antisemitic."[8] Eminescu appears to have seen four of Goldfaden's early plays: a satiric musical revue Di velt a gan-edn (The World and Paradise), Der farlibter maskil un der oyfgeklerter hosid (a dialogue between "an infatuated philosopher" and "an enlightened Hasid"), another musical revue Der shver mitn eidem (Father-in-law and Son-in-Law), and a comedy, Fishl der balegole un zayn knecht Sider (Fishel the Junkman and His Servant Sider).[7]

Searching for a theater

As the season for outdoor performances was coming to a close, Goldfaden tried and failed to rent an appropriate theater in Iaşi. A theatre owner named Reicher, presumably Jewish himself, told him that "a troupe of Jewish singers" would be "too dirty." Goldfaden, Grodner, and Goldstein headed first to Botoşani, where they lived in a garret and Goldfaden continued to churn out songs and plays. An initial successful performance of Di Rekruten (The Recruits) in an indoor theater ("with loges!" as Goldfaden wrote) was followed by days of rain so torrential that no one would come out to the theater; they pawned some possessions and left for Galaţi, which was to prove a bit more auspicious, with a successful three-week run.

In Galaţi they acquired their first serious set designer, a housepainter known as Reb Moishe Bas. He had no formal artistic training, but he proved to be good at the job, and joined the troupe, as did Sara Segal, their first actress. She was not yet out of her teens. After seeing her perform in their Galaţi premiere, her mother objected to her unmarried daughter cavorting on a stage like that. Goldstein – who, unlike Goldfaden and Grodner, was single – promptly married her and she remained with the troupe. (Besides being known as Sara Segal and Sofia Goldstein, she became best known as Sofia Karp, after a second marriage to actor Max Karp.)

After the successful run in Galaţi came a less successful attempt in Brăila, but by now the company had honed its act and it was time to go to the capital, Bucharest.

Bucharest

As in Iaşi, Goldfaden arrived in Bucharest with his reputation already established. He and his players performed first in the early spring at the salon Lazăr Cafegiu on Calea Văcăreşti (Văcăreşti Avenue, in the heart of the Jewish quarter), then, once the weather turned warm, at the Jigniţa garden, a pleasant tree-shaded beer garden on Str. Negru Vodă that up until then had drawn only a neighborhood crowd. He filled out his cast from the great pool of Jewish vocal talent: synagogue cantors. He also recruited two eminently respectable classically trained prima donnas, the sisters Margaretta and Annetta Schwartz.

Among the cantors in his casts that year were Lazăr Zuckermann (also known as Laiser Zuckerman; as a song-and-dance man, he would eventually follow Goldfaden to New York and have a long stage career),[9] Moishe Zilberman (also known as Silberman), and Simhe Dinman, as well as the 18-year-old Zigmund Mogulescu (Sigmund Mogulesko), who soon became a stage star. Orphaned by his teen years, Mogulescu had already made his way in the world as a singer – not only as a soloist in the Great Synagogue of Bucharest but also as a performer in cafes, at parties, with a visiting French operetta company, and even in a church choir. Before his voice changed, he had sung with Zuckerman, Dinman, and Moses Wald in the "Israelite Chorus," performing at important ceremonies in the Jewish community. Mogulescu's audition for Goldfaden was a scene from Vlăduţu Mamei (Mama's Boy), which formed the basis later that year for Goldfaden's light comedy Shmendrik, oder Die Komishe Chaseneh (Shmendrik or The Comical Wedding), starring Mogulescu as the almost painfully clueless and hapless young man (a role later famously played in New York and elsewhere by actress Molly Picon).

This recruiting of cantors was not without controversy: Cantor Cuper (also known as Kupfer), the head cantor of the Great Synagogue, considered it "impious" that cantors should perform in a secular setting, to crowds where both sexes mingled freely, keeping people up late so that they might not be on time for morning prayers.

While one may argue over which performance "started" Yiddish theater, by the end of that summer in Bucharest Yiddish theater was an established fact. The influx of Jewish merchants and middlemen to the city at the start of the Russo-Turkish War had greatly expanded the audience; among these new arrivals were Israel Rosenberg and Jacob Spivakovsky, the highly cultured scion of a wealthy Russian Jewish family, both of whom actually joined Goldfaden's troupe, but soon left to found the first Yiddish theater troupe in Imperial Russia.[10]

Goldfaden was churning out a repertoire – new songs, new plays, and translations of plays from Romanian, French, and other languages (in the first two years, he wrote 22 plays, and would eventually write about 40) – and while he was not always able to retain the players in his company once they became stars in their own right, he continued for many years to recruit first-rate talent, and his company became a de facto training ground for Yiddish theater. By the end of the year, others were writing Yiddish plays as well, such as Moses Horowitz with Der tiranisher bankir (The Tyrannical Banker), or Grodner with Curve un ganev (Prostitute and Thief), and Yiddish theater had become big theater, with elaborate sets, duelling choruses, and extras to fill out crowd scenes.

Goldfaden was helped by Ion Ghica, then head of the Romanian National Theater to legally establish a "dramatic society" to handle administrative matters. From those papers, we know that the troupe at the Jigniţa included Moris Teich, Michel Liechman (Glückman), Lazăr Zuckermann, Margareta Schwartz, Sofia Palandi, Aba Goldstein, and Clara Goldstein. We also know from similar papers that when Grodner and Mogulescu walked out on Goldfaden to start their own company, it included (besides themselves) Israel Rosenberg, Jacob Spivakovsky, P. Şapira, M. Banderevsky, Anetta Grodner, and Rosa Friedman.

Ion Ghica was a valuable ally for Yiddish theater in Bucharest. On several occasions he expressed his favorable view of the quality of acting, and even more of the technical aspects of the Yiddish theater. In 1881, he obtained for the National Theater the costumes that had been used for a Yiddish pageant on the coronation of King Solomon, which had been timed in tribute to the actual coronation of Carol I of Romania.

Turning serious

While light comedy and satire might have established Yiddish theater as a commercially successful medium, it was Goldfaden's higher aspirations for it that eventually earned him recognition as "the Yiddish Shakespeare."[6] As a man broadly read in several languages, he was acutely aware that there was no Eastern European Jewish tradition of dramatic literature – that his audience was used to seeking just "a good glass of Odobeşti and a song." Years later, he would paraphrase the typical Yiddish theatergoer of the time as saying to him: "We don't go to the theater to make our head swim with sad things. We have enough troubles at home... We go to the theater to cheer ourselves up. We pay up a coin and hope to be distracted, we want to laugh from the heart."

Goldfaden wrote that this attitude put him "pure and simply at war with the public." His stage was not to be merely "a masquerade"; he continued: "No, brothers. If I have arrived at having a stage, I want it to be a school for you. In youth you didn't have time to learn and cultivate yourself... Laugh heartily if I amuse you with my jokes, while I, watching you, feel my heart crying. Then, brothers, I'll give you a drama, a tragedy drawn from life, and you, too, shall cry – while my heart shall be glad." Nonetheless, his "war with the public" was based on understanding that public. He would also write, "I wrote Di kishefmakhern (The Witch) in Romania, where the populace – Jews as much as Romanians – believe strongly in witches." Local superstitions and concerns always made good subject matter, and, as Bercovici remarks, however strong his inspirational and didactic intent, his historical pieces were always connected to contemporary concerns.

Even in the first couple of years of his company, Goldfaden did not shy away from serious themes: his rained-out vaudeville in Botoşani had been Di Rekruten (The Recruits), playing with the theme of the press gangs working the streets of that town to conscript young men into the army. Before the end of 1876, Goldfaden had already translated Desolate Island by August von Kotzebue; thus, a play by a German aristocrat and Russian spy became the first non-comic play performed professionally in Yiddish. After his initial burst of mostly vaudevilles and light comedies (although Shmendrik and The Two Kuni-Lemls were reasonably sophisticated plays), Goldfaden would go on to write many serious Yiddish-language plays on Jewish themes, perhaps the most famous being Shulamith, also from 1880. Goldfaden himself suggested that this increasingly serious turn became possible because he had educated his audience. Nahma Sandrow suggests that it may have had equally as much to do with the arrival in Romania, at the time of the Russo-Turkish War, of Russian Jews who had been exposed to more sophisticated Russian language theater. Goldfaden's strong turn toward almost uniformly serious subject matter roughly coincided with bringing his troupe to Odessa.[4]

Goldfaden was both a theoretician and a practitioner of theater. That he was in no small measure a theoretician – for example, he was interested almost from the start in having set design seriously support the themes of his plays – relates to a key property of Yiddish theater at the time of its birth: in general, writes Bercovici, theory ran ahead of practice. Much of the Jewish community, Goldfaden included, were already familiar with contemporary theater in other languages. The initial itinerary of Goldfaden's company – Iaşi, Botoşani, Galaţi, Brăila, Bucharest – could as easily have been the itinerary of a Romanian-language troupe. Yiddish theater may have been seen from the outset as an expression of a Jewish national character, but the theatrical values of Goldfaden's company were in many ways those of a good Romanian theater of the time. Also, Yiddish was a German dialect which became a well-known language even among non-Jews in Moldavia (and Transylvania), an important language of commerce; the fact that one of the first to write about Yiddish theater was Romania's national poet, Mihai Eminescu, is testimony that interest in Yiddish theater went beyond the Jewish community.

Almost from the first, Yiddish theater drew a level of theater criticism comparable to any other European theater of its time. For example, Bercovici cites a "brochure" by one G. Abramski, published in 1877, that described and gave critiques of all of Goldfaden's plays of that year. Abramski speculated that the present day might be for Yiddish theater a moment comparable to the Elizabethan era for English theater. He discussed what a Yiddish theater ought to be, noted its many sources (ranging from Purim plays to circus pantomime), and praised its incorporation of strong female roles. He also criticized where he saw weaknesses, noting how unconvincingly a male actor played the mother in Shmendrik, or remarking of the play Di shtume kale (The Mute Bride) — a work that Goldfaden apparently wrote to accommodate a pretty, young actress who in the performance was too nervous to deliver her lines — that the only evidence of Goldfaden's authorship was his name.

Russia

Goldfaden's father wrote him to solicit the troupe to come to Odessa in Ukraine, which was then part of Imperial Russia. The timing was opportune: the end of the war meant that much of his best audience were now in Odessa rather than Bucharest; Rosenberg had already quit Goldfaden's troupe and was performing the Goldfadenian repertoire in Odessa.

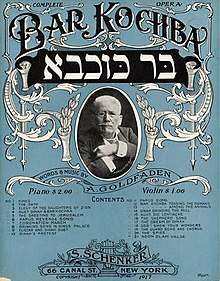

With a loan from Librescu, Goldfaden headed east with a group of 42 people, including performers, musicians, and their families. After the end of the Russo-Turkish War he and his troupe travelled extensively through Imperial Russia, notably to Kharkov (also in Ukraine), Moscow, and Saint Petersburg. Jacob Adler later described him at this time as "a bon vivant," "a cavalier," "as difficult to approach as an emperor."[11] He continued to turn out plays at a prolific pace, now mostly serious pieces such as Doctor Almasada, oder Die Yiden in Palermo (Doctor Almasada, or The Jews of Palermo), Shulamith, and Bar Kokhba, the last being a rather dark operetta about Bar Kokhba's revolt, written after the pogroms in Russia following the 1881 assassination of Czar Alexander II.

As it happens, a Frenchman named Victor Tissot happened to be in Berdichev when Goldfaden's company was there. He saw two plays – Di Rekruten, first premiered in Botoşani, and the later Di Shvebleh (Matches), a play of intrigue. Tissot's account of what he saw gives an interesting picture of the theaters and audiences Goldfaden's troupe encountered outside of the big cities. "Berdichev," he begins, "has not one cafe, not one restaurant. Berdichev, which is a boring and sad city, nonetheless has a theatrical hall, a big building made of rough boards, where theater troupes passing through now and then put on a play." Although there was a proper stage with a curtain, the cheap seats were bare benches, the more expensive ones were benches covered in red percale. Although there were many full beards, "there were no long caftans, no skullcaps." Some of the audience were quite poor, but these were assimilated Jews, basically secular. The audience also included Russian officers with their wives or girlfriends.

In Russia, Goldfaden and his troupe drew large audiences and were generally popular with progressive Jewish intellectuals, but slowly ran afoul of both the Czarist government and conservative elements in the Jewish community. Goldfaden was calling for change in the Jewish world:

- Wake up my people

- From your sleep, wake up

- And believe no more in foolishness.

A call like this might be a bit ambiguous, but it was unsettling to those who were on the side of the status quo. Yiddish theater was banned in Russia starting September 14, 1883, as part of the anti-Jewish reaction following the assassination of Czar Alexander II. Goldfaden and his troupe were left adrift in Saint Petersburg. They headed various directions, some to England, some to New York City, some to Poland, some to Romania.

The prophet adrift

While Yiddish theater continued successfully in various places, Goldfaden was not on the best terms at this time with Mogulescu. They had quarrelled (and settled) several times over rights to plays, and Mogulescu and his partner Moishe "Maurice" Finkel now dominated Yiddish theater in Romania, with about ten lesser companies competing as well. Mogulescu was a towering figure in Bucharest theater at this point, lauded on a level comparable to the actors of the National Theater, performing at times in Romanian as well as Yiddish, drawing an audience that went well beyond the Jewish community.

Goldfaden seems, in Bercovici's words, to have lost "his theatrical elan" in this period. He briefly put together a theater company in 1886 in Warsaw, with no notable success. In 1887 he went to New York (as did Mogulescu, independently). After extensive negotiations and great anticipation in the Yiddish-language press in New York ("Goldfaden in America," read the headline in the 11 January 1888 edition of the New Yorker Yiddishe Ilustrirte Zaitung), he briefly took on the job of director of Mogulescu's new "Rumanian Opera House"; they parted ways again after the failure of their first play, whose production values were apparently not up to New York standards. Goldfaden attempted (unsuccessfully) to found a theater school, then headed in 1889 for Paris, rather low on funds. There he wrote some poetry, worked on a play that he didn't finish at that time, and put together a theater company that never got to the point of putting on a play (because the cashier made off with all of their funds).[12] In October 1889 he scraped together the money to get to Lvov, where his reputation as a poet again came to his rescue.

Lviv

Lviv was not exactly a dramatist's dream. Leon Dreykurs described audiences bringing meals into the theater, rustling paper, treating the theater like a beer garden. He also quotes Jacob Schatzky: "All in all, the Galician milieu was not favorable to Yiddish theater. The intellectuals were assimilated, but the masses were fanatically religious and they viewed Jewish 'comedians' with disdain."[13]

Nonetheless, Iacob Ber Ghimpel, who owned a Yiddish theater there, was glad to have a figure of Goldfaden's stature. Goldfaden completed the play he'd started in Paris, Rabi Yoselman, oder Die Gzerot fun Alsas ("Rabbi Yoselman, or The Alsatian Decree"), in five acts and 23 scenes, based on the life of Josel of Rosheim. At this time he also wrote an operetta Rothschild and a semi-autobiographical play called Mashiach Tzeiten (Messiah Times) that gave a less-than-optimistic view of America.

Kalman Juvelier, an actor in Ber Ghimpel's company, credited Goldfaden with greatly strengthening the caliber of performance in Lviv during his brief time there, reporting that Goldfaden worked with every actor on understanding his or her character, so as to ensure that the play was more than just a series of songs and effects, and was respected by all.[13]

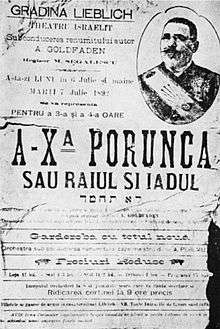

Bucharest

Buoyed by his success in Lvov, he returned to Bucharest in 1892, as director of the Jigniţa theater. His new company again included Lazăr Zuckermann; other players were Marcu (Mordechai) Segalescu, and later Iacob Kalich, Carol Schramek, Malvina Treitler-Löbel and her father H. Goldenbers. Among his notable plays from this period were Dos zenteh Gebot, oder Lo tachmod (The Tenth Commandment, or Thou Shalt Not Covet), Judas Maccabaeus, and Judith and Holofernes and a translation of Johann Strauss's Gypsy Baron.[14]

However, it was not a propitious time to return to Romania. Yiddish theater had become a business there, with slickly written advertisements, coordinated performances in multiple cities using the same publicity materials, and cutthroat competition: on one occasion in 1895, a young man named Bernfeld attended multiple performances of Goldfaden's Story of Isaac, memorized it all (including the songs), and took the whole package to Kalman Juvilier, who put on an unauthorized production in Iaşi. Such outright theft was possible because once Ion Ghica headed off on a diplomatic career, the National Theater, which was supposed to adjudicate issues like unauthorized performances of plays, was no longer paying much attention to Yiddish theater. (Juvilier and Goldfaden finally reached an out-of-court settlement.)[15]

Cutthroat competition was nothing to what was to follow. The 1890s were a tough time for the Romanian economy, and a rising tide of anti-Semitism made it an even tougher time for the Jews. One quarter of the Jewish population emigrated, with intellectuals particularly likely to leave, and those intellectuals who remained were more interested in politics than in theater: this was a period of social ferment, with Jewish socialists in Iaşi starting Der Veker (The Awakener).

Goldfaden left Romania in 1896; soon Juvilier's was the only active Yiddish theater troupe in the country, and foreign troupes had almost entirely ceased coming to the country. Although Lateiner, Horowitz, and Shumer kept writing, and occasionally managed to put on a play, it was not a good time for Yiddish theater – or any theater – in Romania, and would only become worse as the economy continued to decline.

Goldfaden wandered Europe as a poet and journalist. His plays continued to be performed in Europe and America, but rarely, if ever, did anyone send him royalties. His health deteriorated – a 1903 letter refers to asthma and spitting up blood – and he was running out of money. In 1903, he wrote Jacob Dinesohn from Paris, authorizing him to sell his remaining possessions in Romania, clothes and all. This gave him the money to head once more to New York in 1904.

New York City

In America, he again tried his hand at journalism, but a brief stint as editor of the New Yorker Yiddishe Ilustrirte Zaitung resulted only in getting the paper suspended and landing himself a rather large fine. On March 31, 1905, he recited poetry at a benefit performance at Cooper Union to raise a pension for Yiddish poet Eliakum Zunser, even worse off than himself because he had found himself unable to write since coming to America in 1889. Shortly afterwards, he met a group of young people who had a Hebrew language association at the Dr. Herzl Zion Club, and wrote a Hebrew-language play David ba-Milchama (David in the War), which they performed in March 1906, the first Hebrew-language play to be performed in America. Repeat performances in March 1907 and April 1908 drew successively larger crowds.

He also wrote the spoken portions of Ben Ami, loosely based on George Eliot's Daniel Deronda. After Goldfaden's former bit player Jacob Adler — by now the owner of a prominent New York Yiddish theater — optioned and ignored it, even accusing Goldfaden of being "senile," it premiered successfully at rival Boris Thomashefsky's People's Theater December 25, 1907, with music by H. Friedzel and lyrics by Mogulescu, who was by this time an international star.[16]

Goldfaden died in New York City in 1908. A contemporary account in The New York Times estimated that 75,000 people turned out for his funeral, joining the procession from the People's Theater on Bowery to Washington Cemetery in Brooklyn;[17] in recent scholarship the number of mourners has been given as 30,000.[18] In a follow-up article The New York Times called him "both a poet and a prophet," and noted that "there was more evidence of genuine sympathy with and admiration for the man and his work than is likely to be manifested at the funeral of any poet now writing in the English language in this country."[19]

In November 2009, Goldfaden was the subject of postage stamps issued jointly by Israel and Romania.

Zionism

Goldfaden had an on-again off-again relationship with Zionism. Some of his earliest poetry was Zionist avant la lettre and one of his last plays was written in Hebrew; several of his plays were implicitly or explicitly Zionist (Shulamith set in Jerusalem, Mashiach Tzeiten?! ending with its protagonists abandoning New York for Palestine); he served as a delegate from Paris to the World Zionist Congress in 1900.[20] Still, he spent most of his life (and set slightly more than half of his plays) in the Pale of Settlement and in the adjoining Jewish areas in Romania, and when he left it was never to go to Palestine, but to cities such as New York, London or Paris. This might be understandable when the number of his potential Jewish spectators in Palestine in his time was very small.

Works

Plays

Sources disagree about the dates (and even the names) of some of Goldfaden's plays. The titles here represent YIVO Yiddish>English transliteration, though other variants exist.

- Di Mumeh Soseh (Aunt Susie) wr. 1869[21][22]

- Di Tzvey Sheynes (The Two Neighbours) wr. 1869[21] (possibly the same as Di Sheynes 1877[23]

- Polyeh Shikor (Polyeh, the Drunkard) 1871[21]

- Anonimeh Komedyeh (Anonymous Comedy) 1876[21]

- Di Rekruten (The Recruits) 1876,[23] 1877[21]

- Dos Bintl Holtz (The Bundle of Sticks) 1876[23]

- Fishl der balegole un zayn knecht Sider (Fishel the Junkman and His Servant Sider) 1876[23]

- Di Velt a Gan-Edn (The World and Paradise) 1876[23]

- Der Farlibter Maskil un der Oifgeklerter Hosid (The Infatuated Philosopher and the Enlightened Hasid) 1876[23]

- Der Shver mitn eydem (Father-in-Law and Son-in-Law) 1876[23]

- Di Bobeh mit dem Eynikel (The Grandmother and the Granddaughter) 1876,[23] 1879[21]

- The Desolate Isle, Yiddish translation of a play by August von Kotzebue, 1876[23]

- Di Intrigeh oder Dvosye di pliotkemahern (The Intrigue or Dvoisie Intrigued) 1876,[21] 1877[23]

- A Gloz Vaser (A Glass of Water) 1877[23]

- Hotye-mir un Zaytye-mir (Leftovers) 1877[23]

- Shmendrik, oder Di komishe Chaseneh (Schmendrik or The Comical Wedding) 1877,[23] 1879[21]

- Shuster un Shnayder (Shoemaker and Tailor) 1877[23]

- Di Kaprizneh Kaleh, oder Kaptsnzon un Hungerman (The Capricious Bride or Pauper-son and Hunger-man) 1877[23][24] presumably the same play as Di kaprizneh Kaleh-Moyd (The Capricious Bridemaid) 1887[21]

- Yontl Shnayder (Yontl the Tailor) 1877[23]

- Vos tut men? (What Did He Do?) 1877[23]

- Di Shtumeh Kaleh (The Mute Bride) 1877,[23] 1887[21]

- Di Tsvey Toybe (The Two Deaf Men) 1877[23]

- Der Gekoyfter Shlof (The Purchased Sleep) 1877[23]

- Di Sheynes (The Neighbors) 1877[23]

- Yukel un Yekel (Yukel and Yekel) 1877[23]

- Der Katar (Catarrh) 1877[23]

- Iks-Miks-Driks, 1877[23]

- Di Mumeh Sose (Aunty Susie) 1877[23]

- Brayndele Kozak (Breindele Cossack), 1877[21][23]

- Der Podriatshik (The Purveyor), 1877[23]

- Di Alte Moyd (The Old Maid) 1877[23]

- Di Tsvey fardulte (The Two Scatter-Brains) 1877[23]

- Di Shvebeleh (Matches) 1877[23]

- Fir Portselayene Teler (Four Porcelain Plates) 1877[23]

- Der Shpigl (The Mirror) 1877[23]

- Toib, Shtum un Blind (Deaf, Dumb and Blind) 1878[23]

- Der Ligner, oder Todres Bloz (The Liar, or, Todres, Blow) (or Todres the Trombonist) 1878[23]

- Ni-be-ni-me-ni-cucurigu (Not Me, Not You, Not Cock-a-Doodle-Doo or Neither This, Nor That, nor Kukerikoo; Lulla Rosenfeld also gives the alternate title The Struggle of Culture with Fanaticism) 1878[23]

- Der Heker un der Bleher-yung (The Butcher and the Tinker) 1878[23]

- Di Kishefmakhern (The Sorceress, also known as The Witch of Botoşani) 1878,[23] 1887[21]

- Soufflé, 1878[23]

- Doy Intriganten (Two Intriguers) 1878[23]

- Di tsvey Kuni-lemels (The Fanatic, or The Two Kuni-Lemls) 1880[21][24]

- Tchiyat Hametim (The Winter of Death) 1881[23]

- Shulamith (Shulamith or The Daughter of Jerusalem) wr. 1880,[21] 1881[24]

- Dos Zenteh Gebot, oder Lo Tachmod (The Tenth Commandment, or Thou Shalt Not Covet) 1882,[24] 1887[21]

- Der Sambatyen (Sambation) 1882[24]

- Doktor Almasada, oder Di Yiden in Palermo (Doctor Almasada, or The Jews of Palermo also known as Doctor Almasado, Doctor Almaraso, Doctor Almasaro) 1880,[21] 1883[24]

- Bar Kokhba, 1883,[21] 1885[24]

- Akeydos Yitschok (The Sacrifice of Isaac), 1891[23]

- Dos Finfteh Gebot, oder Kibed Ov (The Fifth Commandment, or Honor Thy Father), 1892[23]

- Rabi Yoselman, oder Di Gzerot fun Alsas (Rabbi Yoselman, or The Alsatian Decree) 1877,[21] 1892[23]

- Judas Maccabeus, 1892[23]

- Judith and Holofernes, 1892[23]

- Mashiach Tzeiten?! (The Messianic Era?!) 1891[21][22] 1893[23]

- Yiddish translation of Johann Strauss's Gypsy Baron 1894[23]

- Sdom Veamora (Sodom and Gomorrah) 1895[23]

- Di Katastrofe fun Brayla (The Catastrophe in Brăila) 1895[23]

- Meylits Yoysher (The Messenger of Justice) 1897[23]

- David ba-Milchama (David in the War) 1906,[21] in Hebrew

- Ben Ami (Son of My People) 1907,[23] 1908[21]

Songs and poetry

Goldfaden wrote hundreds of songs and poems. Among his most famous are:

- "Der Malekh" ("The Angel")

- "Royzhinkes mit mandlen" (Raisins and Almonds)

- "Shabes, Yontev, un Rosh Khoydesh" ("Sabbath, Festival, and New Moon")

- "Tsu Dayn Geburtstag!" ("To Your Birthday!")

See also

- Yiddish theater

- List of Jewish Romanians

Notes and references

Notes

- Yiddish: אַבֿרהם גאָלדפֿאַדען

- The Romanian spelling Avram Goldfaden is common.

References

- Bercovici, 1998, 118

- Bercovici, 1998, 237-238

- Berkowitz, 2004, 12

- Sandrow, 2003

- Wolitz, Seth L. (August 9, 2010). "Goldfadn, Avrom." YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- "Noted Jewish Bard Dead" (January 10, 1908). The New York Times.

- Bercovici, 1998, 58

- Riff, 1992, 201

- Adler, 1999, 86 (commentary)

- Adler, 1999, 60, 68

- Adler, 1999, 114, 116

- Adler, 1999, 262 commentary

- Bercovici, 1998, 88

- Bercovici, 1998, 88,, 91, 248

- Bercovici, 1998, 89-90 attributes the account to Juvilier, although Sandrow, 2003, 12, tells this as being Leon Blank, not Juvilier

- Sandrow, 2003, 14

- "75,000 At Poet's Burial - East Side Streets Thronged with Mourners for Abraham Goldfaden". The New York Times. January 11, 1908. p. 1. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Sandrow, Nahma. "Goldfadn, Avrom". Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521434379. p. 432.

- "Burial of a Yiddish Poet" (January 12, 1908). The New York Times.

- Berkovitz, 2004, 15-16

- Date according to Partial list of plays by Goldfaden. Many of these may be on the mark, but some (such as the absurdly early 1877 for a serious work such as Rabi Yoselman) are obviously mistaken.

- Date according to [Berkowitz, 2004]

- Date according to [Bercovici, 1998]. Bercovici's dates have been boldfaced where dates are disputed; they may reasonably be seen as authoritative if no earlier date is given, since most are based on specific, cited theater productions.

- Date according to [Sandrow, 2003] as a conservative date (that is, the play is known to have been written by this time).

References

- — "East Side Honors Poet of its Masses; Cooper Union Throng Cheers Eliakum Zunser," The New York Times, March 31, 1905, p. 7.

- —, "Noted Jewish Bard Dead," The New York Times, January 10, 1908, p. 7.

- —, "75,000 at Poet's Funeral," The New York Times, January 11, 1908, p. 1.

- —, "Burial of a Yiddish Poet," The New York Times, January 12, 1908, p. 8.

- —, Partial list of plays by Goldfaden; the names are useful, but some of the dates are certainly incorrect. Retrieved January 11, 2005.

- Adler, Jacob, A Life on the Stage: A Memoir, translated and with commentary by Lulla Rosenfeld, Knopf, New York, 1999, ISBN 0-679-41351-0.

- Bercovici, Israil, O sută de ani de teatru evreiesc în România ("One hundred years of Yiddish/Jewish theater in Romania"), 2nd Romanian-language edition, revised and augmented by Constantin Măciucă. Editura Integral (an imprint of Editurile Universala), Bucharest (1998). ISBN 973-98272-2-5. See the article on the author for further publication information. This is the primary source for the article. Bercovici cites many sources. In particular, the account of the 1873 concert in Odessa is attributed to Archiv far der geşihte dun idişn teater un drame, Vilna-New York, 1930, vol. I, pag. 225.

- Berkowitz, Joel, Avrom Goldfaden and the Modern Yiddish Theater: The Bard of Old Constantine, archived 18 Feb 2006 from the original (PDF), Pakn Treger, no. 44, Winter 2004, 10–19.

- Jacobs, Joseph and Wiernik, Peter, Goldfaden, Abraham B. Hayyim Lippe in the Jewish Encyclopedia (1901–1906). The article is not terribly well researched, but is useful for the names of books, etc.

- Benjamin Nathans, Gabriella Safran (ed),Culture Front - Representing Jews in Eastern Europe, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Michael Riff, The Face of Survival: Jewish Life in Eastern Europe Past and Present. Vallentine Mitchell, London, 1992, ISBN 0-85303-220-3.

- Sandrow, Nahma, "The Father of Yiddish Theater," Zamir, Autumn 2003 (PDF), 9-15. There is much interesting material here, but Sandrow does retail a story about Goldfaden being a poor stage performer, which Bercovici debunks.

- Wolitz, Seth L. (August 9, 2010). "Goldfadn, Avrom." YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abraham Goldfaden. |

- Works by or about Abraham Goldfaden at Internet Archive

- Literature by and about Abraham Goldfaden in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

- Anca Mocanu, Avram Goldfaden şi teatrul ca identitate, Editura Fundaţia Culturală „Camil Petrescu” - revista „Teatrul Azi”, 2012 Avram Goldfaden and Theater as Identity, The Camil Petrescu Cultural Foundation - „Teatrul Azi” magazine Publishing, Romanian Theater Gallery series http://www.fnt.ro/2012/en/Program/Avram-Goldfaden-and-Theater-as-Identity/

- McBee, Richard "Akeydes Yitskhok - Goldfaden's Masterpiece Revived". Archived from the original on 2005-12-19.. The Jewish Press (New York) January 7, 2004: review of a 2003 performance of Goldfaden's operetta Akeydes Yitskhok ("The Sacrifice of Isaac").

- Avraham Levinson - article in Hebrew about Goldfaden on line

- Abraham Goldfaden Collection at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, NY

- Free song lyrics in Yiddish and sheet music by Abraham Goldfaden http://ulrich-greve.eu/free/goldfaden.html