1964 Pacific hurricane season

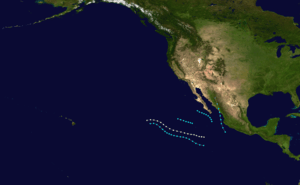

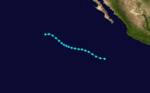

The 1964 Pacific hurricane season was the least active Pacific hurricane season on record since 1953. The season officially started on May 15 in the eastern Pacific and June 1 in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility and lasted until November 30 in both regions. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean.[1]

| 1964 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 6, 1964 |

| Last system dissipated | September 9, 1964 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Odessa |

| • Maximum winds | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 986 mbar (hPa; 29.12 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 6 |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 1 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | Unknown |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

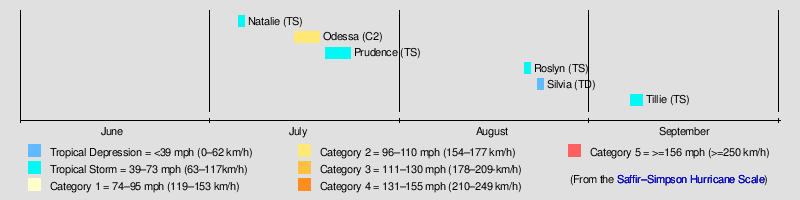

During this season only six tropical storms developed, of which two intensified into hurricanes. Of the two hurricanes, one reached Category 2 intensity of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. No storms reached major hurricane status (Category 3 or higher on the hurricane scale), an unusual occurrence. The first tropical cyclone of the season, Tropical Storm Natalie made landfall in Mexico in early to mid-July. About a week later, Hurricane Odessa became the strongest storm of the season in terms of wind speed. Tropical Storm Prudence brought high waves to Southern California, while becoming the strongest storm of the year in terms of barometric pressure. In addition, Tropical Storm Tillie produced severe flooding to much of the Southwestern United States, in particular in Arizona in early to mid-September.

Seasonal summary

With only six named storms, the season was well below the 1949–2006 average of 13 named storms and is the second fewest storms in the hurricane database, only behind the 1953 Pacific hurricane season, in which just 5 storms were observed.[2] Moreover, 1964 is the least active season since the satellite era began in the basin in 1961.[3][4] Of the six storms that formed, three formed in July, two developed in August, and the final storm of the year existed in early to mid-September.[3] Only two tropical cyclones reached hurricane status,[5] compared to the modern-day average of seven. Furthermore, 1964 is also one of the few seasons without a major hurricane. This season was part of a decade-long absence of major hurricanes; during the 1960s, only one major hurricane was observed and none were noted from 1960–1966. However, it is possible that some storms were missed due to the lack of satellite coverage in the region; at that time, satellite data was still scarce, and 1964 is still two years shy of the start of the geostationary satellite era, which began in 1966.[2] Some efforts are underway to improve the records for this time period; however, this process will likely take years to complete.[4] Also, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) was in the midst of a cold phase during this time period, which tends to suppress Pacific hurricane activity.[3][6][7] During the season, tropical cyclone advisories were issued by the Naval Fleet Warning Central (NFWC) in Alameda, which held responsibility for the basin until 1970.[2]

Systems

Tropical Storm Natalie

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 6 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

On July 5, the ship California Star recorded winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1,005.8 mb (30 inHg);[5] consequently, the storm was upgraded into Tropical Storm Natalie.[3] After passing through the Tres Marinas Islands just offshore, Natalie attained its peak intensity of 80 mph (130 km/h) (making Natalie a Category 1 hurricane on the present-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) and a peak pressure of 1,001 mb (29.6 inHg), though the Pacific hurricane database does not show the storm getting any stronger than 50 mph (80 km/h).[5] The next day, July 7, the NFWC reported that Natalie made landfall near Mazatlan with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) just before dissipating.[3] No known impact was recorded.[5]

Hurricane Odessa

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 15 – July 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane Odessa formed on July 15.[3] The storm quickly intensified and was believed to have attained peak intensity of 100 mph (160 km/h), making Odessa a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. After moving west, Odessa steadily weakened, and by July 18, the winds had decreased to 40 mph (65 km/h).[5] Later on July 18, it turned towards the northwest, and shortly thereafter, the hurricane turned towards the west-southwest.[3] Odessa quickly re-intensified, and according to ship reports, the storm attained winds of 70 mph (115 km/h).[5] Odessa dissipated at 1800 UTC on July 19.[3] Even though the storm was about 250 mi (400 km) south of Socorro Island at the time of its formation, tropical cyclone warnings and watches were posted for the island.[5]

Tropical Storm Prudence

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 20 – July 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

Near the area where Odessa developed,[5] a mid-level tropical storm formed early on July 20[3] and it was named Prudence, despite ships in the vicinity of the storm reporting winds of 35 mph (55 km/h).[5] Moving generally west-northwest, Prudence initially failed to intensify, and maintained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) for a few days. After briefly turning west on July 22, Prudence resumed a west-northwest course[3] while attaining its peak wind speed of 70 mph (115 km/h). Prudence held on to this intensity until July 23, when it encountered cooler sea surface temperatures.[5] Shortly before dissipating, the system turned back towards the west. Tropical Storm Prudence dissipated on July 24.[3] Even though Prudence never made landfall, the cyclone produced high waves along the California coast, especially along Newport Beach.[8]

Tropical Storm Roslyn

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed on August 21.[5] Later that day, the NFWC upgraded the depression into a tropical storm, and was named Roslyn, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). At the time of the upgrade, Tropical Storm Roslyn was located roughly 500 mi (805 km) south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas.[3] After passing east of Clarion Island during the evening hours of September 20, Roslyn attained its peak strength of 65 mph (105 km/h), making Roslyn a strong tropical storm.[5] While maintaining its intensity, Roslyn drifted west-northwest. The storm dissipated at 1800 UTC on August 22.[3]

Tropical Depression Silvia

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 23 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Silvia was first noted by the NFWC on August 23 about 60 mi (95 km) south of Mazatlan, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). After tropical cyclogenesis, the storm quickly weakened. Simultaneously, Silvia moved westward, passing about 60 mi (95 km) south of Cabo San Lucas. By August 24, the NFWC had stopped monitoring the system. The depression was named by the NFWC as it resembled to be a tropical storm. However, post-storm analysis show that Silvia never attained tropical storm status.[5]

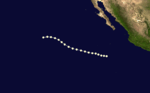

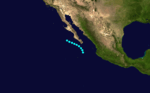

Tropical Storm Tillie

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

The last tropical cyclone of the season, Tropical Storm Tillie, developed on September 7. At first, the cyclone moved north-northwest;[3] Tillie reached its peak intensity of 60 mph (95 km/h) at that time of its formation approximately 150 mi (240 km) west of Mazatlan.[5] Early on September 8, while located about 100 mi (160 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Tillie began a gradual turn towards the west-northwest. Tropical Storm Tillie dissipated at 0600 UTC on September 9[3] off the coast of California,[9] having only been a tropical cyclone for just over two days.[3]

When Tillie posed a threat to Baja California, winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) were forecast to occur.[10] The storm's residual moisture was adverted over southern Arizona, allowing a passing cold front to trigger widespread showers and thunderstorms on the evening of September 9.[11] The most significant rainfall was reported along southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico, and around El Paso.[12] Amado sustained 5.66 in (144 mm) in a 72‑hour time span. Furthermore, Tucson received 3.05 in (77 mm) of rainfall in a 24-hour period between September 9–10,[13] and two locations—one in the Catalina Mountain foothills and one near Sahuarita—recorded 6.75 in (171 mm) of precipitation. Coupled with rain during the previous week, the Santa Cruz River produced heavy runoff, with peak flows of 15,900 cu ft/s (450 m3/s) recorded near Cortaro.[11]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the eastern Pacific in 1964. No names were retired from this list. This is a part of list 2, which was used from 1960-1965.[14][15] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

|

See also

- Tropical cyclone

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- 1964 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1964 Pacific typhoon season

- 1964 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Pre-1980 Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone seasons

References

- Neal, Dorst. "When is hurricane season?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Todd Kimberlain; Department of Commerce; National Hurricane Center (April 16, 2012). Re-analysis of the Eastern North Pacific HURDAT. American Meteorological Society.

- McGurrin, Martin (1964). Rosendal, Hans E (ed.). Tropical Cyclones in the Eastern Pacific 1964 (Mariners Weather Log: Volume 9, Issue 2: March 1964). United States Weather Bureau. pp. 42–45.

- "Variability of rainfall from tropical cyclones in Northwestern Mexico" (PDF). Atmosfera. 2008. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Franco Biondi; Alexander Gershunov; Daniel R. Cayan (2001). "North Pacific Decadal Climate Variability since 1661". Journal of Climate. 14 (1): 5–10. Bibcode:2001JCli...14....5B. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<0005:NPDCVS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- "Towering surf hits California". Tri-City Herald. July 21, 1964. p. 1A.

- "Tilie Is Weakening Off Of California". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. September 9, 1964. p. 6. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Tropical Storm Tillie Weakens". The Free Lance. September 9, 1962. p. 2. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. "Santa Cruz River, Paseo de las Iglesias (Pima County, Arizona) Final Feasibility Report and Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). USACE. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- "The Effects of Tropical Cyclones on the Southwestern United States" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memorandum. National Weather Service Western Region. August 1986. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- Green, Raymond, A. (December 1964). <0601:TWACOS>2.3.CO;2 "The Weather and Circulation of September 1964". Monthly Weather Review. 92 (12): 601–606. Bibcode:1964MWRv...92..601G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1964)092<0601:TWACOS>2.3.CO;2.

- Unattributed (1970). "National Hurricane Operations Plan 1970 – Tropical Cyclone Names" (PDF). Environmental Science Services Administration, Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. US Department of Commerce. pp. 96–98. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- Padgett, Gary (July 11, 2008). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary: November 2007 First Installment". Australian Severe Weather. Retrieved February 10, 2010.