Water powered car

"Water powered" cars are a recurrent theme amongst free energy advocates. The appeal of the idea is rooted in the fact that water is much more common than, and usually[2] cheaper than, oil, especially during an energy crisis.

| Style over substance Pseudoscience |

| Popular pseudosciences |

| Random examples |

v - t - e |

“”There is no gas shortage, man. It's all fake. The oil companies control everything. Like, there is this guy that invented this car and it runs on water, man. It's got a fiberglass air-cooled engine and it runs on water. |

| —Steven Hyde, a character in the That '70s Show[1] |

In one variant of the idea, some magical substance is added to water, making it combustible and turning it into a fuel that can be fed to an internal combustion engine. In another, the "fuel" is often referred to as HHO Water (not to be confused with dihydrogen monoxide). In the purported generators, water is apparently changed into "HHO gas", electrons from which can be used to make cars run. Sometimes, it's claimed that hydrogen gas is produced — thus making use of existing hydrogen fuel cells.[3]

Genepax

One particular example is the Genepax car, revealed in Japan in 2008. While quite tight-lipped about specific processes, Genepax hinted that the car worked along similar lines to metal hydride reactions that produce hydrogen. Once this hydrogen was produced, it could be consumed in the same manner as working hydrogen fuel cells. However, with a metal hydride reactant being consumed in the process, the "fuel" component certainly wouldn't be water. Depending on the specific chemical reaction used, it may have been less efficient than other methods of hydrogen generation, and less environmentally friendly than even fossil fuel reactions. Genepax ceased trading and production in 2009, probably in case they were called out on their scam. The website, however, is still available.[4]

Stanley Meyer

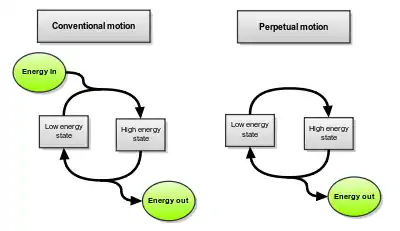

The water fuel cell claimed by Stanley Meyer appeared in the 1990s and involved modifying existing combustion engines to take fuel directly. Meyer's supposed mechanism involved utilising hydrogen-oxygen reactions to power the engine and consumed electricity (in his "fuel cell") to split water into these components — overlapping it with the concept of the perpetual motion machine, as mentioned by Phillip Ball writing in the journal Nature.[6] Meyer was convicted of fraud in 1996 over the claims made in his patents, and died of an aneurysm in 1998. True Believers exploited his death as evidence of a free energy suppression conspiracy theory involving oil companies. PESWiki, for example, doesn't even refer to it as a conspiracy theory, simply saying that his death is "mysterious," and due to poisoning.[7]

The apparent perpetual motion issue with Meyer's technology is avoided with a handwave known as "frequency enhanced electrolysis."[8] This is essentially claiming to re-write basic laws of science and chemistry, such as Faraday's Law of electrolysis and conservation of energy, by claiming that boosts in efficiency will solve the problem. Now, it is true that the efficiency of physical processes can improve with resonant frequencies. Gravity, for example, exhibits resonance effects when the orbital periods of planets begin to coincide; nuclear magnetic resonance uses resonant frequencies to tilt the magnetic moments of atomic nuclei, despite the resistance to such a tilt by the very-high-power applied magnetic field. Resonant processes are very real physical phenomena, but they do not violate conservation of energy in the same way that any water-powered system must do. Resonance is only a method of increasing efficiency of a process from close to 0% to close to 100% — any perpetual motion machine based around using water must go well above 100% to be useful.

Description

Water is an extremely thermodynamically stable molecule, hence its abundance on Earth and the fact that it is the product of many oxidation reactions, including the burning of hydrocarbon fuels. As a result of this, energy must be put into the water molecule to break it up and produce a hydrogen-oxygen mix, just over 280 kJ/mol.[9] To put this value in perspective, converting a litre of water into hydrogen and oxygen would require approximately the same amount of energy as the recommended daily calorie intake (~2500 kCal) of an adult human. Conversely, burning enough hydrogen and oxygen to form a litre of water would release this much energy.

It is true that hydrogen gas will react with oxygen to produce energy, and that the only product of this reaction is water. This is the principle of a fuel cell. So you do get this energy back, but you cannot just magically get this from water without putting energy in first. The energy that needs to be put in to generate hydrogen and oxygen, due to the laws of microscopic reversibility and thermodynamics, is exactly the same as the energy that is produced by the hydrogen and oxygen reaction.

The popularity of the water power scam may be due to the misconception that hydrogen is some form of fuel, when really it's a form of short-term energy storage. Hydrogen fuel cell cars can only be powered by hydrogen if water is first broken into a hydrogen/oxygen mixture — the energy required to achieve this is the theoretical maximum that can be obtained from the fuel cell. As we don't find hydrogen lying around naturally on the Earth's surface (the presence of oxygen sees to that), we can't mine it as a fuel in the same way we do with fossil fuels. We ourselves must put that energy in by some means — preferably through renewable energy. In the Genepax example above, it is suspected that a metal hydride was consumed in the reaction to produce hydrogen from water, hence it would just be transforming energy from one unstable chemical (a metal hydride) to another (hydrogen gas), before burning that to produce water. This isn't particularly miraculous chemistry; many reactive substances will split water into hydrogen and oxygen (magnesium, potassium to name two). But, as these metals don't exist in their pure form in nature and need to be processed first, we have to put energy into forming them before they can release that energy to form hydrogen, before we can burn that to get the energy back.

An analogy can be made that this is like burning a large amount of oil in a conventional power station, to produce the electricity needed to run equipment that produces "artificial" long chain alkane molecules in a lab, then burning those and calling it a miraculous and environmentally friendly process — in other words, total bullshit.

It's certainly possible to run a car on water, by electrolyzing it and then burning the hydrogen produced; the only problem is you'll need a second, bigger engine to supply power to the electrolyzer, unless you use solar panels or some other renewable source to electrolyze the water separately and somehow collect and compress the hydrogen into tanks. Fusion of the hydrogen isotopes present in water could hypothetically provide energy, but even if fusion was common, the miniaturization necessary to install a fusion reactor in a car would probably not be developed while cars were still used.

Don't miss

"Like Water for Octane"[10], an episode of The Lone Gunmen, a spinoff of The X-Files that ran for only one season in 2001. The plot involves the titular protagonists, a group of conspiracy theorists, searching for a water-powered car that was allegedly suppressed by the oil companies, with shadowy figures pursuing them as they get closer to the truth. Said truth: the car's inventor destroyed it himself upon realizing all the hidden environmental costs of it, particularly how it would fuel suburban sprawl and consumerism just as cheap gasoline did back in the 1950s. The energy company executives weren't looking for the car's blueprints to shred them, but rather, to hand them over to Detroit in order to keep the consumerist gravy train going even after peak oil.

See also

- Dihydrogen monoxide (dangerous, even if it's used as a fuel)

- Hydrogen economy, a somewhat plausible idea where cars produce water

External links

- Simple Water Fuel - You can play "spot the scam cliché" with this website.

- Gas Millage Hoaxes

- "It runs on water man…" - Memorable skit from That 70's Show.

References

- That '70s Show (1998–2006): Quotes IMDb.

- Oil is cheaper than milk and water by Mark Melin (Jan. 20, 2016, 8:26 AM) Business Insider.

- Just add H20 to go? Chinese firm claims its hydrogen-powered car can travel 500km fuelled by water by Laurie Chen (7:55pm, 26 May, 2019) South China Morning Post.

- Genepax.com

- Process and apparatus for the production of fuel gas and the enhanced release of thermal energy from such gas U.S. Patent 5,149,407.

- Nature — Burning water and other myths

- PESWiki — Stanley Meyer

- Eric Hansen's Water Fuel Hydroxy Manifesto

- Hyperphysics — Electrolysis of water

- The X-Files Wiki: "Like Water for Octane"