A Bird came down the Walk

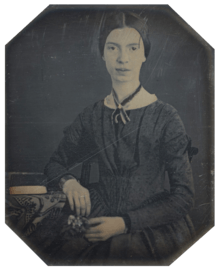

"A Bird came down the Walk" is a short poem by Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) that tells of the poet's encounter with a worm-eating bird. The poem was first published in 1891 in the second collection of Dickinson's poems.

Summary

The poet encounters a bird on the walk who eats an angle-worm, drinks a dew from a convenient grass, and then steps aside to let a beetle pass. The bird then glances about, apparently frightened. The poet offers the bird a crumb but the bird takes flight. In this poem Dickinson watched the bird when it came down to the walk. The bird didn't know the poetess was watching it. It caught the angle-worm and it pecked it into two parts. Then it ate the raw flesh of the worm and drank a drop of dew from a nearby grass. Then the bird looks around quickly with its darting eyes in order to protect it from other evil forces. Then the narrator offers the bird a piece of crumb, but the bird neglects it and then it flies away. The poet observes that the flight of the bird is "softer" than moving the oars that divide the ocean or that of butterflies plunging soundlessly into space . The bird and its actions are captured in minute details in the poem, through vivid images.

Text

Close transcription[1] First published version[2]

A Bird, came down the Walk -

He did not know I saw -

He bit an Angle Worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw,

And then, he drank a Dew

From a convenient Grass -

And then hopped sidewise to the Wall

To let a Beetle pass -

He glanced with rapid eyes,

That hurried all abroad -

They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,

He stirred his Velvet Head. -

Like one in danger, Cautious,

I offered him a Crumb,

And he unrolled his feathers,

And rowed him softer Home -

Than Oars divide the Ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or Butterflies, off Banks of Noon,

Leap, plashless as they swim.IN THE GARDEN

A bird came down the walk:

He did not know I saw;

He bit an angle-worm in halves

And ate the fellow, raw.

And then, he drank a dew

From a convenient grass,

And then hopped sidewise to the wall

To let a beetle pass.

He glanced with rapid eyes

That hurried all abroad,—

They looked like frightened beads, I thought;

He stirred his velvet head

Like one in danger; cautious,

I offered him a crumb,

And he unrolled his feathers

And rowed him softer home

Than oars divide the ocean,

Too silver for a seam,

Or butterflies, off banks of noon,

Leap, plashless, as they swim.

Critique

Helen Vendler regards the poem as a "bizarre little narrative" but one that typifies many of Dickinson's best qualities. She likens the poet to a reporter observing a murderer in the act, and later, pretending fear that the murderer may be dangerous to herself and must be mollified by a "crumb". The bird takes flight and Vendler regards what follows - the description of the bird in flight - as "the astonishing part of the poem". Vendler notes that the poem typifies Dickinson's "cool eye, her unsparing factuality, her startling similes and metaphors, her psychological observations of herself and others, her capacity for showing herself mistaken, and her exquisite relish of natural beauty".[3]

Harold Bloom notes that the bird displays a "complex mix of qualities: ferocity, fastidiousness, courtesy, fear, and grace", and writes that the description of the bird's flight is that seen by the soul rather than the "finite eyes".[4]

Vendler observes that Dickinson wrote two versions of the middle portion of the poem. The version she sent to her literary mentor Thomas Wentworth Higginson has no punctuation after "Head" and a period after the word "Cautious". In Dickinson's personal copy, there is a comma (not a period) after "Cautious". In the first version then, the bird is cautious, but in the second version, it is the poet who is cautious. In the fair copy, both a period and a dash follow "Head", and a comma follows "Cautious". The fair copy version is the one usually printed, and, as Vendler notes, this version accords with Dickinson's comic sense.[3] Dr. Chuck Taylor, poet and professor, believes this naturalistic description of a bird to be also symbolic. The description of the bird taking flight lightly suggests the same potential ease of journey for the soul to heaven, in spite of imperfection, such as killing to eat, as the bird eats the angle worm.

See also

References

- Fr#359 in: Franklin, R. W., ed. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1999.

- Poem III.XXIII (pages 140-41) in: Higginson, T. W. & Todd, Mabel Loomis, ed. Poems by Emily Dickinson: Second Series. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1891.

- Helen Vendler. Dickinson: selected poems and commentaries. Harvard University Press. pp. 157ff.

- Harold Bloom. Emily Dickinson. Infobase Publishing. pp. 34ff.