A Slave of Love

A Slave of Love (Russian: Раба любви, romanized: Raba lyubvi) is a 1976 Soviet romantic comedy-drama film directed by Nikita Mikhalkov and written by Friedrich Gorenstein and Andrey Konchalovskiy. It stars Elena Solovey, Rodion Nakhapetov and Aleksandr Kalyagin. The film is about a silent film actress Olga Voznesenskaya (Elena Solovey), whose films are so admired by the revolutionaries that they risk capture to see her on the screen. The character of Olga was inspired by Vera Kholodnaya.[1]

| A Slave of Love | |

|---|---|

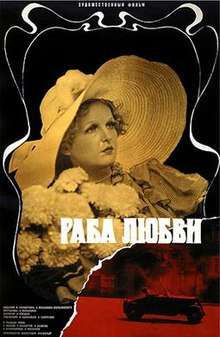

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Nikita Mikhalkov |

| Written by | Fridrikh Gorenshteyn, Andrey Konchalovskiy |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Eduard Artemyev |

| Cinematography | Pavel Lebeshev |

| Edited by | Lyudmila Yelyan |

| Distributed by | Mosfilm |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

Plot

The film is set in the Autumn/Fall of 1918, during the Russian Civil War.

The silent movie star, Olga Voznesenskaya, has just celebrated a triumph, along with her co-star and lover, Vladimir Maksakov, in the romantic comedy "Slave of Love". The Bolsheviks have captured Moscow, and the film team moves south, to Odessa, in order to work on a new production away from the fighting. Olga is a difficult star, sometimes overwrought, sometimes deeply wrapped up in her own stardom. Maksakov does not accompany the others to Odessa, which means that filming must be halted. Olga has in any case refused to appear without her partner, and the remaining stocks of unused film have become spoiled. On the set Olga gets to know the camera operator, Viktor Potozki, and soon falls for him. Additionally Fedotov, the local spy chief of the "White Guard" (an important anti-Bolshevik force in the all too real Civil War of the time), appears on the film set with increasing frequency, while Bolsheviks are being arrested across the land.

After a short while, more actors and support personnel turn up from Moscow, bringing with them fresh supplies so that filming can resume. Maksakov is not with them, however, and his role is recast. The taste of audiences for silent movies has moved on, and there is a requirement for exotic embellishments which Voznesenskaya, like her absent partner Maksakov, rejects as artistically counter-productive. But when Voznesenskaya over-reacts and runs off to a cinema, announcing that the film they are making is a lie, she is showered with flowers by her fans, which mollifies her a little.

One day the camera operator Viktor Potozki arrives on set late, and apparently drunk. Filming is interrupted by the intervention of the White Russian spy chief Fedotov. Fedotov is searching all the film teams in Odessa to try to find a camera operator who a little time earlier had filmed, secretly, the death by shooting of a revolutionary. Vikor, who in reality is completely sober, admits to Olga that he is the camera operator that Fedotov is looking for. Potozki had used the supposedly spoiled film stock to film White Guard atrocities in order to promote the Bolshevik cause. "In Europe they publicise Bolshevik atrocities", he says, "but they should look at this!" The film footage in question is in Potozki's car. Olga successfully rescues it, and is exhilarated by the realisation that she has, by this action, saved Viktor's life. Soon afterwards, at Viktor's invitation, she is given a secret screening of the footage. He shows her shootings of insurgents following denunciations, the hunger of the refugees and the suffering of those left behind. Olga is shattered, and now refuses to continue with her own work on the film-set.

A theme of the film is the interface between the apolitical Olga and the film team, and the passionate political commitment represented by the camera operator Potozki. As Potozki's true priorities emerge little by little, two powerful sets of emotions begin to overlap, with Olga's exclamation, "My God, what a beautiful thing it is to take part in a cause for which you might die or end up in prison!" Olga appears to have fallen in love with Potozki, with whom she meets up in a cafe so that he can hand over the secret film roll for her to keep safely till the evening. However, as they leave the cafe Potozki is shot dead by Fedotov's men.

Olga now tries to pass the film roll across to Potozki's fellow Bolshevik partisans, but they appear to know nothing about it. That evening the White Russian spy, Fedotov, again turns up on the film-set, where the production team are trying to get the by now thoroughly apathetic Olga to finish the climactic suicide scene in their movie. Suddenly Potozki's comrades arrive. They shoot Fedotov and his men, and rush off, taking Olga and the film roll with them. They place Olga in a tram and force the driver to take her to her hotel in the city centre. However, during the journey the driver jumps off and alerts the White Guard that there is revolutionary on the tram. The guards leap onto their horses and pursue the tram, from which Olga curses them as "beasts". The tram and its pursuers disappear into the fog.

The final few moments of the film were rewritten for ideological reasons. In the original version Olga, facing her Bolshevik pursuers from the back of the tram, can be seen mouthing to them "I'm not with them: I'm on your side". It was only at the last minute that this section was reshot, with Olga, no longer inaudible, yelling "Beasts!" at the horsemen.

Cast

- Elena Solovey as Olga Nikolayevna Voznesenskaya

- Rodion Nakhapetov as Victor Pototsky

- Aleksandr Kalyagin as Kalyagin

- Oleg Basilashvili as Yuzhakov

- Konstantin Grigorev as Fedotov

- Yuri Bogatyryov as Maksakov

Background and production

Vera Kholodnaya, sometimes described as Russia's first major movie star was the inspiration for the character of Olga Voznesenskaya. She died in Odessa in 1919 from influenza in her mid twenties. Kholodnaya was rumoured to have worked as a Bolshevik spy towards the end of her life.[2] In 1972 the Soviet director Rustam Khamdamov started to make a biographical film about Kholodnaya, under the title "Нечаянные радости" ("Inadvertent Pleasures"); but the production was interrupted and the project was never completed. Some of the costumes created for Khamdamov's film were then used in A Slave of Love. Additionally, Elena Solovey, who stars as Olga in A Slave of Love, had previously been the actress picked for the starring role in Khamdamov's uncompleted movie.

Most of the film is produced in conventional full colour. However, the "secret film" produced by Viktor of White Guard atrocities, included when he screens it for Olga, uses monochrome: these sections are indeed interspliced with contemporary Russian Civil War footage. In addition, scenes from the silent movie featuring Olga sometimes appear in the background in "black and white".

Themes and influence

Birgit Beumers, the author of Nikita Mikhalkov: The Filmmaker's Companion, believes that in the film, Mikhalkov offers an idealised view of the revolution, not based on reality,[3] in that he treats revolution and love as synonyms. She writes: "the sexual seduction in the old world is replaced by political seduction accomplished by Viktor to bring Olga to the side of the Revolution; Olga's suicide in the film of the old world is substituted by the surrender of her life to the ideal of Bolshevism: she saves Viktor's film, and travels herself towards a new life". [4] Aside from issuing a "subtle comment on the nature of film", with a "false, artificial, trite" screen reality, for Beumers, Olga is "rendered as a type in a melodrama", who is unable to see reality, and distracts herself from political reality through cinema.

Beumers highlights the way Mikhalkov appears to mock the film crew in the film, with the obesity of director Kalyagin, producer Yuzhakov's concern about the arrival of film stock, scriptwriter Konstantinovich's writer's block, and actress Olga's image fears.[5] Beumers likens one of the scenes to the three frames of the statue of the lion in Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin.[6] Beumers also notes Mikhalkov's effective use of black and white inserts, including the silent film footage itself, and Viktor's documentary footage, which she believes represent history, contrasting it with the present in colour.[4]

Nancy Condee notes, that by combining revolutionary message with melodramatic mode of expression, Mikhalkov is able to "gesture at a space beyond Marxism-Leninism while at the same time in no sense opposing or negating it".[7] Writing about A Slave of Love, Condee re-purposes Christine Gledhill's characterization of melodrama, "if realism's relentless search for renewed truth and authentication pushes it towards the future, melodrama's search for something lost, inadmissible, repressed, ties it to an atavistic past".[7]

Release and reception

A Slave of Love premiered in Soviet cinemas on 27 September 1976. In the near abroad, it appeared in cinemas in the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) on 21 January 1977. It was first transmitted on East German television on 21 July 1977. Meanwhile, in the German Federal Republic (West Germany) cinema screenings began on 2 July 1987. West German television audiences had their first opportunity to see the movie only on 28 February 1996, long after reunification, when it was screened on the Franco-German Arte channel. In 2005 Icestorm came out with a DVD of A Slave of Love, as part of their "Russian Classics" series.

Critically acclaimed, Mikhalkov won Best Director at the Tehran International Film Festival in 1976.[8] In 1978 the film was voted one of the best foreign films by the National Board of Review, and was voted the 3rd best foreign film of the year at both the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards and New York Film Critics Circle Awards. The New York Times called it an "unexpected masterpiece", while Jack Nicholson and director Monte Hellman praised it highly.[1]

References

- "A Slave of Love". kinolorber.com. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "ХОЛОДНАЯ Вера Васильевна (в девичестве – Левченко)" (in Russian). "Russian Actors" website. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Beumers 2005, p. 38.

- Beumers 2005, p. 36.

- Beumers 2005, p. 32.

- Beumers 2005, p. 33.

- Condee 2009, p. 97.

- Beumers 2005, p. 37.

- Sources

- Beumers, Birgit (5 February 2005). Nikita Mikhalkov: The Filmmaker's Companion 1. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-785-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Condee, Nancy (2009). The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199710546.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)