14-3-3 protein

14-3-3 proteins are a family of conserved regulatory molecules that are expressed in all eukaryotic cells. 14-3-3 proteins have the ability to bind a multitude of functionally diverse signaling proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, and transmembrane receptors. More than 200 signaling proteins have been reported as 14-3-3 ligands.

| 14-3-3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | 14-3-3 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00244 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000308 | ||||||||

| SMART | 14_3_3 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00633 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 1a4o / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Elevated amounts of 14-3-3 proteins are found in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[2]

Properties

There are seven genes that encode seven distinct 14-3-3 proteins in most mammals (See Human genes below) and 13-15 genes in many higher plants, though typically in fungi they are present only in pairs. Protists have at least one. Eukaryotes can tolerate the loss of a single 14-3-3 gene if multiple genes are expressed, however deletion of all 14-3-3s (as experimentally determined in yeast) results in death.

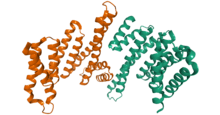

14-3-3 proteins are structurally similar to the Tetratrico Peptide Repeat (TPR) superfamily, which generally have 9 or 10 alpha helices, and usually form homo- and/or hetero-dimer interactions along their amino-termini helices. These proteins contain a number of known common modification domains, including regions for divalent cation interaction, phosphorylation & acetylation, and proteolytic cleavage, among others established and predicted.[3]

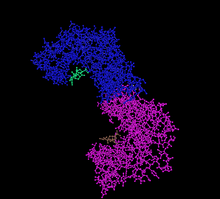

14-3-3 binds to peptides. There are common recognition motifs for 14-3-3 proteins that contain a phosphorylated serine or threonine residue, although binding to non-phosphorylated ligands has also been reported. This interaction occurs along a so-called binding groove or cleft that is amphipathic in nature. To date, the crystal structures of six classes of these proteins have been resolved and deposited in the public domain.

| Canonical |

R[^DE]{0,2}[^DEPG]([ST])(([FWYLMV].)

|([^PRIKGN]P)

|([^PRIKGN].{2,4}[VILMFWYP])) |

|---|---|

| C-terminal |

R[^DE]{0,2}[^DEPG]([ST])[^P]{0,1}$ |

| Non-phos (ATP) |

IR[^P][^P]N[^P][^P]WR[^P]W[YFH][ITML][^P]Y[IVL] |

| All entrys are in regular expression format. Newlines are added in "or" cases for readability. Phosphorylation sites are in bold.

The motif sites are way more diverse than the patterns here suggest. For an example with a modern recognizer using an artificial neural network, see the cited article.[5] | |

Discovery and naming

14-3-3 proteins were initially found in brain tissue in 1967 and purified using chromatography and gel electrophoresis. In bovine brain samples, 14-3-3 proteins were located in the 14th fraction eluting from a DEAE-cellulose column and in position 3.3 on a starch electrophoresis gel.[6]

Function

14-3-3 proteins play an isoform-specific role in class switch recombination. They are believed to interact with the protein Activation-Induced (Cytidine) Deaminase in mediating class switch recombination.

Phosphorylation of Cdc25C by CDS1 and CHEK1 creates a binding site for the 14-3-3 family of phosphoserine binding proteins. Binding of 14-3-3 has little effect on Cdc25C activity, and it is believed that 14-3-3 regulates Cdc25C by sequestering it to the cytoplasm, thereby preventing the interactions with CycB-Cdk1 that are localized to the nucleus at the G2/M transition.[7]

The eta isoform is reported to be a biomarker (in synovial fluid) for rheumatoid arthritis.[8]

Human genes

- YWHAB – "14-3-3 beta"

- YWHAE – "14-3-3 epsilon"

- YWHAG – "14-3-3 gamma"

- YWHAH – "14-3-3 eta"

- YWHAQ – "14-3-3 tau"

- YWHAZ – "14-3-3 zeta"

- SFN or YWHAS – "14-3-3 sigma" (Stratifin)

The 14-3-3 proteins alpha and delta (YWHAA and YWHAD) are phosphorylated forms of YWHAB and YWHAZ, respectively.

In plants

Presence of large gene families of 14-3-3 proteins in the Viridiplantae kingdom reflects their essential role in plant physiology. A phylogenetic analysis of 27 plant species clustered the 14-3-3 proteins into four groups.

14-3-3 proteins activate the auto-inhibited plasma membrane P-type H+ ATPases. They bind the ATPases' C-terminus at a conserved threonine.[10]

References

- Yang, X.; Lee, W. H.; Sobott, F.; Papagrigoriou, E.; Robinson, C. V.; Grossmann, J. G.; Sundstrom, M.; Doyle, D. A.; Elkins, J. M. (2006). "Structural basis for protein-protein interactions in the 14-3-3 protein family". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (46): 17237–17242. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317237Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605779103. PMC 1859916. PMID 17085597.

- Takahashi H, Iwata T, Kitagawa Y, Takahashi RH, Sato Y, Wakabayashi H, Takashima M, Kido H, Nagashima K, Kenney K, Gibbs CJ, Kurata T (November 1999). "Increased levels of epsilon and gamma isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 6 (6): 983–5. doi:10.1128/CDLI.6.6.983-985.1999. PMC 95810. PMID 10548598.

- Bridges D, Moorhead GB (August 2005). "14-3-3 proteins: a number of functions for a numbered protein". Science's STKE. 2005 (296): re10. doi:10.1126/stke.2962005re10. PMID 16091624.

- "ELM search: "14-3-3"". Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Madeira F, Tinti M, Murugesan G, Berrett E, Stafford M, Toth R, Cole C, MacKintosh C, Barton GJ (July 2015). "14-3-3-Pred: improved methods to predict 14-3-3-binding phosphopeptides". Bioinformatics. 31 (14): 2276–83. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv133. PMC 4495292. PMID 25735772.

- Aitken, A (2006). "14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview". Semin Cancer Biol. 50 (6): 993–1010. doi:10.1023/A:1021261931561. PMID 25735772.

- Cann KL, Hicks GG (December 2007). "Regulation of the cellular DNA double-strand break response". Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 85 (6): 663–74. doi:10.1139/O07-135. PMID 18059525.

- Detection of high levels of 2 specific isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins in synovial fluid from patients with joint inflammation.

- Saha M, Carriere A, Cheerathodi M, Zhang X, Lavoie G, Rush J, Roux PP, Ballif BA (October 2012). "RSK phosphorylates SOS1 creating 14-3-3-docking sites and negatively regulating MAPK activation". The Biochemical Journal. 447 (1): 159–66. doi:10.1042/BJ20120938. PMC 4198020. PMID 22827337.

- Jahn TP, Schulz A, Taipalensuu J, Palmgren MG (February 2002). "Post-translational modification of plant plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase as a requirement for functional complementation of a yeast transport mutant". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (8): 6353–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109637200. PMID 11744700.

Further reading

- Moore BW, Perez VJ (1967). FD Carlson (ed.). Physiological and Biochemical Aspects of Nervous Integration. Prentice-Hall, Inc., The Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA. pp. 343–359.

- Mhawech P (April 2005). "14-3-3 proteins--an update". Cell Research. 15 (4): 228–36. doi:10.1038/sj.cr.7290291. PMID 15857577.

- Steinacker P, Aitken A, Otto M (September 2011). "14-3-3 proteins in neurodegeneration". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 22 (7): 696–704. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.08.005. PMID 21920445.

External links

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_14-3-3_1

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_14-3-3_2

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_14-3-3_3

- 14-3-3+Protein at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Three-dimensional structure of 14-3-3 Protein Theta (Human) complexed with a peptide in the PDB.

- Drosophila 14-3-3epsilon - The Interactive Fly

- Drosophila 14-3-3zeta - The Interactive Fly