1st Cavalry Division (Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

The 1st Cavalry Division was a horsed cavalry formation of the Royal Yugoslav Army that formed part of the Yugoslav 1st Army Group during the German-led Axis invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941. It was established in 1921, soon after the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (which became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). In peacetime, the division consisted of two cavalry brigade headquarters commanding a total of four regiments, but its wartime organisation specified one cavalry brigade headquarters commanding two or three regiments, as well as divisional-level combat and support units.

| 1st Cavalry Division | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1921–1941 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Royal Yugoslav Army |

| Type | Cavalry |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | 1st Army Group |

| Engagements | Invasion of Yugoslavia (1941) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Dragoslav Stefanović |

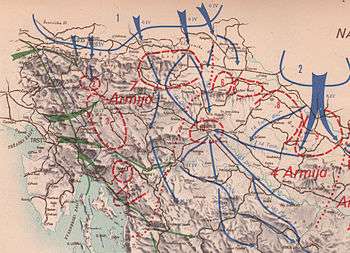

Along with the rest of the Yugoslav Army, the 1st Cavalry Division began mobilising on 3 April 1941 following a coup d'état, and was still engaged in that process three days later when the Germans began an air campaign and a series of preliminary operations against the Yugoslav frontiers. By the end of the following day, the division's cavalry brigade headquarters and all of the division's cavalry regiments had been detached for duty with other formations of the 1st Army Group. The divisional headquarters and divisional-level units remained in the vicinity of Zagreb until 10 April, when they were given orders to establish a defensive line southeast of Zagreb along the Sava River, with infantry and artillery support. The division had only begun to deploy for this task when the German 14th Panzer Division captured Zagreb. The divisional headquarters and all attached units were then captured by armed Croat fifth column groups, or surrendered to German troops.

- 1st Cavalry Division marked with a red 10 around Zagreb

- German attacks in blue

Background

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created with the merger of Serbia, Montenegro and the South Slav-inhabited areas of Austria-Hungary on 1 December 1918, in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The Army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was established to defend the new state. It was formed around the nucleus of the victorious Royal Serbian Army, as well as armed formations raised in regions formerly controlled by Austria-Hungary. Many former Austro-Hungarian officers and soldiers became members of the new army.[1] From the beginning, much like other aspects of public life in the new kingdom, the army was dominated by ethnic Serbs, who saw it as a means by which to secure political hegemony for the large Serb minority.[2]

The army's development was hampered by the kingdom's poor economy, and this continued during the 1920s. In 1929, King Alexander changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, at which time the army was renamed the Royal Yugoslav Army (Serbo-Croatian Latin: Vojska Kraljevine Jugoslavije, VKJ). The army budget remained tight, and as tensions rose across Europe during the 1930s, it became difficult to secure weapons and munitions from other countries.[3] Consequently, at the time World War II broke out in September 1939, the VKJ had several serious weaknesses, which included reliance on draught animals for transport, and the large size of its formations.[4] These characteristics resulted in slow, unwieldy formations, and the inadequate supply of arms and munitions meant that even the very large Yugoslav formations had low firepower.[5] Generals better suited to the trench warfare of World War I were combined with an army that was neither equipped nor trained to resist the fast-moving combined arms approach used by the Germans in their invasions of Poland and France.[6][7]

The weaknesses of the VKJ in strategy, structure, equipment, mobility and supply were exacerbated by serious ethnic disunity within Yugoslavia, resulting from two decades of Serb hegemony and the attendant lack of political legitimacy achieved by the central government.[8][9] Attempts to address the disunity came too late to ensure that the VKJ was a cohesive force. Fifth column activity was also a serious concern, not only from the Croatian nationalist Ustaše but also from the country's Slovene and ethnic German minorities.[8]

Formation and composition

Peacetime organisation

The 1st Cavalry Division was established soon after the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and was part of the army order of battle formalised in 1921, at which time it consisted of four regiments.[10] According to regulations issued by the VKJ in 1935,[11] the 1st Cavalry Division was headquartered in Zagreb during peacetime, and was under the control of Cavalry Command in Belgrade, as was the 2nd Cavalry Division, which was located in southeastern Yugoslavia at Niš. The division's units were manned by a mixture of full-time and part-time personnel. In peacetime, the 1st Cavalry Division comprised:[12][13]

- Headquarters 1st Cavalry Brigade in Čakovec near Zagreb

- Headquarters 2nd Cavalry Brigade in Subotica in the Banat north of Belgrade

- 2nd Cavalry Regiment, based in Virovitica on the Drava River in Slavonia

- 3rd Cavalry Regiment, based in Subotica

- 6th Cavalry Regiment, based in Zagreb

- 8th Cavalry Regiment, based in Čakovec

Wartime organisation

The wartime organisation of the Royal Yugoslav Army was laid down by regulations issued in 1936–1937, which introduced a requirement to raise a third cavalry division for war service.[14] The strength of a cavalry division was 6,000–7,000 men.[4] The theoretical war establishment of a fully mobilised Yugoslav cavalry division was:[13][15]

- headquarters and headquarters company

- a cavalry brigade consisting of 2 or 3 cavalry regiments

- an artillery battalion of four batteries, one of which was motorised and equipped with 47-millimetre (1.9 in) anti-tank guns

- a bicycle-mounted infantry battalion with three rifle companies and one machine gun company

- a signals squadron

- a bridging squadron equipped with pontoons

- a chemical defence platoon

- a divisional cavalry battalion consisting of two cavalry squadrons, a machine gun squadron, an engineer squadron and a bicycle company

- logistics units, including a transport battalion

Each cavalry regiment was to consist of four cavalry squadrons, a machine gun squadron, and an engineer squadron. Shortly before the war, an abortive attempt was made to motorise the 1st Cavalry Division, but this was stymied by a lack of motor transport and the division largely remained a horsed formation throughout its existence.[15] The 1st Cavalry Division was also never equipped with the planned motorised anti-tank battery,[16] and the divisional artillery battalion was largely equipped with World War I-vintage pieces.[17] Two peacetime components of the division, the Headquarters of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade and the 3rd Cavalry Regiment, were earmarked to join other formations when they were mobilised,[15] so the primary fighting formation of the 1st Cavalry Division was the 1st Cavalry Brigade, commanding the 2nd, 6th and 8th Cavalry Regiments.[13]

Deployment plan

In case of war, Yugoslav planners saw the 1st Cavalry Division as forming the reserve for the 1st Army Group.[18] The 1st Army Group was responsible for the defence of northwestern Yugoslavia, the 4th Army for defending the eastern sector along the Hungarian border, and the 7th Army for the German and Italian borders. The 1st Cavalry Division was to be deployed around Zagreb. On the left of the 4th Army, the boundary with the 7th Army ran from Gornja Radgona on the Mura through Krapina and Karlovac to Otočac. On the right of the 4th Army was the 2nd Army of the 2nd Army Group, the boundary running from just east of Slatina through Požega towards Banja Luka. The Yugoslav defence plan saw the 1st Army Group deployed in a cordon, the 4th Army behind the Drava River between Varaždin and Slatina,[19] and the 7th Army along the border region from the Adriatic in the west to Gornja Radgona in the east.[20] The planners estimated that cavalry formations would take four to seven days to mobilise.[21]

Mobilisation

After unrelenting pressure from Adolf Hitler to join the Axis powers, Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941. Two days later, a military coup d'état overthrew the government that had signed the pact, and a new government was formed under the Royal Yugoslav Army Air Force commander, Armijski đeneral[lower-alpha 1] Dušan Simović.[23] A general mobilisation was not called by the new government until 3 April 1941, out of fear of offending Hitler and thus precipitating war.[24] The same day as the coup, Hitler had issued Führer Directive 25, which called for Yugoslavia to be treated as a hostile state; on 3 April, Führer Directive 26 was issued, detailing the plan of attack and the command structure for the invasion, which was to commence on 6 April.[25]

According to the Yugoslav historian Velimir Terzić, on 6 April the mobilisation of the division was proceeding slowly due to the low number of conscripts that reported for duty, and the poor provision of animals and vehicles. A large portion of the strength of the division had been earmarked to be detached to one of the formations of the 4th Army, Detachment Ormozki.[26]

The commander of the 1st Cavalry Division was Divizijski đeneral[lower-alpha 2] Dragoslav Stefanović.[13] While the divisional headquarters and other divisional-level units were mobilising in Sesvete near Zagreb, the headquarters of the 1st Cavalry Brigade had been designated to command Detachment Ormozki, and the 6th and 8th Cavalry Regiments and the divisional artillery battalion had also been allocated to that formation. This reduced the main fighting elements of the division to a single cavalry regiment (the 2nd), which was mobilising in Virovitica.[26] The rest of the 1st Army Group reserve comprised an independent artillery battalion mobilising in Zagreb, and the 110th Infantry Regiment which was moving to Zagreb from Celje, a distance of 114 km (71 mi) to the northwest. By early morning of 6 April 1941 when the invasion commenced, the 110th Regiment had reached Zidani Most, still some 90 km (56 mi) from Zagreb.[26]

Operations

Stripped of most of its subordinate units, the 1st Cavalry Division remained in reserve near Zagreb during the first few days of fighting. On 10 April, due to the critical situation on the front of the 4th Army, the division was directed to take under its command the 110th Infantry Regiment and the independent artillery battalion, and defend against crossings of the 110-kilometre (68 mi) stretch of the River Sava between Jasenovac and Zagreb, while collecting stragglers and organising resistance. These orders were quickly overtaken by the rapid advance of the 14th Panzer Division to Zagreb when it broke out of its bridgehead across the Drava River at Zákány on the Hungarian border.[27] By 19:30 on 10 April, lead elements of the 14th Panzer Division had reached the outskirts of Zagreb, having covered nearly 160 km (99 mi) in a single day.[28] Armed fifth column Ustase groups and German troops disarmed the division and its attached units before they could establish any coherent defence along the Sava.[27]

On 15 April, orders were received that a ceasefire had been agreed, and that all VKJ troops were to remain in place and not fire on German personnel.[29] After a delay in locating appropriate signatories for the surrender document, the Yugoslav Supreme Command unconditionally surrendered in Belgrade effective at 12:00 on 18 April.[30] Yugoslavia was then occupied and dismembered by the Axis; Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and Albania all annexed parts of its territory.[31] Almost all of the Croat members of the division taken as prisoners of war were soon released by the Germans; 90 per cent of those held for the duration of the war were Serbs.[32]

Notes

- Equivalent to a U.S. Army lieutenant general.[22]

- Equivalent to a U.S. Army major general.[22]

Footnotes

- Figa 2004, p. 235.

- Hoptner 1963, pp. 160–161.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 60.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 58.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 58–59.

- Hoptner 1963, p. 161.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 57.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 63.

- Ramet 2006, p. 111.

- Jarman 1997, p. 527.

- Terzić 1982, p. 99.

- Terzić 1982, pp. 99–102.

- Niehorster 2015c.

- Terzić 1982, p. 104.

- Terzić 1982, p. 107.

- Terzić 1982, p. 204.

- Terzić 1982, p. 119.

- Niehorster 2015a.

- U.S. Army 1986, p. 37.

- Geografski institut JNA 1952, p. 1.

- Terzić 1982, p. 195.

- Niehorster 2015b.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 34–43.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 64.

- Trevor-Roper 1964, pp. 108–109.

- Terzić 1982, p. 260.

- Terzić 1982, p. 373.

- U.S. Army 1986, p. 58.

- Terzić 1982, pp. 444–445.

- U.S. Army 1986, pp. 63–64.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 89–95.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 73–74.

References

Books

- Figa, Jozef (2004). "Framing the Conflict: Slovenia in Search of Her Army". Civil-Military Relations, Nation Building, and National Identity: Comparative Perspectives. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-04645-2.

- Geografski institut JNA (1952). "Napad na Jugoslaviju 6 Aprila 1941 godine" [The Attack on Yugoslavia of 6 April 1941]. Istorijski atlas oslobodilačkog rata naroda Jugoslavije [Historical Atlas of the Yugoslav Peoples Liberation War]. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Vojnoistorijskog instituta JNA [Military History Institute of the JNA]. OCLC 504206827.

- Hoptner, J. B. (1963). Yugoslavia in Crisis, 1934–1941. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 404664 – via Questia.

- Jarman, Robert L., ed. (1997). Yugoslavia Political Diaries 1918–1965. 1. Slough, Berkshire: Archives Edition. ISBN 978-1-85207-950-5.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Terzić, Velimir (1982). Slom Kraljevine Jugoslavije 1941 : uzroci i posledice poraza [The Collapse of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1941: Causes and Consequences of Defeat] (in Serbo-Croatian). II. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Narodna knjiga. OCLC 10276738.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1964). Hitler's War Directives: 1939–1945. London, UK: Sidgwick and Jackson. OCLC 852024357.

- U.S. Army (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 16940402. CMH Pub 104-4.

Websites

- Niehorster, Leo (2015a). "Balkan Operations Order of Battle Royal Yugoslavian Army 6th April 1941". Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Niehorster, Leo (2015b). "Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces Ranks". Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Niehorster, Leo (2015c). "Royal Yugoslavian Army Cavalry Division 6th April 1941". Leo Niehorster. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

_location_map.svg.png)