1993 Cambodian general election

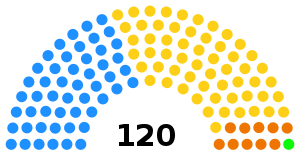

General elections were held in Cambodia between 23 and 28 May 1993. The result was a hung parliament with the FUNCINPEC Party being the largest party with 58 seats. Voter turnout was 89.56%.[1] The elections were conducted by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), which also maintained peacekeeping troops in Cambodia throughout the election and the period after it.[2]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 120 seats in the Constituent Assembly 61 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 4,764,618 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 4,267,192 (89.6%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Cambodia |

|

|

|

Monarchy

|

|

Government

|

|

|

|

They remain the last elections won by a party other than the Cambodian People's Party, which began to dominate Cambodian politics from 1998.

Background

The State of Cambodia (SOC) and three warring factions of the Cambodian resistance consisting of FUNCINPEC, Khmer Rouge and Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) signed the Paris Peace Accords in October 1991. The accords provides for the establishment of the UNTAC, a United Nations-led interim administration that would supervise the demobilization of troops from the SOC and the three warring factions, and also conduct democratic elections in 1993.[3] The UNTAC was formed at the end of February 1992, and Yasushi Akashi was appointed as head of the UNTAC.[4]

In August 1992, the UNTAC administration promulgated the election law,[5] and conducted the provisional registration of political parties. Political parties that were registered were allowed to open party offices the following month.[6] The following year in January 1993, registration of electorate was carried out, and UNTAC identity cards were issued.[7] The UNTAC conducted a civic education campaign in February 1993,[8] and two months later the UNTAC allowed political parties to hold public meetings and rallies to campaign for votes.[9]

Pre-election challenges

Demobilisation

When UN peacekeepers were sent in to commence on demobilisation in June 1992, the Khmer Rouge set up road blocks in territories under their control to prevent peacekeepers from entering.[10] When the incidents were reported to the then-UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali, he sent a personal appeal to Khieu Samphan to let peacekeepers conduct demobilisation. The Khmer Rouge leadership responded by demanding that day-to-day administration should be handed over an administrative body headed by Norodom Sihanouk, and also alleged that continued presence of Vietnamese troops in Cambodia did not warrant demobilisation. As the Khmer Rouge insisted on not participating in demobilisation, Sihanouk called on the UNTAC to isolate the Khmer Rouge from participating in any future peace-making initiatives.[11]

The Cambodian People's Armed Forces (CPAF), Armee Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS, also informally known as the FUNCINPEC army) and Khmer People's National Liberation Front participated in the mobilisation exercises, although young and untrained recruits were sent to participate while non-servicing weapons were presented to the peacekeeping troops.[12] When the Khmer Rouge continued to resist demobilisation efforts, UNTAC decided to suspend the entire mobilisation exercise in September 1992, during which about 50,000 soldiers from the CPAF, ANS and KPNLF have disarmed.[13]

Violent attacks

The Khmer Rouge started to carry out a series of attacks on Vietnamese civilians from April 1992,[14] which they justified by claiming that there were Vietnamese soldiers disguised as civilians.[15] In March 1993, the Khmer Rouge carried out the largest attack on Vietnamese civilians in the floating village of Chong Kneas in Siem Reap Province which claimed the lives of 124 Vietnamese civilians. The Khmer Rouge had provided tacit forewarning prior to the attack,[16] but neither SOC troops not UNTAC peacekeepers were deployed. When the attack was published in the press, it triggered about 20,000 Vietnamese to flee to Vietnam the following month in April 1993.[17]

The CPAF also carried out clandestine attacks on the party offices belonging to FUNCINPEC and BLDP starting in November 1992. The attacks were carried out at night, and soldiers would fire grenades or rockets. The number of incidents were reduced in January 1993, but picked up again in March 1993 until the eve of elections in May 1993.[18] The attacks left about 200 political workers killed or injured by May 1993.[19]

Results

The voting process was carried out between 23 and 28 May 1993.[20] Most of the voting stations were based in school buildings and Buddhist pagodas to reduce costs. The election was staffed by some 50,000 Cambodians and 900 international volunteers as well as an additional 1,400 United Nation officers which served as polling station observers.[21] The counting of votes started on 29 May and lasted until 10 June. The results were declared by Akashi, and five days later the UN security council endorsed the election results with Security Council Resolution 840.[22]

| ||||||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUNCINPEC | 1,824,188 | 45.5 | 58 | |||||

| Cambodian People's Party | 1,533,471 | 38.2 | 51 | |||||

| Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party | 152,764 | 3.8 | 10 | |||||

| Liberal Democratic Party | 62,698 | 1.6 | 0 | |||||

| MOULINAKA | 55,107 | 1.4 | 1 | |||||

| Khmer Neutral Party | 48,113 | 1.2 | 0 | |||||

| PD | 41,799 | 1.0 | 0 | |||||

| Free Independent Democracy Party | 37,474 | 0.9 | 0 | |||||

| Free Republican Party | 31,348 | 0.8 | 0 | |||||

| Liberal Reconciliation Party | 29,738 | 0.7 | 0 | |||||

| Cambodge Renaissance Party | 28,071 | 0.7 | 0 | |||||

| Republican Coalition Party | 27,680 | 0.7 | 0 | |||||

| Khmer National Congress Party | 25,751 | 0.6 | 0 | |||||

| Neutral Democratic Party of Cambodia | 24,394 | 0.6 | 0 | |||||

| Khmer Farmer Liberal Democracy | 20,776 | 0.5 | 0 | |||||

| Free Development Republican Party | 20,425 | 0.5 | 0 | |||||

| Rally for National Solidarity | 14,569 | 0.4 | 0 | |||||

| Action for Democracy and Development | 13,914 | 0.4 | 0 | |||||

| Republican Democracy Khmer Party | 11,524 | 0.3 | 0 | |||||

| Nationalist Khmer Party | 7,827 | 0.2 | 0 | |||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 255,561 | – | – | |||||

| Total | 4,267,192 | 100 | 120 | |||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 4,764,618 | 89.56 | – | |||||

| Source: Nohlen et al.[23] | ||||||||

Aftermath

On 31 May 1993, the CPP to file a complaint with Akashi over claims of irregularities in the elections. When Akashi dismissed CPP's complaints, Hun Sen and Chea Sim suggested to Sihanouk to assume full executive powers as the Head of State of the country.[1] Sihanouk accepted the initiative, and issued a declaration on 3 June that he would assume the position as the Head of State of Cambodia. The ministries would be divided between FUNCINPEC and CPP on a fifty-fifty basis. FUNCINPEC president Ranariddh, as well as several countries including the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and China opposed the initiative. The US charged that Sihanouk's initiative would violate the spirit of the election as well as the terms set in the Paris Peace Accords. The following day, Sihanouk abandoned the initiative to assume full executive powers.[24]

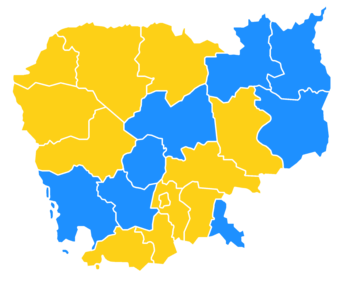

One week later on 10 June, Hun Sen announced that seven eastern provinces, all bordering Vietnam had seceded from Cambodia under the leadership of then-Deputy Prime Minister Norodom Chakrapong and then-Interior Minister Sin Song. Hun Sen avoided supporting the secession attempt publicly, but accused the United Nations of creating electoral fraud to precipitate CPP's defeat in the election. Chakrapong and Sin Song attacked political offices belonging to FUNCINPEC and BLDP in the provinces, and also issued orders for UNTAC officials to leave the provinces under their control. An emergency National Assembly meeting was initiated on 14 June where Sihanouk was re-instated as the Head of State, with Ranariddh and Hun Sen appointed as co-prime ministers with equal levels of executive powers.[25] When Hun Sen issued a letter to Akashi to declare his support for continued UNTAC's interim administration, Chakrapong and Sin Song dropped the secessionist threats.[26] For the next three months, Sihanouk presided over an interim administration his resignation on 21 September, and he re-assumed the office of the King of Cambodia two days later on 23 September 1993.[27]

References

- Widyono (2008), p. 124

- UN Security Council Practices and Charter Research Branch (1995), p. 598

- Widyono (2008), p. 35

- Widyono (2008), p. 5

- Widyono (2008), p. 95

- Widyono (2008), p. 116

- Widyono (2008), p. 115

- Widyono (2008), p. 117

- Widyono (2008), p. 118

- Widyono (2008), p. 77

- Widyono (2008), pp. 84–5

- Widyono (2008), p. 76

- Widyono (2008), p. 78

- Ben Kiernan (20 November 1992). "COMMENT: U.N.'s Appeasement Policy Falls into Hands of Khmer Rouge Strategists". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Heder et al. (1995), p. 98

- Widyono (2008), p. 96

- Widyono (2008), pp. 97–8

- Heder et al. (1995), p. 170

- Heder et al. (1995), p. 196

- Widyono (2008), p. 119

- Widyono (2008), p. 120

- Widyono (2008), p. 127

- Nohlen et al. (2001), p. 70

- Widyono (2008), p. 126

- Widyono (2008), pp. 128–9

- Ker Munthit (18 June 1993). "Chakrapong-led Secession Collapses". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Widyono (2008), p. 130

Bibliography

Books

- Heder, Stepher R.; Ledgerwood, Julie (1995). Propaganda, Politics and Violence in Cambodia: Democratic Transition Under United Nations Peace-Keeping. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765631741.

- Nohlen, D.; Grotz, F.; Hartmann, C. (2001). Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume II. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924959-8.

- Widyono, Benny (2008). Dancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and the United Nations in Cambodia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0742555534.

Reports

- UN Security Council Practices; Charter Research Branch (1995). "Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council–Asia–14. The situation in Cambodia" (PDF). Modern Asian Studies. United Nations Security Council: 596–612. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

.jpg)