55

9

When I pointed my GoDaddy domain name to the IP address of the GCP VM running my web server, this is all I had to do:

- Change GoDaddy nameservers to GCP nameservers

- Create A/CNAME/SOA entry in GCP DNS for my domain to my IP address

What prevents me from doing the same thing for any domain in the world?

As a matter of fact, I did:

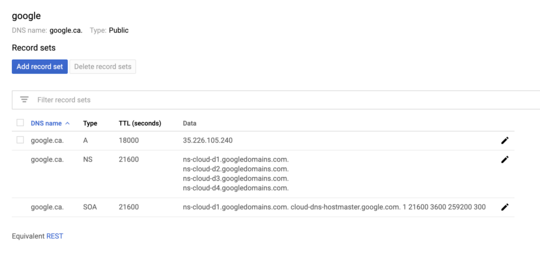

I created a CNAME, A, SOA entry for google.ca to my VMs external public IP address and nothing stopped me. Now I don't expect all of Google's traffic to start directing towards anywhere I want (that would be a fun DDOS), but what's going on here? What am I missing?

My intentions aren't unethical. I'm simply trying to learn how it all works.

2I don't use GoDaddy, but on my DNS host when it say something like

domain.something.that last dot is indicating it's still a subdomain of whatever domain I'm editing records for. Are you sure you're not actually making records forgoogle.ca.mydomain.com? – Logarr – 2020-02-13T15:52:16.04718

@Logarr Are you sure? Normally it is the other way around: Without the final dot domains are relative, with the final dot absolute domains are given.

– Marcel Krüger – 2020-02-13T18:58:25.2472Congratulations! You found a way break the internet. – Pablo – 2020-02-14T17:42:18.400

better to hide your public IP in the image – dev-masih – 2020-02-15T10:12:00.163

Oh, I found a big red button that looks scary. Let's try what it does! (No worries, just trying it was the right thing to do here. And quite interesting!) – Volker Siegel – 2020-02-16T03:39:50.287

1Don’t forget to accept one of the answers! If you need further clarification, please don’t hesitate to ask. – Daniel B – 2020-02-16T21:33:35.980