(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais

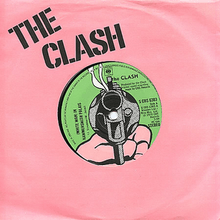

"(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" is a song by the English punk rock band the Clash. It was originally released as a 7-inch single, with the b-side "The Prisoner", on 16 June 1978 through CBS Records.

| "(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by The Clash | ||||

| from the album The Clash (US version) | ||||

| B-side | "The Prisoner" | |||

| Released | 16 June 1978 | |||

| Recorded | March–April 1978, Basing Street Studios, London | |||

| Genre | Punk rock, reggae rock | |||

| Length | 3:59 | |||

| Label | CBS S CBS 6383 | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Joe Strummer, Mick Jones | |||

| Producer(s) | Sandy Pearlman and The Clash | |||

| The Clash singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Produced by The Clash and engineered by Simon Humphries, the song was recorded for (but not included on) the group's second studio album Give 'Em Enough Rope; it was later featured on the American version of their debut studio album The Clash between the single version of "White Riot" and "London's Burning".

Inspiration and composition

The song showed considerable musical and lyrical maturity for the band at the time. Compared with their other early singles, it is stylistically more in line with their version of Junior Murvin's "Police and Thieves" as the powerful guitar intro of "(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" descends into a slower ska rhythm, and was disorienting to a lot of the fans who had grown used to their earlier work.[1] "We were a big fat riff group", Joe Strummer noted in the Clash's film Westway to the World. "We weren't supposed to do something like that."[2]

"(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" starts by recounting an all-night reggae "showcase" night at the Hammersmith Palais in Shepherd's Bush Road, London, that was attended by Joe Strummer, Don Letts and roadie Roadent, and was headlined by Dillinger, Leroy Smart and Delroy Wilson.[3] Strummer was disappointed and disillusioned that these performances had been more "pop" and "lightweight" similar to Ken Boothe's brand of reggae, using Four Tops-like dance routines,[1] and that the acts had been "performances" rather than the "roots rock rebel[lion]" that he had been hoping for.[4]

The song then moves away from the disappointing concert to address various other themes, nearly all relating to the state of the United Kingdom at the time. The song first gives an anti-violence message, then addresses the state of "wealth distribution" in the UK, promotes unity between black and white youths of the country before moving on to address the state of the British punk rock scene in 1978 which was becoming more mainstream.

Included is a jibe at unnamed groups who wear Burton suits. In an NME article at the time, Strummer said this was targeted at the power pop fad hyped by journalists as the next big thing in 1978. The lyric concludes that the new groups are in it only for money and fame.

The final lines fret over the social decline of Britain, noting sardonically that things were getting to the point where even Adolf Hitler could expect to be sent a limousine in the unlikely event of flying into London.[1]

The single was issued in June 1978 with four different colour sleeves – blue, green, yellow and pink.

This song was one of Joe Strummer's favourites. He continued to play it live with his new band The Mescaleros and it was played at his funeral.

The song is used in the 2017 film T2 Trainspotting.[5]

Rhyme scheme

The rhyme scheme is not consistent throughout. In order by verse, it is as follows (along with line-end words):

- 1. ABCB (man / Jamaica / Smart / operator)

- 2. ABAB (reggae / systems / say / listen)

- 3. AABB (night / right / treble / rebel)

- 3A ("inter-verse"). AA (back / attack)

- 4. ABAB (anywhere / guns / there / tons)

- 5. ABCB (youth / solution / Robin Hood / distribution)

- (Instrumental bridge between verses 5 and 6)

- 6. AABB (UK / anyway / fighting / lighting)

- 7. AABB (concerned / learned / funny / money)

- 8. AABB (votes / overcoats / today / anyway)

- 9. ABCB (wolf / sun / Palais / fun)

Personnel

"(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais"

- Joe Strummer – lead vocals, piano

- Mick Jones – backing vocals, lead guitar, harmonica

- Paul Simonon – bass guitar

- Topper Headon – drums

"The Prisoner"

- Mick Jones – lead vocals, lead guitar, rhythm guitar, acoustic guitar

- Joe Strummer – backing vocals, lead guitar, rhythm guitar

- Paul Simonon – bass guitar

- Topper Headon – drums

Critical reception

"(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" helped the Clash assert themselves as a more versatile band musically and politically than many of their peers, and it broke the exciting but limiting punk mould that had been established by the Sex Pistols; from now on the Clash would be "the thinking man's yobs".[6]

Robert Christgau recommended the single in his Consumer Guide published by The Village Voice on 4 September 1978, and described the song as "a must".[7] Denise Sullivan of AllMusic wrote that "(White Man) In Hammersmith Palais" "may have actually been the first song to merge punk and reggae."[3] Consequence of Sound described it as "one of Strummer’s greatest lyrical compositions".[8]

The song was ranked at No. 8 among the top "Tracks of the Year" for 1978 by NME.[9] In 2004, Rolling Stone rated the song as No. 430 in its list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[10] In December 2003, the British music magazine Uncut ranked the song No. 1 on their "The Clash's 30 best songs" list. The list was chosen by a panel including former band members Terry Chimes, Mick Jones, and Paul Simonon[11] In 2015, the Guardian ranked it No. 2 on Dave Simpson's "The Clash: 10 of the best" list,[12] and in 2020 it appeared in the number one position in Simpson's list of "The Clash's 40 greatest songs – ranked!"[13] Stereogum ranked it No. 4 on their "The 10 Best Clash Songs" list.[14]

Charts

| Charts (1978) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Singles (Official Charts Company)[15] | 32 |

Cover versions

Fighting Gravity covered the song on their 1999 live double album Hello Cleveland.[16] In that same year, 311 contributed their rendition of the song to the charity album Burning London: The Clash Tribute.[17]

Notes

- Begrand, Adrien. "100 FROM 1977 - 2003: The Best Songs Since Johnny Rotten Roared". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 24 August 2003. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Letts, Don (2001). The Clash: Westway to the World (Film). Sony Music Entertainment. Event occurs at 37:00. ASIN B000063UQN. ISBN 0-7389-0082-6. OCLC 49798077.

- Sullivan, Denise. (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais - The Clash at AllMusic. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Connor, Alan (30 March 2007). "White man's blues". BBC News. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Roffman, Michael (14 April 2017). "10 Songs by The Clash That Made Films Better". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- McCarthy, Jackie (22 December 1999). "White Riot". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Christgau, Robert (4 September 1978). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Partridge, Kenneth (10 April 2017). "How The Clash Can Lead to a Great Record Collection". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Albums and Tracks of the Year". NME. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 9 December 2004. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

361. Complete Control, The Clash

- "The Clash's 30 best songs". Uncut. 15 March 2015. p. 12. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

#1

- Simpson, Dave (23 September 2015). "The Clash: 10 of the best". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Simpson, Dave (9 January 2020). "The Clash's 40 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "The 10 Best Clash Songs". Stereogum. 7 December 2002. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

No. 4

- "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company.

- Fighting Gravity: (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais at AllMusic. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- 311: (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais at AllMusic. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

Further reading

- Gilbert, Pat (2005) [2004]. Passion Is a Fashion: The Real Story of The Clash (4th ed.). London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-84513-113-4. OCLC 61177239.

- Gray, Marcus (2005) [1995]. The Clash: Return of the Last Gang in Town (5th revised ed.). London: Helter Skelter. ISBN 1-905139-10-1. OCLC 60668626.

- Green, Johnny; Garry Barker (2003) [1997]. A Riot of Our Own: Night and Day with The Clash (3rd ed.). London: Orion. ISBN 0-7528-5843-2. OCLC 52990890.

- Gruen, Bob; Chris Salewicz (2004) [2001]. The Clash (3rd ed.). London: Omnibus. ISBN 1-903399-34-3. OCLC 69241279.

- Letts Don; Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, Topper Headon, Terry Chimes, Rick Elgood, The Clash (2001). The Clash, Westway to the World (Documentary). New York, NY: Sony Music Entertainment; Dorismo; Uptown Films. Event occurs at 37:00. ISBN 0-7389-0082-6. OCLC 49798077.

- Needs, Kris (25 January 2005). Joe Strummer and the Legend of the Clash. London: Plexus. ISBN 0-85965-348-X. OCLC 53155325.

- Topping, Keith (2004) [2003]. The Complete Clash (2nd ed.). Richmond: Reynolds & Hearn. ISBN 1-903111-70-6. OCLC 63129186.

External links

- Connor, Alan. (30 March 2007) White man's blues. SMASHED HITS Pop lyrics re-appraised by the Magazine. bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2008. "BBC article on the song and venue".

- Lyrics of this song at MetroLyrics

- Poster of the Hammersmith Palais gig referenced in song