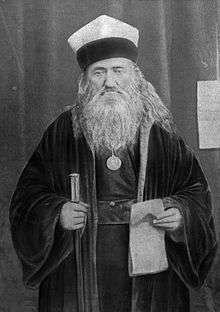

Abraham Firkovich

Abraham (Avraham) ben Samuel Firkovich (Hebrew אברהם בן שמואל - Avraham ben Shmuel; Karayce: Аврагъам Фиркович - Avragham Firkovich) (1786–1874) was a famous Karaite writer and archeologist, collector of ancient manuscripts, and a Karaite Hakham. He was born in Lutsk, Volhynia, then lived in Lithuania, and finally settled in Çufut Qale, Crimea. Gabriel Firkovich of Troki was his son-in-law.

Biography

Abraham Firkovich was born in 1787 into a Crimean Karaite farming family in the Lutsk district of Volhynia, then part of the Russian Empire, now Ukraine. In 1818 he was serving the local Crimean Karaite communities as a junior hazzan, or religious leader, and from there he went on to the city of Eupatoria in Crimea. [1] In 1822, he moved to the Karaite community in Gozleve, and he was appointed as hazan, or community leader, in 1825.[2] Together with the Karaite noble Simha Babovich, he sent memoranda to the Czar, with proposals to relieve Karaites from the heavy taxes imposed on the Jewish community.[3] In 1828 he moved to Berdichev, where he met many Hasidism and learned more about their interpretations of Jewish Scriptures based on the Talmud and rabbinic tradition. The encounter with Rabbinical Jews brought Firkovich into conflict with them. He published a book, "Massah and Meribah" (Yevpatoria, 1838) which argued against the predominant Jewish halakha of the Rabbinites.[4] In 1830 he visited Jerusalem, where he collected many Jewish manuscripts.[5] On his return he remained for two years in Constantinople, as a teacher in the Karaite community there. He then went to Crimea and organized a society to publish old Karaite works, of which several appeared in Yevpatoria (Koslov) with comments by him.[6] In 1838 he was the teacher of the children of Sima Babovich, the head of the Russian Crimean Karaites, who one year later recommended him to Count Vorontzov and to the Historical Society of Odessa as a suitable man to send to collect material for the history of the Crimean Karaites. In 1839, Firkovich began excavations in the ancient cemetery of Çufut Qale, and unearthed many old tombstones, claiming that some of them dated from the first centuries of the common era. The following two years were spent in travels through the Caucasus, where he ransacked the genizot of the old Jewish communities and collected many valuable manuscripts. He went as far as Derbent, and returned in 1842. In later years he made other journeys of the same nature, visiting Egypt and other countries. In Odessa he became the friend of Bezalel Stern and of Simchah Pinsker, and while residing in Wilna he made the acquaintance of Samuel Joseph Fuenn and other Hebrew scholars. In 1871 he visited the small Karaite community in Halych, Galicia, where he introduced several reforms. From there he went to Vienna, where he was introduced to Count Beust and also made the acquaintance of Adolph Jellinek. He returned to pass his last days in Çufut Qale, of which there now remain only a few buildings and many ruins. However, Firkovich's house is still preserved in the site.

Firkovich collected a vast number of Hebrew, Arabic and Samaritan manuscripts during his many travels in his search for evidence concerning the traditions of his people.[7] These included thousands of Jewish documents from throughout the Russian Empire in what became known as the First Firkovich Collection. His Second Collection contains material collected from the Near East. His visit took place about thirty years before Solomon Schechter's more famous trip to Egypt. This "Second Firkovich Collection" contains 13,700 items and is of incredible value.[8]

As a result of his research he became focused on the origin of the ancestors of the Crimean Karaites who he claimed had arrived in Crimea before the common era.[9] The Karaites, therefore, could not be seen as culpable for the crucifixion of Jesus because they had settled in Crimea at such an early date. His theories persuaded the Russian imperial court that Crimean Karaites cannot be accused in Jesus' Crucifixion and they were excluded from the restrictive measures against Jews. Many of his findings were disputed immediately after his death, and despite their important value there is still controversy over many of the documents he collected.[10]

The Russian National Library purchased the Second Firkovich Collection in 1876, a little more than a year after Firkovich's death.[11]

Among the treasures in the Firkovich collection is a manuscript of the Garden of Metaphors, an aesthetic appreciation of Biblical literature written in Judeo-Arabic by one of the greatest of the Sephardi poets, Moses ibn Ezra.[12]

Firkovich's life and works are of great importance to Karaite history and literature. His collections at the Russian National Library are important to biblical scholars and to historians, especially those of the Karaite and Samaritan communities. Controversy continues regarding his alleged discoveries and the reliability of his works.

Works

Firkovich's chief work is his "Abne Zikkaron," containing the texts of inscriptions discovered by him (Wilna, 1872). It is preceded by a lengthy account of his travels to Daghestan, characterized by Strack as a mixture of truth and fiction. His other works are "Ḥotam Toknit," antirabbinical polemics, appended to his edition of the "Mibḥar Yesharim" by Aaron the elder (Koslov, 1835); "Ebel Kabod," on the death of his wife and of his son Jacob (Odessa, 1866); and "Bene Reshef", essays and poems, published by Peretz Smolenskin (Vienna, 1871).

Collections

Abraham Firkovich collected several distinct collections of documents. In sum the Firkovich collection contains approximately 15,000 items; of which many are fragmentary.[13]

The Odessa Collection

This collection contains material from the Crimea and the Caucasus. It was largely collected between 1839 and 1840, but with additions from Firkovich as late as 1852.[14] It was originally owned by the Odessa Society of History and Antiquities and was stored in the Odessa museum.[15][14] Some of these documents deteriorated due to chemical treatment performed by Firkovich. Other documents which were suspected forgeries disappeared; Firkovich claimed they had been stolen.[15] The collection was moved to the Imperial Public Library in 1863.[14]

In 1844 the Russian historian Arist Kunik, a leading anti-Normanist, and Bezalel Stern, an influential Russian Maskil, would study and partly describe the discovery.[15][16]

Briefly stated, the discoveries include the major part of the manuscripts described in Pinner's "Prospectus der Odessaer Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Alterthum Gehörenden Aeltesten Hebräischen und Rabbinischen Manuscripte" (Odessa, 1845), a rather rare work which is briefly described in "Literaturblatt des Orients" for 1847, No. 2. These manuscripts consist of:

- Fifteen scrolls of the Law, with postscripts which give, in Karaite fashion, the date and place of writing, the name of the writer or corrector or other interesting data.

- Twenty copies of books of the Bible other than the Pentateuch, some complete, others fragmentary, of one of which, the Book of Habakkuk, dated 916, a facsimile is given.

- Nine numbers of Talmudical and rabbinical manuscripts.

The First Collection

Contains material from the Crimea and the Caucasus largely collected between 1839 and 1841. It was purchased by the Imperial Public Library in 1862.[17][14]

The Samaritan Collection

Another collection of 317 Samaritan manuscripts, acquired in Nablus, arrived in the St. Petersburg Imperial Academy in 1867 (see Fürst, "Geschichte des Karäerthums", iii. pp. 176, Leipsic, 1869)

In 1864 Firkovich acquired a large collection of Samaritan documents in Nablus. He sold the documents to the Imperial Public Library in 1870. In sum the collection contains 1,350 items.[18]

The Second Collection

Contains material collected from the Near East. The material was collected between 1863 and 1865. Firkovich collected in Jerusalem, Aleppo and also in Cairo.[17] Firkovich concealed where he obtained the documents.[19] He possibly collected from the Cairo Geniza thirty years before Solomon Schechter discovered it.[20] Firkovich sold this collection to the Imperial Public Library in 1873.[17]

Forgery Accusations

Firkovich has come to be regarded as a forger, acting in support of Karaite causes.[21] He wished to eliminate any connection between Rabbinic Judaism and the Karaites by declaring that the Karaites were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes.[22] Firkovich successfully petitioned the Russian government to exempt the Karaites from anti-Jewish laws on the grounds that Karaites had immigrated to Europe before the crucifixion of Jesus and thus could not be held responsible for his death.[23]

S. L. Rapoport has pointed out some impossibilities in the inscriptions (Ha-Meliẓ, 1861, Nos. 13-15, 37); A. Geiger in his Jüdische Zeitschrift (1865, p. 166), Schorr in He-Ḥaluẓ, and A. Neubauer in the Journal Asiatique (1862–63) and in his Aus der Petersburger Bibliothek (Leipzig, 1866) have challenged the correctness of the facts and the theories based upon them which Jost, Julius Fürst, and Heinrich Grätz, in their writings on the Karaites, took from Pinsker's Liḳḳuṭe Ḳadmoniyyot, in which the data furnished by Firkovich were unhesitatingly accepted. Further exposures were made by Strack and Harkavy (St. Petersburg, 1875) in the Catalog der Hebr. Bibelhandschriften der Kaiserlichen Oeffentlichen Bibliothek in St. Petersburg; in Harkavy's Altjüdische Denkmäler aus der Krim (ib. 1876); in Strack's A. Firkowitsch und Seine Entdeckungen (Leipsic, 1876); in Fränkel's Aḥare Reshet le-Baḳḳer (Ha-Shaḥar, vii.646 et seq.); in Deinard's Massa' Ḳrim (Warsaw, 1878); and in other places.

In contradiction, Firkovich's most sympathetic critic, Chwolson, gives as a résumé of his belief, after considering all controversies, that Firkovich succeeded in demonstrating that some of the Jewish tombstones from Chufut-Kale date back to the seventh century, and that seemingly modern forms of eulogy and the method of counting after the era of creation were in vogue among Jews much earlier than had been hitherto suspected. Chwolson alone defended him, but he also was forced to admit that in some cases Firkovich had resorted to forgery. In his Corpus Inscriptionum Hebraicarum (St. Petersburg, 1882; Russian ed., ib. 1884) Chwolson attempts to prove that the Firkovich collection, especially the epitaphs from tombstones, contains much which is genuine.

In 1980, V. V. Lebedev investigated the Firkovich collection and came to the conclusion that forgery cannot be attributed to Firkovich, but rather it was done by the previous owners, in an attempt to increase the price of the manuscripts.[24]

For many years the manuscripts were not available to Western scholars. The extent of Firkovich’s forgeries is still being determined.[25] Firkovich’s materials require careful examination on a case by case basis. His collection remains of great value to scholars of Jewish studies.

See also

- Seraya Shapshal, Philosophical disciple of Firkovich also carrying the Bashyazi Sevel ha Yerushah.

References

- Shapira, Dan DY Shapira. "Firkovich/ Firkowicz".

- https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Firkovich_Avraam_Samuilovich

- https://ibid

- http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/6134-firkovich-abraham-b-samuel-aben-reshef

- https://ibid

- https://ibid

- https://ibid

- Second Firkovich Collection. "Hebrew Manuscripts in the Collections of the National Library of Russia". english.NLR.RU. National Library of Russia.

- https://ibid

- Ben Shammai, Haggai. "Firkovich". Encyclopedia.com. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- http://ibid

- ibid

- Proceedings of the Annual Convention. Association of Jewish Libraries. 1999. p. 143.

- Olga Vasilyeva (2003). "THE FIRKOVICH ODESSA COLLECTION: THE HISTORY OF ITS ACQUISITION AND RESEARCH, PRESENT CONDITION AND HISTORICAL VALUE". Studia Orientalia. 95: 45–53.

- Dan Shapira (2003). Avraham Firkowicz in Istanbul: 1830-1832 : Paving the Way for Turkic Nationalism. Ayse Demiral. pp. 69–70.

- János M. Bak; Patrick J. Geary; Gábor Klaniczay, eds. (2014). Manufacturing a Past for the Present: Forgery and Authenticity in Medievalist Texts and Objects in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Brill. p. 158.

- Miriam Goldstein (2011). Karaite Exegesis in Medieval Jerusalem. Mohr Siebeck. p. 9.

- Tapani Harviainen & Haseeb Shehadeh (2003). "The Acquisition of the Samaritan Collection by Abraham Firkovich in Nablus in 1864 -An Additional Document". Studia Orientalia. 97: 49–63.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Society for Judaeo-Arabic Studies. Congress, Joshua Blau, Stefan C. Reif (1992). Genizah Research After Ninety Years: The Case of Judaeo-Arabic. Cambridge University Press. p. 74.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Stefan C. Reif, Shulamit Reif (2002). The Cambridge Genizah Collections: Their Contents and Significance. Cambridge University Press. p. 63.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Fred Astren (2004). Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 188.

- Jonathan Frankel (1994). Studies in Contemporary Jewry: X: Reshaping the Past: Jewish History and the Historians. OUP USA/Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. p. 33.

- Bernard Dov Weinryb (1973). The Jews of Poland: A Social and Economic History of the Jewish Community in Poland from 1100 to 1800. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 21–22.

- Лебедев В. В. К источниковедческой оценке некоторых рукописей собрания А. С. Фирковича.// Палестинский сборник. — Л., 1987. Вып. 29 (история и филология). — С. 61.)

- David B. Ruderman (2001). Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe. Wayne State University Press. p. 149.

Sources

- Ben-Sasson, M. (1991). "Firkovich's Second Collection: Notes on historical and Halakhic material." Jewish Studies, 31: 47-67 (Hebrew).

- Josephs, Susan. "Fact from Fantasy" The Jewish Week January 12, 2001.

- Markon, I. “Babowitsch, Simcha ben Salamo.” Encyclopaedia Judaica 3: 857-58.

- ________. “Firkowitsch, (Firkowitz), Abraham ben Samuel.” Encyclopaedia Judaica 6: 1017-19.

- Miller, Philip E. Karaite Separatism in Nineteenth-Century Russia. Cincinnati, 1993

- Harkavy, Albert. Altjudische Denkmaller aus der Krim mitgetheilt von Abraham Firkowitsch, 1839-1872. In Memoires de l’Academie Imperiale de St.-Peterboug, VIIe Serie, 24, 1877; reprinted Wiesbaden, 1969.

- Кизилов, Михаил. “Караим Авраам Фиркович: прокладывая путь тюркскому национализму.” Историческое наследие Крыма 9 (2005): 218-221.

- Кизилов М., Щеголева T. Осень караимского патриарха. Авраам Фиркович по описаниям очевидцев и современников // Параллели 2-3 (2003). С.319-362.

- Shapira, Dan. “Remarks on Avraham Firkowicz and the Hebrew Mejelis 'Document'.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 59:2 (2006): 131-180.

- Shapira, Dan. Avraham Firkowicz in Istanbul (1830–1832). Paving the Way for Turkic Nationalism. Ankara: KaraM, 2003.

- Shapira, Dan. “Yitshaq Sangari, Sangarit, Bezalel Stern and Avraham Firkowicz: Notes on Two Forged Inscriptions.” Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 12 (2002–2003): 223-260.

- Kizilov, Mikhail. Karaites through the Travelers’ Eyes. Ethnic History, Traditional Culture and Everyday Life of the Crimean Karaites According to Descriptions of the Travelers. New York: al-Qirqisani, 2003.

- The book “Masa UMriva”, an essay by the Karaite scholar Abraham Samuilovich Firkovich with an explanatory essay to him “Tzedek veShalom” by D-r hazzan Avraam Kefeli, in two volumes (Ashdod 5780, 2019), D.A.N.A. 800-161008

![]()