Two-round voting

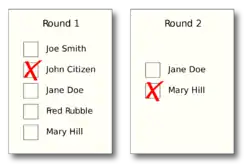

Two-round voting is sort of self-descriptive. The two-round system is a single-member system, usually first past the post, under which the first round of voting includes all the candidates, while the second round only includes the two winners of the first round. One example of this is France. Like IRV, it was created to deal with some of the issues of first past the post. It is mostly seen to elect "presidential" figures down to and including the mayoral level. While it does address some of the downsides of FPTP, it fails to address others and creates some unique downsides of its own. A somewhat related but different method is employed to select hosts for the Olympic Games or the Soccer World Cup in which the weakest vote getter is eliminated after every round until a predetermined majority is reached. This multiple round election system is arguably "fairer" and ensures no option is "prematurely" discarded but it presupposes the willingness and ability to hold multiple rounds of elections in short succession and is thus only practicable in small voting bodies rather than general electoral populaces.

| How the sausage is made Politics |

| Theory |

| Practice |

| Philosophies |

| Terms |

| As usual |

| Country sections |

|

v - t - e |

Downsides of FPTP it addresses

- In FPTP less than 50% of the vote can be enough to win the seat of a constituency, producing a representative that the majority of his constituents did not vote for - this cannot happen with Two Round Voting

- In FPTP a party that has a similar political profile to an existing party will actually hurt the chances of a politician of those views getting elected by splitting the vote ("spoiler effect"). In TRV, people can vote for e.g. the "extremely left wing party" in the first round and then support their "lesser of two evils" choice the "slightly left of center party" in the second round against the "extremely right wing party". However, as the French Presidential Election 2002 showed, this only works when it is virtually clear who will make it to the runoff, which raises the question what the point of the first round is.

- A "protest" or "lost" vote is "safer" as - unless any candidate wins 50% in the first round - there is always the possibility to "correct" it in the second round

New downsides it creates compared to FPTP and other methods of voting

- In a very fractured electorate, the candidates that make it to the runoff can have a relatively low share of the vote, producing tactical or even disgusted "holding your nose" voting in the second round as arguably seen in both the 2002 and 2017 French Presidential elections

- Having two separate elections in almost all cases can depress turnout (especially for people who have to skip work to go voting) and especially the first round is often taken less seriously

- Say Party A received 35%, Party B 40% and Party C 15% - in the time between the announcement of the election and the runoff, there will be heavy attempts to convince either the candidate of Party C or its voters to switch allegiance (as the C votes would be enough to give either candidate the win) arguably giving Party C outsize influence. This may be a feature rather than a bug, though, if you think minority views should be taken into account

- It is arguably a more complicated system and arguably produces a more fractured political system (consider the number of relevant political parties in the UK or the US that both operate with FPTP compared to those in France or mayoral politics in Germany that both operate with TRV)

- In FPTP there is always a candidate or party for every voter to vote for, provided the bar to enter oneself as a candidate is not so high as to make it impractical. While most of those votes are "lost", they are at least possible and potentially send a signal. In TRV this is only possible in the first round and in the second round candidates that did not receive the backing of a significant minority or even the majority of the electorate are the only choice the electorate has.

Downsides of FPTP it does not address

- FPTP can produce widely skewed results in terms of seats compared to the popular vote. While a popular vote becomes a bit harder to calculate with two rounds involved, it can still widely distort the result

- Like with FPTP a fringe party with a strong local base of support (say, a party advocating separatism of a certain region) will have outsize representation compared to a small party with more equally distributed support. Let's say 5% across the country support a certain measure, but 50% in twenty constituencies collectively representing 2% of the population oppose it. Under proportional representation one could expect the "for" side to gain 5% of seats while the "against" side might get one percent of seats or none, depending on the details of allocation. In both FPTP and TRV, the "for" side would get not a single seat whereas the "against" side would have good chances at 20 seats.

You can help RationalWiki by expanding it.