Evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant that has leaves throughout the year and are always green. This is true even if the plant retains its foliage only in warm climates, and contrasts with deciduous plants, which completely lose their foliage during the winter or dry season

Evergreen species

There are many different kinds of evergreen plants, both trees and shrubs. Evergreens include:

- most species of conifers (e.g., pine, hemlock, blue spruce, and red cedar), but not all (e.g., larch)

- live oak, holly, and "ancient" gymnosperms such as cycads

- most angiosperms from frost-free climates, such as eucalypts and rainforest trees

- clubmosses and relatives

The Latin binomial term sempervirens, meaning "always green", refers to the evergreen nature of the plant, for instance

- Cupressus sempervirens (a cypress)

- Lonicera sempervirens (a honeysuckle)

- Sequoia sempervirens (a sequoia)

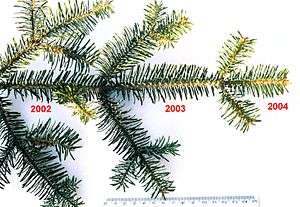

Leaf longevity in evergreen plants varies from a few months to several decades (over thirty years in the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine[1]).

Evergreen families

Japanese umbrella pine is unique in that it has its own family of which it is the only species.

Differences between evergreen and deciduous species

Evergreen and deciduous species vary in a range of morphological and physiological characters. Generally, broad-leaved evergreen species have thicker leaves than deciduous species, with a larger volume of parenchyma and air spaces per unit leaf area.[2] They have larger leaf biomass per unit leaf area, and hence a lower specific leaf area. Construction costs do not differ between the groups. Evergreens have generally a larger fraction of total plant biomass present as leaves (LMF),[3] but they often have a lower rate of photosynthesis.

Reasons for being evergreen or deciduous

Deciduous trees shed their leaves, usually as an adaptation to a cold or dry/wet season. Evergreen trees do lose leaves, but each tree loses its leaves gradually and not all at once. Most tropical rainforest plants are considered to be evergreens, replacing their leaves gradually throughout the year as the leaves age and fall, whereas species growing in seasonally arid climates may be either evergreen or deciduous. Most warm temperate climate plants are also evergreen. In cool temperate climates, fewer plants are evergreen, with a predominance of conifers, as few evergreen broadleaf plants can tolerate severe cold below about −26 °C (−15 °F).

In areas where there is a reason for being deciduous, e.g. a cold season or dry season, being evergreen is usually an adaptation to low nutrient levels. Deciduous trees lose nutrients whenever they lose their leaves. In warmer areas, species such as some pines and cypresses grow on poor soils and disturbed ground. In Rhododendron, a genus with many broadleaf evergreens, several species grow in mature forests but are usually found on highly acidic soil where the nutrients are less available to plants. In taiga or boreal forests, it is too cold for the organic matter in the soil to decay rapidly, so the nutrients in the soil are less easily available to plants, thus favouring evergreens.

In temperate climates, evergreens can reinforce their own survival; evergreen leaf and needle litter has a higher carbon-nitrogen ratio than deciduous leaf litter, contributing to a higher soil acidity and lower soil nitrogen content. These conditions favour the growth of more evergreens and make it more difficult for deciduous plants to persist. In addition, the shelter provided by existing evergreen plants can make it easier for younger evergreen plants to survive cold and/or drought.[4][5][6]

See also

- Semi-deciduous (semi-evergreen)

References

- Ewers, F. W. & Schmid, R. (1981). "Longevity of needle fascicles of Pinus longaeva (Bristlecone Pine) and other North American pines". Oecologia 51: 107–115

- Villar, Rafael; Ruiz-Robleto, Jeannete; Ubera, José Luis; Poorter, Hendrik (October 2013). "Exploring variation in leaf mass per area (LMA) from leaf to cell: An anatomical analysis of 26 woody species". American Journal of Botany. 100 (10): 1969–1980. doi:10.3732/ajb.1200562.

- Poorter, Hendrik; Jagodzinski, Andrzej M.; Ruiz-Peinado, Ricardo; Kuyah, Shem; Luo, Yunjian; Oleksyn, Jacek; Usoltsev, Vladimir A.; Buckley, Thomas N.; Reich, Peter B.; Sack, Lawren (2015). "How does biomass distribution change with size and differ among species? An analysis for 1200 plant species from five continents". New Phytologist. 208 (3): 736–749. doi:10.1111/nph.13571. PMC 5034769.

- Aerts, R. (1995). "The advantages of being evergreen". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 10 (10): 402–407.

- Matyssek, R. (1986) "Carbon, water and nitrogen relations in evergreen and deciduous conifers". Tree Physiology 2: 177–187.

- Sobrado, M. A. (1991) "Cost-Benefit Relationships in Deciduous and Evergreen Leaves of Tropical Dry Forest Species". Functional Ecology 5 (5): 608–616.

External links

- Helen Ingersoll (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.