1947 Sydney hailstorm

The 1947 Sydney hailstorm was a natural disaster which struck Sydney, Australia, on 1 January 1947. The storm cell developed on the morning of New Year's Day, a public holiday in Australia, over the Blue Mountains, hitting the city and dissipating east of Bondi in the mid-afternoon. At the time, it was the most severe storm to strike the city since recorded observations began in 1792.[1][2]

A boat at Rose Bay in water which is being churned by the hailstones. | |

| Formed | 10:00 am, 1 January 1947 Over Blue Mountains |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | 3:30 pm, 1 January 1947 East of Bondi, offshore |

| Damage | GB£750,000 (est., 1947) A$45 million (est., 2007) |

| Areas affected | Sydney |

The high humidity, temperatures and weather patterns of Sydney increased the strength of the storm. The cost of damages from the storm were, at the time, approximately GB£750,000 (US$3 million); this is the equivalent of around A$45 million in modern figures.[3] The HP supercell dropped hailstones larger than 8 centimetres (3.1 in) in diameter,[4][5] with the most significant damage occurring in the central business district and eastern suburbs of Sydney.[6][7]

The event caused around 1000 injuries, with between 200 and 350 people requiring hospitalisation or other medical attention, predominantly caused by broken glass shards.[4][8] The majority of severe injuries reported were suffered by people on Sydney's beaches, where many were without shelter.[1] The size of the hailstones were the largest seen in Sydney for 52 years, until the 1999 Sydney hailstorm caused A$1.7 billion in insured damage in becoming the costliest natural disaster in Australian history.[5]

Conditions and climatology

During the spring and summer, conditions along the east coast of Australia are highly conducive for the formation of hailstorms. The variation of air temperature in the atmosphere; with warm and humid air close to the ground and colder air above it causes instability, and the cold upper atmosphere temperatures allow the precipitation to fall in solid form as hailstones.[9] Since records began in 1791, hailstorms in the month of January form approximately 13% of the total number of hailstorms in the Sydney metropolitan area, and over 15% of all events with 'large hail'.[10]

Hailstorms have a history of significant damage in Australia. Since records on insured losses began in 1967, four hailstorms—Sydney in 1986, 1990 and 1999, as well as Brisbane in 1985—have featured on the top ten list of most insured damages caused by a single Australian natural disaster. Hailstorms caused more than 30% of all insured damages inflicted as a result of natural disasters in Australia during this period, and around three quarters of all hailstorm damage has occurred in New South Wales.[11]

The conditions on New Year's Day, 1947 were meteorologically sound for the formation of a storm. The day was hot and humid, with the maximum temperature recorded during the day being 32.7 °C (90.9 °F) and humidity reaching 73%.[12] Many Sydneysiders travelled to the beaches along the coastline to benefit from the afternoon sea breeze. The general weather pattern for Sydney in summer is movement from the west to the east—from over the Blue Mountains to across the city and into the Tasman Sea.[1]

Progression of the storm

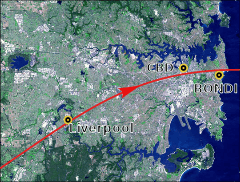

Developing from the Blue Mountains to the south-west of Sydney in the morning of 1 January 1947, the storm cell was first identified at 10:00 am by weather observers at Mascot.[7] The formation of storms in this region is not unusual, especially given the hot and humid conditions at ground level which causes atmospheric instability. However, the Bureau of Meteorology reported that the formation of the storm was different from most others, describing how "the underpart of the cloud was mottled and serrated or curtained, rather than mammilated, and looked angry black, while false cirrus tufts were discernible at the top".[1][2]

The storm cell dropped hailstones the size of billiard balls across the south-western suburbs of Sydney. It moved directly over Liverpool at 2:25 pm, heading in a north-east direction before slowly bending its path and travelling almost due east as it passed over the southern part of the central business district.[7] "Large explosion-like sounds", presumed to be thunder by the Bureau, were heard around the Sydney Harbour Bridge.[13] The sounds were described by the Bureau—who were based at Observatory Hill, next to the southwest pylon of the Bridge, in 1947—as a "terrific noise" akin to "several trains ... passing over [the Bridge]".[2]

The storm unusually intensified as it cut through the suburbs, and eventually unleashed its full power across the eastern suburbs of Sydney. The suburbs most seriously affected were Surry Hills, south of the central district, as well as Bondi and Rose Bay in the Waverley region which were struck at around 2:40 pm.[6][8] The hailstorm pelted beach-goers, particularly at Bondi Beach, and the situation was described by a Second World War veteran as "though [he] was back in the firing line overseas".[13] The hail in the coastal regions was described as being of similar size to a cricket ball.[7]

Aftermath

The most damage was caused when the storm was its most intense, over the eastern suburbs of the city. According to the Bureau of Meteorology, over 5000 roofs were damaged in Waverley by the lumps of hail which weighed up to 1.8 kg (4.0 lb).[5][8] No official cost total exists for the amount of damage caused by the 1947 hailstorm, however a Reuters article published in The New York Times on 2 January estimated preliminary damage to be worth around US$3 million, equivalent to GB£750,000.[3] This is approximately equal to A$45 million in modern figures, placing it well below the costliest natural disasters in Australian history; this, given the severity of the storm cell, is attributable mainly to the relative inexpensiveness of buildings and other items of the era.[13][14] More definite historical accounts exist for damage caused to certain buildings. The historic skylight which runs through the centre of the main Central railway station building was smashed, and the shards reportedly fell in sizes up to 26 cm2 (4 sq in) on around 100 waiting passengers.[13][15]

Convertible cars, in fashion at the time of the storm, also sustained severe damage, mainly punctures to the soft-top roofs, and trams that ran through the eastern suburbs at the time also suffered damage.[7][13] According to veteran meteorologist Richard Whitaker, "Sydney was staggered by the enormity of the incident, as there had not been even a remotely similar storm in living memory".[4] The problems were exacerbated due to a lack of building materials available for use in repair work, a result of the Second World War which had concluded only 18 months prior. This contributed to the delays which resulted in houses still covered with only temporary tarpaulins several years later.[4]

Most of the approximately 1000 injuries were caused by the hailstones directly striking people or from flying debris, with the latter mainly from shattered windows.[4][16] Of these, between 200 and 350 people required hospitalisation or other medical attention, however figures vary between different sources.[4][8] The storm struck during the afternoon of a public holiday—New Year's Day—which produced hot and humid conditions, and the beaches in the eastern suburbs were significantly populated.[1] The beach-goers were exposed to the large hail when the storm cell reached the coastline, and according to the front page report in The Sydney Morning Herald the following day, "[f]or nearly three hours, ambulance wagons travelled from the eastern suburbs beaches with the injured".[15] The 8 cm (3.1 in) hailstones which fell during the 1947 event were not matched in Sydney for 52 years, until the 1999 hailstorm, which caused A$1.7 billion in insured damage—the costliest natural disaster in Australian history.[5]

Notes

- Whitaker (2005), p. 94.

- Newman (1947), p. 23.

- Reuters (1947), p. 4.

- Whitaker (2005), p. 98.

- Lee, et al. (2000), p. 579.

- Whitaker (2005), p. 95.

- Newman (1947), p. 26.

- Emergency Management Australia (2007).

- Whitaker (2005), p. 93.

- Schuster, et al. (2005a), pp. 1641–1643.

- Schuster, et al. (2005b), p. 1.

- Newman (1947), p. 27.

- Whitaker (2005), 96.

- Hunter (1998).

- "ICE STORM LASHES CITY AND SUBURBS". The Sydney Morning Herald (34, 018). New South Wales, Australia. 2 January 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 11 September 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

"SCENES OF DEVASTATION AFTER FREAK HAIL HIT CITY". The Sydney Morning Herald (34, 018). New South Wales, Australia. 2 January 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 11 September 2016 – via National Library of Australia. - Newman (1947), p. 24.

References

- Emergency Management Australia (7 August 2007). "Sydney, NSW: Severe Hailstorm - 1 January 1947". Australian Government - Attorney-General's Department. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- Hunter, Laraine (March 1998). "Perils, Postcodes & Risk Accumulation Zones". Natural Hazards Quarterly. 4 (1): 1–3.

- Lee, Lynette; Collings, Anne (2000). "Sydney hailstorms: the health role in the recovery process". Medical Journal of Australia. 173 (11–12): 579–582. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb139348.x. PMID 11379494.

- Newman, Barney (1947). Phenomenal Hailstorm with Thunderstorm, Sydney 1 January 1947. Sydney, Australia: Bureau of Meteorology.

- "Hailstones Pelt Sydney; Damage and Injuries High". The New York Times. Reuters. 2 January 1947. p. 4.

- Schuster, Sandra; Blong, Russell; Speer, Milton (2005a). "A hail climatology of the greater Sydney area and New South Wales, Australia". International Journal of Climatology. New York City, United States: Wiley. 25 (12): 1633–1650. Bibcode:2005IJCli..25.1633S. doi:10.1002/joc.1199.

- Schuster, Sandra; Blong, Russell; Leigh, Roy; McAneney, John (2005b). "Characteristics of the 14 April 1999 Sydney hailstorm based on ground observations, weather radar, insurance data and emergency calls" (PDF). Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (2 January 1947). "Ice Storm Lashes City and Suburbs". pp. 1, 4–5.

- Whitaker, Richard (2005). Australia's Natural Disasters. Sydney, Australia: Reed New Holland. pp. 93–98. ISBN 1-877069-04-3.

Further reading

- Batt, K.; Casinader, T.; Colquhoun, J.; Griffiths, D. (December 1993). "Severe Thunderstorms in New South Wales: Climatology and Means of Assessing the Impact of Climate Change". Climatic Change. The Netherlands: Springer. 25 (3–4): 369–388. Bibcode:1993ClCh...25..369G. doi:10.1007/bf01098382. ISSN 1573-1480.

- Keenan, T.; May, P.; Potts, R. (September 2000). <3308:rcosit>2.0.co;2 "Radar Characteristics of Storms in the Sydney Area". Monthly Weather Review. Melbourne: Bureau of Meteorology Research Centre. 128 (9): 3308–3319. Bibcode:2000MWRv..128.3308P. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2000)128<3308:rcosit>2.0.co;2. ISSN 1520-0493.