Referring to this Wikipedia example of an homograph attack, the URL of Wikipedia had the Latin characters A and E replaced with a similar Cyrillic copy (wikipediа.org). These characters look so similar, how can they be differentiated?

- 1,769

- 1

- 19

- 38

- 291

- 2

- 6

-

1How about « Defending against this attack » in the same Wikipedia article? – korrigan Mar 31 '18 at 16:19

-

@korrigan I was looking at the problem from a human-eye perspective. But nonetheless, the answer provided a simpler explanation than the version in wikipedia. Hence the approval. – toffee.beanns Mar 31 '18 at 16:22

-

2[Phish.AI IDN Protect](https://github.com/phishai/idn-protect-chrome) is a Chrome extension which alerts and possibly blocks IDN/Unicode websites mostly to prevent homograph attacks. – defalt Mar 31 '18 at 20:51

3 Answers

Browser vendors already try to protect you from homograph attacks by enforcing policies how IDNs (Internationalized Domain Names) should be displayed in the URL bar.

Their measures include blacklisting potentially confusable symbols (e.g. ֊, the "Armenian hyphen" U+058A) and displaying URLs with characters from non-latin alphabets as Punycode under certain conditions. So, if you visit

https://wikipediа.org

the URL will be displayed in your URL bar as

https://xn--wikipedi-86g.org/

following the Punycode conversion rules, which you can easily distinguish from wikipedia.org.

If you're interested in the specific algorithm your browser uses to display IDNs, see:

However, converting bad IDNs while maintaining usability (e.g. you'd still want to display a literal ä to someone in Germany) has turned out to be somewhat elusive which is why even in 2018 new attacks have come up.

If you don't trust your browser's built-in protection, there is also a browser extension available which warns you about IDN domains (as @defalt points out). Or you can choose a manual way of detection, as @wchargin describes in his answer.

- 43,922

- 13

- 140

- 136

Arminius's answer mentions the conditions in which browsers render punycode instead of the actual Unicode glyphs. In my experience, these conditions are not sufficient: for instance, the URL https://аррӏе.com/ (link is safe, but could be a phishing site!) is rendered as punycode by Chrome but not by Firefox:

Here is the solution that I personally use. It may be overkill, but it protects against exactly this attack.

It is a prerequisite for this solution that, whenver you are about to enter any credentials into any web site, you always read the address bar before entering any data.* You should be doing this anyway!—but it is actually necessary for what follows.

My procedure is simple. Before entering credentials, I copy the text in the address bar, then launch the program hexob, which I have defined as follows (in a file ~/bin/hexob):

#!/bin/sh

xsel -ob | xxd | xmessage -file -

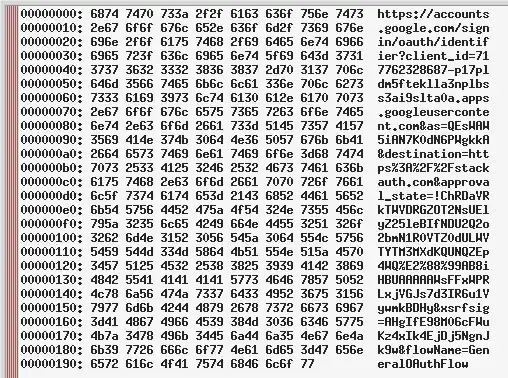

This program displays the code units for the UTF-8 encoding of the clipboard in a message box, like this:

I can quickly verify by reading the host that this is a valid login URL: because the host appears correctly on the right-hand side, all code points of the host are in ASCII.

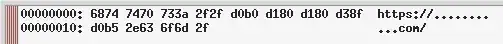

On the other hand, if someone had linked me to https://аррӏе.com/, which exemplifies a homograph attack, then the message box would appear like this:

Here, I see the code units for the UTF-8 encoding of https://аррӏе.com/, which is very different from the UTF-8 encoding of https://apple.com/. Most of the code points are not in ASCII, so their UTF-8 code units have the MSB set, and therefore they appear as just some number of .s on the right-hand side. If I see .s on the right-hand side in the host part of the URL, I stop and do not enter any credentials.

I type C-l C-c Super-p hexob RET to complete this whole process, which takes just a few seconds. (My Super-p might be your Alt-F2 or similar.)

* Note that you must do this every time that you are about to enter data. For instance, if you're logging into Google and you enter your password, then Google says "password incorrect", you must execute this procedure again. This is because Google's login page has an open redirect: I can make a page that directs you to Google's actual login system, and, after you log in, automatically redirects you to my phishing page that looks exactly like Google's login system but is controlled by me.

- 293

- 2

- 8

-

-

I think a simpler way would be to hash the contents of the clipboard then compare against the hash of what you expect the URL to be – Prime Mar 31 '18 at 22:43

-

1@Prime: I don't think that that's simpler at all. That requires me to know what I expect the URL to be—so now instead of just copying the URL, I have to additionally type in the whole `https://login.mylongdomain.com`? And if it doesn't match exactly, it just says "hash failure"—which is far more likely to be from a typo than a homograph attack, making me (the user) frustrated and more likely to just say "eh, it's probably safe anyway"? Plus, if you have the expected value, there's no reason to hash at all—just compare the two URLs and show a useful diff! – wchargin Mar 31 '18 at 23:16

-

3@Prime: The #1 concern here is usability. If the thing takes more than five seconds or more than zero brainpower to execute, then it has sufficient friction that I'm not going to be inclined to use the solution. As they say, "security at the expense of usability comes at the expense of security"! – wchargin Mar 31 '18 at 23:17

-

1this could be re-implemented as a *bookmarklet* that pops up a dialog showing the composition of the domain part of document.location – Jasen Apr 01 '18 at 05:13

-

2@Jasen: Yep, it sure could—but note that `window.alert` can be modified by the attacker in case the page is phished! I suspect that a browser extension would be able to do the job more robustly, but I'm not familiar with how those are implemented, so I can't say for sure. Personally, I like separating the verification from the attack surface as much as possible, which means no JS for me. But this solution is inherently homegrown, so chacun à son goût. :-) – wchargin Apr 01 '18 at 05:24

-

As always, I'd be interested to hear from the two people who downvoted this answer. :-) – wchargin Apr 01 '18 at 20:25

-

Another thing not mentioned in the other answers: besides its other benefits, a password manager will help you protect against those attacks: your credentials saved for www.google.com will not be filled in automatically on www.googIe.com (the second-to-last character is an uppercase I), hinting to the fact that something is off. You need to copy-and-paste the password manually and explicitly to log onto that site.

- 829

- 9

- 15