Sargon of Akkad

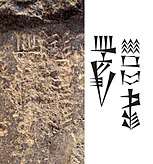

Sargon of Akkad (/ˈsɑːrɡɒn/; Akkadian: 𒊬𒊒𒄀 Šar-ru-gi),[3] also known as Sargon the Great,[4] was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC.[2] He is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire.

| Sargon of Akkad 𒊬𒊒𒄀 | |

|---|---|

| |

Sargon of Akkad on his victory stele, with inscription "King Sargon" (𒊬𒊒𒄀 𒈗 Šar-ru-gi lugal) vertically inscribed in front of him. | |

| King of the Akkadian Empire | |

| Reign | c. 2334–2284 BC (MC)[2] |

| Successor | Rimush |

| Spouse | Tashlultum |

| Issue | Manishtushu, Rimush, Enheduanna, Ibarum, Abaish-Takal |

| Dynasty | Akkadian (Sargonic) |

| Father | La'ibum |

He was the founder of the "Sargonic" or "Old Akkadian" dynasty, which ruled for about a century after his death until the Gutian conquest of Sumer.[5] The Sumerian king list makes him the cup-bearer to king Ur-Zababa of Kish.[6] He is not to be confused with Sargon I, a later king of the Old Assyrian period.[7]

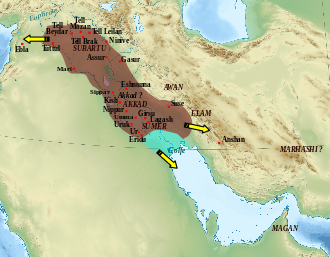

His empire is thought to have included most of Mesopotamia, parts of the Levant, besides incursions into Hurrite and Elamite territory, ruling from his (archaeologically as yet unidentified) capital, Akkad (also Agade).

Sargon appears as a legendary figure in Neo-Assyrian literature of the 8th to 7th centuries BC. Tablets with fragments of a Sargon Birth Legend were found in the Library of Ashurbanipal.[8][9][10]

Name

The Akkadian name is normalized as 𒊬𒊒𒄀 (Šar-ru-gi), or 𒊬𒌝𒄀 (Šar-um-GI).[3] His titulature is "Sargon, king of Akkad", 𒊬𒊒𒄀 𒈗 𒀀𒂵𒉈𒆠 (Šar-ru-gi lugal a-ga-de3ki).[11][12] Later during the 2nd millennium BCE in Old Babylonian tablets relating the legends of Sargon, his name is transcribed as 𒊬𒊒𒌝𒄀𒅔 (Šar-ru-um-ki-in).[13]

The terms "Pre-Sargonic" and "Post-Sargonic" were used in Assyriology based on the chronologies of Nabonidus before the historical existence of Sargon of Akkad was confirmed. The form Šarru-ukīn was known from the Assyrian Sargon Legend discovered in 1867 in Ashurbanipal's library at Nineveh.

A contemporary reference to Sargon thought to have been found on the cylinder seal of Ibni-sharru, a high-ranking official serving under Sargon. Joachim Menant published a description of this seal in 1877, reading the king's name as Shegani-shar-lukh, and did not yet identify it with "Sargon the Elder" (who was identified with the Old Assyrian king Sargon I).[17]

In 1883, the British Museum acquired the "mace-head of Shar-Gani-sharri", a votive gift deposited at the temple of Shamash in Sippar. This "Shar-Gani" was identified with the Sargon of Agade of Assyrian legend.[18] The identification of "Shar-Gani-sharri" with Sargon was recognised as mistaken in the 1910s. Shar-Gani-sharri (Shar-Kali-Sharri) is, in fact, Sargon's great-grandson, the successor of Naram-Sin.[19]

It is not entirely clear whether the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II was directly named for Sargon of Akkad, as there is some uncertainty whether his name should be rendered Šarru-ukīn or as Šarru-kēn(u).[20]

Chronology

Primary sources pertaining to Sargon are sparse; the main near-contemporary reference is that in the various versions of the Sumerian King List. Here, Sargon is mentioned as the son of a gardener, former cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa of Kish. He usurped the kingship from Lugal-zage-si of Uruk and took it to his own city of Akkad. Various copies of the king list give the duration of his reign as either 54, 55 or 56 years.[21] Numerous fragmentary inscriptions relating to Sargon are also known.[22]

In absolute years, his reign would correspond to ca. 2340–2284 BC in the middle chronology.[2] His successors until the Gutian conquest of Sumer are also known as the "Sargonic Dynasty" and their rule as the "Sargonic Period" of Mesopotamian history.[23]

Foster (1982) argued that the reading of 55 years as the duration of Sargon's reign was, in fact, a corruption of an original interpretation of 37 years. An older version of the king list gives Sargon's reign as lasting for 40 years.[24]

Thorkild Jacobsen marked the clause about Sargon's father being a gardener as a lacuna, indicating his uncertainty about its meaning.[25] Ur-Zababa and Lugal-zage-si are both listed as kings, but separated by several additional named rulers of Kish, who seem to have been merely governors or vassals under the Akkadian Empire.[26]

The claim that Sargon was the original founder of Akkad has been called into question with the discovery of an inscription mentioning the place and dated to the first year of Enshakushanna, who almost certainly preceded him.[27] The Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19:51) states that it was Sargon who "built Babylon in front of Akkad."[28][29] The Chronicle of Early Kings (ABC 20:18–19) likewise states that late in his reign, Sargon "dug up the soil of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade."[29][30] Van de Mieroop suggested that those two chronicles may refer to the much later Assyrian king, Sargon II of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, rather than to Sargon of Akkad.[31]

Some of the regnal year names of Sargon are preserved, and throw some light in the events of his reign, particularly the conquest of the surrounding territories of Simurrum, Elam and Mari, and Uru'a, thought to be a city in Elam:[32]

Historiography

Sargon became the subject of legendary narratives describing his rise to power from humble origins and his conquest of Mesopotamia in later Assyrian and Babylonian literature. Apart from these secondary, and partly legendary, accounts, there are many inscriptions due to Sargon himself, although the majority of these are known only from much later copies.[36] The Louvre has fragments of two Sargonic victory steles recovered from Susa (where they were presumably transported from Mesopotamia in the 12th century BC).[37]

Sargon appears to have promoted the use of Semitic (Akkadian) in inscriptions. He frequently calls himself "king of Akkad" first, after the city of Akkad which he apparently founded. He appears to have taken over the rule of Kish at some point, and later also much of Mesopotamia, referring to himself as "Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land [Mesopotamia], governor (ensi) of Enlil".[1][38]

While various copies of the Sumerian king list credit Sargon with a 56, 55, or 54-year reign, dated documents have been found for only four different year-names of his actual reign. The names of these four years describe his campaigns against Elam, Mari, Simurrum (a Hurrian region), and Uru'a (an Elamite city-state).[39]

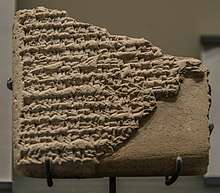

During Sargon's reign, East Semitic was standardized and adapted for use with the cuneiform script previously used in the Sumerian language into what is now known as the "Akkadian language". A style of calligraphy developed in which text on clay tablets and cylinder seals was arranged amidst scenes of mythology and ritual.[40]

Nippur inscription

Among the most important sources for Sargon's reign is a tablet of the Old Babylonian period recovered at Nippur in the University of Pennsylvania expedition in the 1890s. The tablet is a copy of the inscriptions on the pedestal of a Statue erected by Sargon in the temple of Enlil. Its text was edited by Arno Poebel (1909) and Leon Legrain (1926).[44]

Conquest of Sumer

In the inscription, Sargon styles himself "Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer (mashkim) of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed (guda) of Anu, king of the land [Mesopotamia], governor (ensi) of Enlil". It celebrates the conquest of Uruk and the defeat of Lugalzagesi, whom Sargon brought "in a collar to the gate of Enlil":[45]

"Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land, governor of Enlil: he defeated the city of Uruk and tore down its walls, in the battle of Uruk he won, took Lugalzagesi king of Uruk in the course of the battle, and led him in a collar to the gate of Enlil".

Sargon then conquered Ur and E-Ninmar and "laid waste" the territory from Lagash to the sea, and from there went on to conquer and destroy Umma:[47]

"Sargon, king of Agade, was victorious over Ur in battle, conquered the city and destroyed its wall. He conquered Eninmar, destroyed its walls, and conquered its district and Lagash as far as the sea. He washed his weapons in the sea. He was victorious over Umma in battle, [conquered the city, and destroyed its walls]. [To Sargon], lo[rd] of the land the god Enlil [gave no] ri[val]. The god Enlil gave to him [the Upper Sea and] the [Lower (Sea)."

— Inscription of Sargon. E2.1.1.1[47]

Conquest of Upper Mesopotamia, as far as the Mediterranean sea

Submitting himself to the (Levantine god) Dagan, Sargon conquered territories of Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, including Mari, Yarmuti (Jarmuth?) and Ibla "up to the Cedar Forest (the Amanus) and up to the Silver Mountain (Aladagh?)", ruling from the "upper sea" (Mediterranean) to the "lower sea" (Persian Gulf).[48][47]

"Sargon the King bowed down to Dagan in Tuttul. He (Dagan) gave to him (Sargon) the Upper Land: Mari, Iarmuti, and Ebla, as far as the Cedar Forest and the Silver Mountains"

— Nippur inscription of Sargon.[49]

Conquests of Elam and Marhashi

Sargon also claims in his inscriptions that he is "Sargon, king of the world, conqueror of Elam and Parahshum", the two major polities to the east of Sumer.[50] He also names various rulers of the east whom he vanquished, such as "Luh-uh-ish-an, son of Hishibrasini, king of Elam", king of Elam" or " Sidga'u, general of Parahshum", who later also appears in an inscription by Rimush.[50]

Sargon triumphed over 34 cities in total. Ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun, rode at anchor in his capital of Akkad.[51]

He entertained a court or standing army of 5,400 men who "ate bread daily before him".[45]

Sargon Epos

A group of four Babylonian texts, summarized as "Sargon Epos" or Res Gestae Sargonis, shows Sargon as a military commander asking the advice of many subordinates before going on campaigns. The narrative of Sargon, the Conquering Hero, is set at Sargon's court, in a situation of crisis. Sargon addresses his warriors, praising the virtue of heroism, and a lecture by a courtier on the glory achieved by a champion of the army, a narrative relating a campaign of Sargon's into the far land of Uta-raspashtim, including an account of a "darkening of the Sun" and the conquest of the land of Simurrum, and a concluding oration by Sargon listing his conquests.[53]

The narrative of King of Battle relates Sargon's campaign against the Anatolian city of Purushanda in order to protect his merchants. Versions of this narrative in both Hittite and Akkadian have been found. The Hittite version is extant in six fragments, the Akkadian version is known from several manuscripts found at Amarna, Assur, and Nineveh.[54] The narrative is anachronistic, portraying Sargon in a 19th-century milieu.[55] The same text mentions that Sargon crossed the Sea of the West (Mediterranean Sea) and ended up in Kuppara, which some authors have interpreted as the Akkadian word for Keftiu, an ancient locale usually associated with Crete or Cyprus.[56]

Famine and war threatened Sargon's empire during the latter years of his reign. The Chronicle of Early Kings reports that revolts broke out throughout the area under the last years of his overlordship:

Afterward in his [Sargon's] old age all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad; and Sargon went onward to battle and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed. Afterward he attacked the land of Subartu in his might, and they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled that revolt, and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed, and he brought their possessions into Akkad. The soil from the trenches of Babylon he removed, and the boundaries of Akkad he made like those of Babylon. But because of the evil which he had committed, the great lord Marduk was angry, and he destroyed his people by famine. From the rising of the sun unto the setting of the sun they opposed him and gave him no rest.[57]

A. Leo Oppenheim translates the last sentence as "From the East to the West he [i.e. Marduk] alienated (them) from him and inflicted upon (him as punishment) that he could not rest (in his grave)."[58]

Chronicle of Early Kings

Shortly after securing Sumer, Sargon embarked on a series of campaigns to subjugate the entire Fertile Crescent. According to the Chronicle of Early Kings, a later Babylonian historiographical text:

[Sargon] had neither rival nor equal. His splendor, over the lands it diffused. He crossed the sea in the east. In the eleventh year he conquered the western land to its farthest point. He brought it under one authority. He set up his statues there and ferried the west's booty across on barges. He stationed his court officials at intervals of five double hours and ruled in unity the tribes of the lands. He marched to Kazallu and turned Kazallu into a ruin heap, so that there was not even a perch for a bird left.[29]

In the east, Sargon defeated four leaders of Elam, led by the king of Awan. Their cities were sacked; the governors, viceroys, and kings of Susa, Waraḫše, and neighboring districts became vassals of Akkad.[60]

Origin legends

Sumerian legend

The Sumerian-language Sargon legend contains a legendary account of Sargon's rise to power. It is an older version of the previously-known Assyrian legend, discovered in 1974 in Nippur and first edited in 1983.[61]

The extant versions are incomplete, but the surviving fragments name Sargon's father as La'ibum. After a lacuna, the text skips to Ur-Zababa, king of Kish, who awakens after a dream, the contents of which are not revealed on the surviving portion of the tablet. For unknown reasons, Ur-Zababa appoints Sargon as his cup-bearer. Soon after this, Ur-Zababa invites Sargon to his chambers to discuss a dream of Sargon's, involving the favor of the goddess Inanna and the drowning of Ur-Zababa by the goddess. Deeply frightened, Ur-Zababa orders Sargon murdered by the hands of Beliš-tikal, the chief smith, but Inanna prevents it, demanding that Sargon stop at the gates because of his being "polluted with blood." When Sargon returns to Ur-Zababa, the king becomes frightened again and decides to send Sargon to king Lugal-zage-si of Uruk with a message on a clay tablet asking him to slay Sargon.[62] The legend breaks off at this point; presumably, the missing sections described how Sargon becomes king.[63]

The part of the interpretation of the king's dream has parallels to the biblical story of Joseph, the part about the letter with the carrier's death sentence has similarities to the Greek story of Bellerophon and the biblical story of Uriah.[64]

Birth legend

.jpg)

A Neo-Assyrian text from the 7th century BC purporting to be Sargon's autobiography asserts that the great king was the illegitimate son of a priestess. Only the beginning of the text (the first two columns) is known, from the fragments of three manuscripts. The first fragments were discovered as early as 1850.[65] Sargon's birth and his early childhood are described thus:

My mother was a high priestess, my father I knew not. The brothers of my father loved the hills. My city is Azupiranu, which is situated on the banks of the Euphrates. My high priestess mother conceived me, in secret she bore me. She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen she sealed my lid. She cast me into the river which rose over me. The river bore me up and carried me to Akki, the drawer of water. Akki, the drawer of water, took me as his son and reared me. Akki, the drawer of water, appointed me as his gardener. While I was a gardener, Ishtar granted me her love, and for four and ... years I exercised kingship.

Similarities between the Sargon Birth Legend and other infant birth exposures in ancient literature, including Moses, Karna, and Oedipus, were noted by psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909.[66] The legend was also studied in detail by Brian Lewis, and compared with many different examples of the infant birth exposure motif found in European and Asian folktales. He discusses a possible archetype form, giving particular attention to the Sargon legend and the account of the birth of Moses.[8] Joseph Campbell has also made such comparisons.[67]

Sargon is also one of the many suggestions for the identity or inspiration for the biblical Nimrod. Ewing William (1910) suggested Sargon based on his unification of the Babylonians and the Neo-Assyrian birth legend.[68] Yigal Levin (2002) suggested that Nimrod was a recollection of Sargon and his grandson Naram-Sin, with the name "Nimrod" derived from the latter.[69]

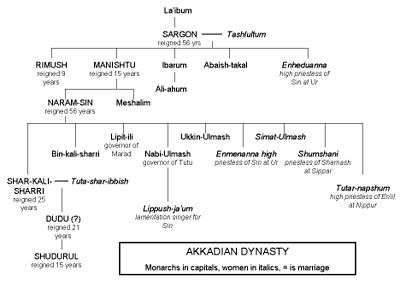

Family

The name of Sargon's main wife, Queen Tashlultum,[70] and those of a number of his children are known to us. His daughter Enheduanna was a priestess who composed ritual hymns.[71] Many of her works, including her Exaltation of Inanna, were in use for centuries thereafter.[72] Sargon was succeeded by his son Rimush; after Rimush's death another son, Manishtushu, became king. Manishtushu would be succeeded by his own son, Naram-Sin. Two other sons, Shu-Enlil (Ibarum) and Ilaba'is-takal (Abaish-Takal), are known.[73]

Legacy

Sargon of Akkad is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire (in the sense of the central government of a multi-ethnic territory),[75][76][77] although earlier Sumerian rulers such as Lugal-zage-si might have a similar claim.[78] His rule also heralds the history of Semitic empires in the Ancient Near East, which, following the Neo-Sumerian interruption (21st/20th centuries BC), lasted for close to fifteen centuries until the Achaemenid conquest following the 539 BC Battle of Opis.[79]

Sargon was regarded as a model by Mesopotamian kings for some two millennia after his death. The Assyrian and Babylonian kings who based their empires in Mesopotamia saw themselves as the heirs of Sargon's empire. Sargon may indeed have introduced the notion of "empire" as understood in the later Assyrian period; the Neo-Assyrian Sargon Text, written in the first person, has Sargon challenging later rulers to "govern the black-headed people" (i.e. the indigenous population of Mesopotamia) as he did.[80] An important source for "Sargonic heroes" in oral tradition in the later Bronze Age is a Middle Hittite (15th century BC) record of a Hurro-Hittite song, which calls upon Sargon and his immediate successors as "deified kings" (dšarrena).[81]

Sargon shared his name with two later Mesopotamian kings. Sargon I was a king of the Old Assyrian period presumably named after Sargon of Akkad. Sargon II was a Neo-Assyrian king named after Sargon of Akkad; it is this king whose name was rendered Sargon (סַרְגוֹן) in the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah 20:1).

Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus showed great interest in the history of the Sargonid dynasty and even conducted excavations of Sargon's palaces and those of his successors.[82]

Popular culture

Although historically inaccurate and supernatural in nature, The Scorpion King: Rise of a Warrior (2008) features Sargon of Akkad as a murderous army commander who uses black magic. He was the film's main villain and was portrayed by American actor and mixed martial artist Randy Couture.[83] This is one of the few films, if not the only one, to depict Sargon.

The twentieth episode of the second season of Star Trek the original series, Return to Tomorrow, features an ancient, telepathic alien named Sargon who once ruled a mighty empire.

.jpg)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sargon of Akkad. |

Notes

- "King of Akkad, Kish, and Sumer" is a translation of the Akkadian phrase "LUGAL Ag-ga-dèKI, LUGAL KIŠ, LUGAL KALAM.MAKI". See Peter Panitschek, Lugal - šarru - βασιλεύς: Formen der Monarchie im Alten Vorderasien von der Uruk-Zeik bis zum Hellenismus (2008), p. 138. KALAM.MA, meaning "land, country", is the old Sumerian name of the cultivated part of Mesopotamia (Sumer). See Esther Flückiger-Hawker, Urnamma of Ur in Sumerian Literary Tradition (1999), p. 138.

- The date of the reign of Sargon is highly uncertain, depending entirely on the (conflicting) regnal years given in the various copies of the Sumerian King List, specifically the uncertain duration of the Gutian dynasty. The added regnal years of the Sargonic and the Gutian dynasties have to be subtracted from the accession of Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which is variously dated to either 2047 BC (Short Chronology) or 2112 BC (Middle Chronology). An accession date of Sargon of 2334 BC assumes: (1) a Sargonic dynasty of 180 years (fall of Akkad 2154 BC), (2) a Gutian interregnum of 42 years and (3) the Middle Chronology accession year of Ur-Nammu (2112 BC).

- "Sargon inscriptions". cdli.ucla.edu.

- also "Sargon the Elder", and in older literature Shargani-shar-ali and Shargina-Sharrukin. Gaston Maspero (ed. A. H. Sayce, trans. M. L. McClure), History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria (1906?), p. 90.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000–323 BC. Blackwell, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-4911-2. p. 63.

- Bauer, Susan Wise (17 March 2007). The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome - Susan Wise Bauer - Google Książki. ISBN 9780393070897.

- Bromiley 1996

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (January 1984). "Review of The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth. By Brian Lewis". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 43 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1086/373065. JSTOR 545065.

- Brian Edric Colless. "The Empire of Sargon". Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- King, L. W. (1907). Chronicles concerning early Babylonian kings. London, Luzac and co. pp. 87–96.

- "CDLI-Sargon Archives". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Cooper, Jerrold S.; Heimpel, Wolfgang (1983). "The Sumerian Sargon Legend". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 103 (1): 67–82. doi:10.2307/601860. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 601860.

- "Victory stele of Sargon". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Foster, Benjamin R. (2015). The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 9781317415527.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 93–94. doi:10.2307/4200454. JSTOR 4200454.

- Louis de Clercq, Catalogue méthodique et raisonné. Antiquités assyriennes, cylindres orientaux, cachets, briques, bronzes, bas-reliefs, etc., vol. I, Cylindres orientaux, avec la collaboration de Joachim Menant, E. Leroux, Paris, 1888, no. 46.

- Leonard William King, A History of Sumer and Akkad (1910), 216–218.

- "But it is now evident that Sharganisharri was 'not confused with Shargani or Sargon' in the 'tradition' (p. 133), but only by the moderns who insisted on connecting the Sharganisharri of contemporary documents with the Sargon of the Legend" D. D. Luckenbill, Review of: The Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria by Morris Jastrow, Jr., The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures Vol. 33, No. 3 (Apr. 1917), pp. 252-254.

- References to Sargon II are mostly spelled logographically, as LUGAL-GI.NA or LUGAL-GIN, but occasional phonetic spelling in ''ú-kin appears to support the form Šarru-ukīn over Šarru-kēn(u) (based on a single spelling in -ke-e-nu found in Khorsabad). The name of the Old Assyrian king Sargon I is spelled as LUGAL-ke-en or LUGAL-ki-in in king lists. In addition to the Biblical form (סרגון), the Hebrew spelling סרגן has been found in an inscription in Khorsabad, suggesting that the name in the Neo-Assyrian period might have been pronounced Sar(ru)gīn, the voicing representing a regular development in Neo-Assyrian. (Frahm 2005)

- 266-296: "In Agade, Sargon, whose father was a gardener, the cupbearer of Ur-Zababa, became king, the king of Agade, {who built Agade} {L1+N1: under whom Agade was built}; he ruled for {WB:56; L1+N1: 55; TL: 54} years. Rīmuš, the son of Sargon, ruled for {WB: 9} {IB: 7, L1+N1: 15} years. Man-ištiššu, the older brother of Rīmuš, the son of Sargon, ruled for {WB: 15} {L1+N1: 7} years. Narām-Suen, the son of Man-ištiššu, ruled for {L1+N1, P3+BT14: 56} years. Šar-kali-šarrī, the son of Narām-Suen, ruled for {L1+N1, Su+Su4: 25; P3+BT14: 24} years. {P3+BT14: 157 are the years of the dynasty of Sargon.}" mss. are referred to by the sigla used by Vincente 1995. Electronic Text Corpus of the Sumerian Language

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Mari A. Gough, "Historical Perception in the Sargonic Literary Tradition: the Implications of Copied Texts" , Rosetta 1 (2006), 1–9. Douglas R. Frayne, "The Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334-2113)", University of Toronto Press, 1993.

- Rebecca Hasselbach, Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts (2005), p. 5 (fn 28).

- Jacobsen 1939: 111

- "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Kish / Kic". www.historyfiles.co.uk.

- Van de Mieroop 1999: 74–75

- Grayson 1975: 19:51

- Chronicle of Early Kings at Livius.org. Translation adapted from Grayson 1975 and Glassner 2004

- Grayson 1975: 20:18–19

- Stephanie Dalley, Babylon as a Name for Other Cities Including Nineveh, in Proceedings of the 51st Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Oriental Institute SAOC 62, pp. 25–33, 2005

- Potts, D. T. (2016). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-107-09469-7.

- "Year Names of Sargon". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Basello, Gian Pietro; Wicks, Yasmina (2018). The Elamite World. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-317-32983-1.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 92. doi:10.2307/4200454. JSTOR 4200454.

- Gwendolyn Leick, Who's Who in the Ancient Near East, Routledge (2002), p. 141.

- Lorenzo Nigro, "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief" Iraq LX (1998); Louvre Sb1 (Stèle de victoire de Sargon, roi d'Akkad, Apportée à Suse, Iran, en butin de guerre au XIIe siècle avant J.-C. Fouilles J. de Morgan).

- Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, BRILL (2003), p. 106.

- "T2K1.htm". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Britannica

- Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780521564960.

- McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 235. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 85–102. doi:10.2307/4200454. JSTOR 4200454.

- Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, University of Chicago Press (1963), 59f

- Mario Liverani, The Ancient Near East: History, Routledge (2013), p. 143. Kramer 1963 p. 324. Kuhrt, Amélie, The Ancient Near East: C.3000-330 B.C., Routledge 1996 ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5, p. 49

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- Frayne, Douglas. Sargonic and Gutian Periods. pp. 10–12.

- A.H.Sayce, review of G. Contenau, Les Tablettes de Kerkouk (1926), Antiquity 1.4 (December 1927), 503f. "Yarmuti is probably the Yarimuta of the Tel el-Amarna letters, the name of which seems to be preserved in that of Armuthia south of Killiz. [...] the Silver mountains must be the Ala-Dagh, where at Bereketli Maden there are extensive remains of ancient silver mines"; c.f. W.F. Albright, "The Origin of the Name Cilicia", American Journal of Philology 43.2 (1922), 166f. "Another, much more portentous mistake of the same kind (loc. cit. [ Jour. Eg. Arch., VI, 296]) is Sayce's statement that Yarmuti is "classical" Armuthia. The source of this is Tompkins, Trans. Soc. Bib. Arch., IX, 242, ad 218 (of the Tuthmosis list): "Mauti. Perhaps the Yari-muta of the Tel el‑Amarna tablets, now (I think) Armūthia, south of Killis." This is the modern village of Armûdja, a hamlet some three miles south of Killis, not on the coast at all, but in the heart of Syria, and with no known classical background." See also M. C. Astour in Eblaitica vol. 4, Eisenbrauns (1987), 68f.

- Buck, Mary E. (2019). The Amorite Dynasty of Ugarit: Historical Implications of Linguistic and Archaeological Parallels. BRILL. p. 169. ISBN 978-90-04-41511-9.

- Frayne, Douglas. Sargonic and Gutian Periods. p. 22.

- "MS 2814 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts Eisenbrauns, 1997, p. 59.

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts Eisenbrauns, 1997, p. 102.

- Studevent-Hickman, Benjamin; Morgan, Christopher (2006). "Old Akkadian Period Texts". In Chavalas, Mark William (ed.). The ancient Near East: historical sources in translation. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0-631-23580-4.

- Wainright, G.A. "Asiatic Keftiu." American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 56, No. 4 (October 1952), pp. 196–212; Strange, John. "Caphtor/Keftiu: A New Investigation." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 102, No. 2 (April–June 1982), pp. 395–396; Vandersleyen, Claude. "Keftiu: A Cautionary Note." Oxford Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 22 Issue 2 Page 209 (2003).

- Botsforth 1912: 27–28

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (translator). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3d ed. James B. Pritchard, ed. Princeton: University Press, 1969, p. 266.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 85–102. doi:10.2307/4200454. JSTOR 4200454.

- Gershevitch, I. (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Cooper, J.S., and Heimpel, W., "The Sumerian Sargon Legend", Journal of the American Oriental Society 103 (1983), 67-82. Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts (1997), p. 12.

- "The Sargon Legend." The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University, 2006

- Cooper & Heimpel 1983: 67–82

- Cynthia C. Polsley, "Views of Epic Transmission in Sargonic Tradition and the Bellerophon Saga" (2012). Bendt Alster, "A Note on the Uriah Letter in the Sumerian Sargon Legend", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 77.2 (1987). Stephanie Dalley, Sargon of Agade in literature: "The episode of dreams which Joseph interpreted for Pharaoh in Genesis 37 bears a notable resemblance to Sargon’s interpretation of the dreams of the king of Kish in the Sumerian Legend of Sargon, the same legend contains the motif of the messenger who carries a letter which orders his own death, comparable to the story of Uriah in 2 Samuel 11 (and of Bellerophon in Iliad 6). The episode in the Akkadian Legend of Sargon’s Birth, in which Sargon as an infant was concealed and abandoned in a boat, resembles the story of the baby Moses in Exodus 2. The Sumerian story was popular in the early second millennium, and the Akkadian legend may originally have introduced it. Cuneiform scribes were trained with such works for many centuries. They enjoyed new popularity in the late eighth century when Sargon II of Assyria sought to associate himself with his famous namesake."

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Legends of the Kings of Akkade: The Texts (1997), 33–49.

- Otto Rank (1914). The myth of the birth of the hero: a psychological interpretation of mythology. English translation by Drs. F. Robbins and Smith Ely Jelliffe. New York : The Journal of nervous and mental disease publishing company.

- Campbell, Joseph (1964). The Masks of God, Vol. 3: Occidental Mythology. p. 127.

- Ewing, William (1910). The Temple Dictionary of the Bible. London, J.M. Dent & sons ; New York, E.P. Dutton. p. 514.

- Levin, Yigal (2002). "Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad". Vetus Testamentum. 52 (3): 350–356. doi:10.1163/156853302760197494.

- Tetlow, Elisabeth Meier (2004). Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5. Retrieved 29 July 2011. Michael Roaf (1992). Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East. Stonehenge Press. ISBN 978-0-86706-681-4. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Schomp 2005: 81

- Schomp 2005: 81; Kramer 1981: 351; Hallo, W. and J. J. A. Van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

- Frayne 1993: 3637

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Rattini, Kristin Baird (18 June 2019). "Meet the world's first emperor".

- Ersek, Vasile (7 January 2019). "How Did the World's First Empire Collapse?". RealClearScience.

- Vitkus, Saul N. (September 1976). "Sargon Unseated". The Biblical Archaeologist. 39 (3): 114–117. doi:10.2307/3209401. JSTOR 3209401.

- Postgate, J. N. (February 1994). "In Search of the First Empires". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 293 (293): 1–6. doi:10.2307/1357273. JSTOR 1357273.

- Sargon is the earliest known ruler with a Semitic name for whom anything approaching a historical context is recorded. There are, however, older references to rulers bearing Semitic names, notably the pre-Sargonic king Meskiang-nunna of Ur by his queen Gan-saman, mentioned in an inscription on a bowl found at Ur. In addition, the names of some pre-Sargonic rulers of Kish in the Sumerian king list have been interpreted as having Semitic etymologies, which might extend the Semitic presence in the Near East to the 29th or 30th century. See J. N. Postgate, Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. British School of Archaeology in Iraq (2007).

- "The black-headed peoples I ruled, I governed; mighty mountains with axes of bronze I destroyed. I ascended the upper mountains; I burst through the lower mountains. The country of the sea I besieged three times; Dilmun I captured. Unto the great Dur-ilu I went up, I ... I altered ... Whatsoever king shall be exalted after me, ... Let him rule, let him govern the black-headed peoples; mighty mountains with axes of bronze let him destroy; let him ascend the upper mountains, let him break through the lower mountains; the country of the sea let him besiege three times; Dilmun let him capture; To great Dur-ilu let him go up." Barton 310, as modernized by J. S. Arkenberg

- Bachvarova (2016:182).

- Oates, John. Babylon. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979, p.162.

- "The Scorpion King 2: Rise of a Warrior synopsis". The Scorpion King. Archived from the original on 3 September 2004. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 237. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

References

- Albright, W. F., A Babylonian Geographical Treatise on Sargon of Akkad's Empire, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1925).

- Bachvarova, Mary R., "Sargon the Great: from history to myth", chapter 8 in: From Hittite to Homer: The Anatolian Background of Ancient Greek Epic' , Cambridge University Press (2016), 166–198.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain, et al. A Companion to the Ancient near East. Blackwell, 2005.

- Botsforth, George W., ed. "The Reign of Sargon". A Source-Book of Ancient History. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. and Wolfgang Heimpel. "The Sumerian Sargon Legend." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 103, No. 1, (January–March 1983).

- Foster, Benjamin R., The Age of Akkad. Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia, Routledge, 2016.

- Frayne, Douglas R. "Sargonic and Gutian Period." The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 2. University of Toronto Press, 1993.

- Gadd, C.J. "The Dynasty of Agade and the Gutian Invasion." Cambridge Ancient History, rev. ed., vol. 1, ch. 19. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1963.

- Glassner, Jean-Jacques. Mesopotamian Chronicles, Atlanta, 2004.

- Grayson, Albert Kirk. Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. J. J. Augustin, 1975; Eisenbrauns, 2000.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild, The Sumerian King List, Assyriological Studies, No. 11, Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1939.

- King, L. W., Chronicles Concerning Early Babylonian Kings, II, London, 1907, pp. 87–96.

- Kramer, S. Noah. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character, Chicago, 1963.

- Kramer, S. Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine "Firsts" in Recorded History. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

- Lewis, Brian. The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series, No. 4. Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1984.

- Luckenbill, D. D., On the Opening Lines of the Legend of Sargon, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures (1917).

- Postgate, Nicholas. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge, 1994.

- Roux, G. Ancient Iraq, London, 1980.

- Sallaberger, Walther; Westenholz, Aage (1999), Mesopotamien. Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 160/3, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, ISBN 978-3-525-53325-3

- Schomp, Virginia. Ancient Mesopotamia. Franklin Watts, 2005. ISBN 0-531-16741-0

- Van de Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000–323 BC. Blackwell, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-4911-2.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc., Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History, Routledge, 1999.

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ur-Zababa |

King of Kish ? – 2284 BC (middle) |

Succeeded by Rimush |

| Preceded by Lugal-Zage-Si |

King of Uruk, Lagash, and Umma ca. 2340–2284 BC (middle) | |

| New title | King of Akkad ca. 2340–2284 BC (middle) | |

| Preceded by Luh-ishan of Awan |

Overlord of Elam ca. 2340–2284 BC (middle) | |

_on_his_victory_stele.jpg)

.jpg)